In May and early June, there was a spate of tasting competitions held in and out of Japan, many of which are significant in both scale, and potential impact. These competitions have usually hundreds of sake that are blindly judged by dozens of judges, and the results are made public. This happens across several media, both electronic and printed, and several of the organizations provide stickers for the producers to further promote the winning sake.

While such results are not the only way to select sake, and in fact are arguably not even close to the best way, these contests do an outstanding job of at least one thing: they draw attention to sake as a super-premium beverage worthy of assessing at the highest level by experienced professionals.

Let us look at four such contests (in the chronological order in which they took place), with a bit of information about each, and links to the results as well.

“The Nationals” in Japan

In May, the sake industry held the 106th (!) running of the Zenkoku Shinshu Kampyoukai, or “National New Sake Tasting Competition,” which has the official English translation of the “Japan Sake Awards.” While my unofficial translation above is certainly more descriptive, the nature of the contest should be clear.

Interestingly, at 106, it is the longest running competition of its kind anywhere in the world. For all but the last few of those it was run by the government itself with the goal having always been helping brewers improve their skills. The last few years, the body running it has been semi-privatized.

Those interested can find more information in the archives of this newsletter (which go back to 1999!), in particular in the June or July editions for each year.

The sake submitted to this contest by the brewers is not stuff you can normally buy, but rather daiginjo or junmai daiginjo made specifically for this contest. It is brewed to have a minimum of faults, but still seem unique and special. I often refer to it as “daiginjo on steroids.”

Just about two-thirds of Japan’s sakagura submitted an entry to the contest, for a total of 850 entries. Each company is allowed to submit one sake per brewing license, i.e. one per brewing facility owned. Some larger companies own more than one facility so they would be permitted one for each.

Almost all of it is not junmai because using the added-alcohol step brings out more aromas and flavors. But this year, 163 of the 850 submissions were junmai, up seven submissions from a year ago. It seems that at least a few more brewers are interested in trying to win with junmai sake.

Sake is tasted blind in round one, and about half make it to round two. They are then tasted blind again, and about half of these will be designated as gold, the rest that made it into the second round are designated as prize-winners (the term “silver” is not used, although the gist is the same).

While the contest is extremely prestigious within the sake industry, it is not that commonly used in marketing as the average consumer has no idea this contest even exists.

For the eighth time in twelve years, and sixth in a row, Fukushima Prefecture won more golds than any other prefecture. This was a new record, as no prefecture has ever won the most golds for six years in a row. Just as interestingly, Hyogo Prefecture (wherein sits Nada, the Mecca of sake brewing) was number two. As has been the case for the past decade, the entire Tohoku region did very, very well.

While the sake submitted is not usually sake destined for the market, the flavors, aromas, styles and leading prefectures are a harbinger of where sake is currently headed. Therein lies the contest’s appeal.

There is so much to be said about this competition: the changes over the years, the politics, the history, the records, and more. Much of that can be dug up in the archives of this newsletter, but more importantly it seems as though amidst today’s sake popularity, more brewers and consumers as well are showing an interest in this historically and culturally significant competition.

You can see the results in Japanese here and in English here.

IWC in Japan

From May 13th to May 16th, the 10th International Wine Challenge 2018 Sake Competition was held in Yamagata Prefecture. This was the third time the event was held in Japan, away from its usual home of London.

From May 13th to May 16th, the 10th International Wine Challenge 2018 Sake Competition was held in Yamagata Prefecture. This was the third time the event was held in Japan, away from its usual home of London.

This contest sees sake judged in panels, with discussion amongst the judges to ensure general consensus. It is a great way to help raise more experienced sake judges all over the world. Also, the results are marketed wonderfully and glamorously, furthering sake promotion efforts.

Sake is judged in one of nine categories: futsuu-shu (regular sake, i.e. non-premium sake), honjozo-shu, junmai-shu, ginjo-shu, junmai ginjo-shu, daiginjo-shu, junmai daiginjo-shu, koshu (aged sake) and sparkling sake. That is a lot of tasting, and it took us three and a half days to work through it all in the multiple rounds that were called for. Judges are encouraged to judge a sake as a representative of the grade in which it was submitted, meaning it cannot be overly ostentatious if not of a grade that is expected to demonstrate that. (In other words, super fruity honjozo, for example, would get dinged for that character.)

Gold, Silver, and Bronze medals are awarded, with sake that is good but not quite of medal quality receiving a Commended award. Producers that choose to can affix little labels to their bottles advertising those accolades.

Complete results in Japanese can be found here: http://www.sakesamurai.jp/iwc18_medal.html

The list of all medal winners and commended sake can be found in English here : www.internationalwinechallenge.com/canopy/search.php#tabs1-sake. If you click on “Search for a Sake” the entire list of Medal and Commended sake comes up, in alphabetical order.

Also, the trophy winners (only; not all medal winners) for each category are here in English (near the bottom of the page – because the best is saved for last!): https://www.internationalwinechallenge.com/trophy-results-2018.html

Hasegawa Saketen “Sake Competition”

Next – at least chronologically – is the Hasegawa Saketen “Sake Competiton.” Hasegawa Saketen is a large and well known sake distributor and retailer in Japan that has for ten years or so ran a sake competition of its own. The sake submitted is all market sake – nothing specially brewed. And the judges are industry people – brewers, toji, owners, and folks like myself. There are two rounds held two days apart.

Next – at least chronologically – is the Hasegawa Saketen “Sake Competiton.” Hasegawa Saketen is a large and well known sake distributor and retailer in Japan that has for ten years or so ran a sake competition of its own. The sake submitted is all market sake – nothing specially brewed. And the judges are industry people – brewers, toji, owners, and folks like myself. There are two rounds held two days apart.

Just like the Japan Sake Awards mentioned above, each judge assesses alone, with no input or influence permitted, and no discussion amongst judges either.

This year, it was held right after the IWC mentioned above. That was challenging. Furthermore, in the second round there are over 500 sake to be tasted – by each judge – in one day. It’s a marathon.

Yet, at the same time, the contest is on the up-and-up, and worthwhile to participate in, and the results are useful as well. Interestingly, the same sake seem to be popping up at the top each year, with a few changing in and out. And these are mostly well known, prized sake. The results of the blind-tasting contest, then, seem to uphold the popularity of those sake.

The gold medal results in English are here: https://sakecompetition.com/?page_id=1647 Poking around the English header will lead to more about the contest, and also, there is plenty about the competition on that site in Japanese as well.

US National Sake Appraisal

Last but by no means least is the 2018 US National Sake Appraisal, held in June this year (although usually it is held in August). This contest takes place in Hawaii with a mix of judges, some from Japan and some from the US and other countries. The judges from Japan are from the National Research Institute of Brewing, and various prefectures around Japan. All are quite esteemed.

Last but by no means least is the 2018 US National Sake Appraisal, held in June this year (although usually it is held in August). This contest takes place in Hawaii with a mix of judges, some from Japan and some from the US and other countries. The judges from Japan are from the National Research Institute of Brewing, and various prefectures around Japan. All are quite esteemed.

This judging too takes place just as it does in the Japan Sake Awards; in other words, each judge tastes on his or her own, with no discussion. Results are tallied as an average of all judges’ scores.

The classifications for judging are a bit different, and are more focused on the milling rate than whether or not they are junmai style or not. So Junmai is one grouping, Jumai Ginjo and (non-junmai, i.e. added alcohol) ginjo are together as another group, Daiginjo A – in which the milling is 40% or less (i.e. 35%, 38%), and Daiginjo B for which the milling is between 50% and 40%. This is certainly a slightly different take, and a very valid one for sure.

These sake are then taken on a road show, being presented at the Joy of Sake events which this year are to be held in New York (just finished!), Honolulu in July, London in September and Tokyo in November. If you are anywhere near one of these cities at those times, be sure to check the party out. The results have been made public, and you can see the top winner in each category, and the medal winners for each as well here: http://www.sakeappraisal.org/en/appraisal-2018.html

~~~

There are other competitions too, and there will be more popping up. Of this I am quite sure. These are just the most visible. The results are extremely interesting, and if you want to make things even more interesting, take the time to look across the results of each of the above and see what names keep popping up; that tells us a lot. I’m just sayin’.

After having judged in three out of these four this year, and all of them at one time or another, there are a couple of thoughts about these competitions.

First and foremost, they all attract attention to quality sake, and the fact that sake is worthy of being assessed by beverage professionals from around the world. This is an unequivocally good thing!

In truth, though, only certain styles or types of sake will do well through. Those that do are, of course, worthy and deserving for sure. But in these contests, sake is tasted on its own, with no food, no friends, no ambiance suffusing the situation. Sake that has any semblance of quirky or idiosyncratic character will not likely win a medal in any of these. Often, such characteristics can be extremely appealing. But sake that is not a part of the orthodox clean light ginjo borg does not have much of a chance. And it is what it is.

In the end, it’s a good tradeoff. The sake that receive awards are all great sake, and the contests draw attention to sake. That’s enough, at least for now, methinks.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

No Sake Stone Remains Left Unturned!

From Monday August 13 to Wednesday August 15, 2018, I will hold the 30th North American running of the Sake Professional Course at at the Miami Culinary Institute in Miami, Florida. The course will run 9-5 all three days. The cost for the course, all materials, and the right to take the exam for Certified Sake Professional certification is $899. Learn more here. Interested? Please email me at sakeguy@gol.com .

Last month in this newsletter we talked about aged sake, and pointed out that, although it is not quite mainstream, matured sake, known as koshu or chouki jukusei-shu, can be extremely interesting. And that is one reason the Nippon Jozo Kyokai, i.e. the Brewing Society of Japan introduced above (BSJ), a while ago began the One-Hundred Year Aged Sake Project.

Last month in this newsletter we talked about aged sake, and pointed out that, although it is not quite mainstream, matured sake, known as koshu or chouki jukusei-shu, can be extremely interesting. And that is one reason the Nippon Jozo Kyokai, i.e. the Brewing Society of Japan introduced above (BSJ), a while ago began the One-Hundred Year Aged Sake Project. there will sit on wooden (hinoki, like cypress) shelves with no metal anywhere near them. The rest, stored at Nodai, will be handled by placing the bottles inside metal tanks. Temperatures will be maintained between 15C and 20C.

there will sit on wooden (hinoki, like cypress) shelves with no metal anywhere near them. The rest, stored at Nodai, will be handled by placing the bottles inside metal tanks. Temperatures will be maintained between 15C and 20C. Along with the one bottle of sake destined to sit a full century, each kura submitted ten smaller bottles (720 ml) to be used at ten along-the-way tastings to be held every ten years. The first of those tastings was held this past November, exactly ten years since it all was laid down. I was fortunate enough to be invited to that tasting, and even if only for the uniqueness of it, the event was fascinating.

Along with the one bottle of sake destined to sit a full century, each kura submitted ten smaller bottles (720 ml) to be used at ten along-the-way tastings to be held every ten years. The first of those tastings was held this past November, exactly ten years since it all was laid down. I was fortunate enough to be invited to that tasting, and even if only for the uniqueness of it, the event was fascinating. Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Next Five was formed in 2010, and is a group of five brewers in Akita Prefecture whose stated objective is to discover what sake of the next generation will be, and to be leaders going into that. They do a number of promotional activities, focusing mainly on three things: sake tasting events, other social and artistic events around which sake can be enjoyed, and all gathering each year at one of the five breweries and working together to make one sake together, with each one of them taking on one of the indispensable roles in sake brewing each time. I have also read that their plan was to have each member step down as they get older and replace them with like-minded younger brewers so as to keep the spirit of the next generation alive, although I am not sure if that has actually taken place. From my perspective they are the most visible, at least until recently.

Next Five was formed in 2010, and is a group of five brewers in Akita Prefecture whose stated objective is to discover what sake of the next generation will be, and to be leaders going into that. They do a number of promotional activities, focusing mainly on three things: sake tasting events, other social and artistic events around which sake can be enjoyed, and all gathering each year at one of the five breweries and working together to make one sake together, with each one of them taking on one of the indispensable roles in sake brewing each time. I have also read that their plan was to have each member step down as they get older and replace them with like-minded younger brewers so as to keep the spirit of the next generation alive, although I am not sure if that has actually taken place. From my perspective they are the most visible, at least until recently. Finally things are beginning to cool down as we move through nature’s most endearing season. Along with the rapidly turning leaves, cooler breezes, and better food, autumn is the traditional time when sake brewed the previous season goes on sale. Two types of sake you may come across in your autumnal perusing are aki-agari and hiya-oroshi.

Finally things are beginning to cool down as we move through nature’s most endearing season. Along with the rapidly turning leaves, cooler breezes, and better food, autumn is the traditional time when sake brewed the previous season goes on sale. Two types of sake you may come across in your autumnal perusing are aki-agari and hiya-oroshi. releasing hiya-oroshi, September 9. Naturally, this is not law, but just something the brewers have mutually agreed upon to add a bit of specialness to the event and the sake that it highlights.

releasing hiya-oroshi, September 9. Naturally, this is not law, but just something the brewers have mutually agreed upon to add a bit of specialness to the event and the sake that it highlights. And to make things interesting, some brewers consider hiya-oroshi as just one kind of aki-agari. In truth, that is actually valid thanks to the vagueness of the definition of aki-agari, even if it is a tad confusing. So have fun with that.

And to make things interesting, some brewers consider hiya-oroshi as just one kind of aki-agari. In truth, that is actually valid thanks to the vagueness of the definition of aki-agari, even if it is a tad confusing. So have fun with that.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me. bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable.

bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable. Kijoushu

Kijoushu

Several years ago, in July of 2014, the Yamagata Prefecture Sake Brewers’ Association began the process of securing a designation of their sake as a Geographical Indication recognized by the World Trade Organization and various international treaties. In order to qualify for something like this, a product (any product applying for a GI) must possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin. Securing such a designation gives the region and its producers the exclusive right to an appropriate indication on the label.

Several years ago, in July of 2014, the Yamagata Prefecture Sake Brewers’ Association began the process of securing a designation of their sake as a Geographical Indication recognized by the World Trade Organization and various international treaties. In order to qualify for something like this, a product (any product applying for a GI) must possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin. Securing such a designation gives the region and its producers the exclusive right to an appropriate indication on the label. public hearing on the topic on October 19 of this year. It was not made clear how long this stage will take, but assuming it does pass smoothly, Yamagata Sake will come into existence as a bona fide Geographical Indication (GI) for sake. One more region in Japan, the city of Hakusan in Ishikawa Prefecture, has qualified for a GI for the sake of that region. However, it only applies to the five breweries in city of Hakusan; the rest of the breweries in Ishikawa Prefecture are unaffected. Yamagata Prefecture will be the first entire prefecture to secure this distinction.

public hearing on the topic on October 19 of this year. It was not made clear how long this stage will take, but assuming it does pass smoothly, Yamagata Sake will come into existence as a bona fide Geographical Indication (GI) for sake. One more region in Japan, the city of Hakusan in Ishikawa Prefecture, has qualified for a GI for the sake of that region. However, it only applies to the five breweries in city of Hakusan; the rest of the breweries in Ishikawa Prefecture are unaffected. Yamagata Prefecture will be the first entire prefecture to secure this distinction. There are at present 51 sakagura brewing in Yamagata. The oldest of these dates back to the Japanese “Warring States” era of long civil war, while the youngest can trace their roots to the beginning of the Edo period. Even the new kid in town is an old and dignified character.

There are at present 51 sakagura brewing in Yamagata. The oldest of these dates back to the Japanese “Warring States” era of long civil war, while the youngest can trace their roots to the beginning of the Edo period. Even the new kid in town is an old and dignified character. From Monday, April 3 until Wednesday April 5, I will hold the first Sake Professional Course of 2017 at Bentley Reserve in San Francisco. If interested, for more information please send me an email at sakeguy@gol.com.

From Monday, April 3 until Wednesday April 5, I will hold the first Sake Professional Course of 2017 at Bentley Reserve in San Francisco. If interested, for more information please send me an email at sakeguy@gol.com. In the April issue of blog, archived

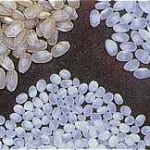

In the April issue of blog, archived  Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors.

Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors. But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop.

But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop. Still, as mentioned above, sake rice production was on the decline. Compared to the easy to sell table rice, sake rice was hard to grow, it is quite tall and therefore falls over easily, and yields per field are much lower. It therefore costs farmers more to grow it, and there is less of a market for it. So in order to secure the high quality sake rice they needed, the brewers of Nada (modern day Kobe and Nishinomiya cities in the same prefecture, Hyogo, where the largest breweries have been for 250 years) created a contractual system with the farmers in the region (then known as the Harima region, now just a part of Hyogo) to secure a stable supply at a price that made it worth it to the farming community.

Still, as mentioned above, sake rice production was on the decline. Compared to the easy to sell table rice, sake rice was hard to grow, it is quite tall and therefore falls over easily, and yields per field are much lower. It therefore costs farmers more to grow it, and there is less of a market for it. So in order to secure the high quality sake rice they needed, the brewers of Nada (modern day Kobe and Nishinomiya cities in the same prefecture, Hyogo, where the largest breweries have been for 250 years) created a contractual system with the farmers in the region (then known as the Harima region, now just a part of Hyogo) to secure a stable supply at a price that made it worth it to the farming community. These are then grown to yield more seeds, which are then grown to yield even more seeds, that are then distributed to seed cooperatives, who then distribute the seeds to the farmers to use to grow the rice. So count ‘em: that is only three generations from purity each year, no seeds are any more than three generations from individually inspected and assessed purity. Dig that.

These are then grown to yield more seeds, which are then grown to yield even more seeds, that are then distributed to seed cooperatives, who then distribute the seeds to the farmers to use to grow the rice. So count ‘em: that is only three generations from purity each year, no seeds are any more than three generations from individually inspected and assessed purity. Dig that. More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available

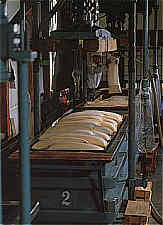

More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available  Milling

Milling Machine press

Machine press Fune (box press)

Fune (box press) Shizuku

Shizuku Pasteurization

Pasteurization Aging

Aging Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more

Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more