Sakamai or Rice Variety

There are several types of rice used to make Japanese sake, and each type yields specific flavor profiles. Keep in mind that these nine types of rice are only part of the battle. How sake is brewed and the water used are the other parts of the story. Further, there is a massive range of styles and tremendous overlap across the board. Finally, the degree of rice milling plays a major role in the final product.

There are several types of rice used to make Japanese sake, and each type yields specific flavor profiles. Keep in mind that these nine types of rice are only part of the battle. How sake is brewed and the water used are the other parts of the story. Further, there is a massive range of styles and tremendous overlap across the board. Finally, the degree of rice milling plays a major role in the final product.

1. Yamada Nishiki Rice

From Hyogo, Okayama and Fukuoka. The so-called King of Sake Rice. Fragrant, well-blended soft flavor. Representative Sake Brands: About any daiginjo in the country (slight exaggeration). Hard to give one good recommendation. Nadagiku, Tatsuriki, Okuharima (all Hyogo) and Ginban (Toyama) are good examples.

2. Omachi Rice

From Okayama. Generally less fragrant, more defined flavor elements, more earthiness. The only pure strain of rice left in Japan (to my knowledge, so don’ argue for this point should you choose to quote me). Representative Sake Brands: Bizen Sake no Hitosuji (Okayama). Most visible users of Omachi. Use it across a whole range of sake types . Lots of it good warmed. Some fermented in Bizen-yaki tanks. Also look for Yorokobi no Izumi form Okayama.

3. Miyama Nishiki Rice

From Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Miyagi, Fukushima, and Nagano. Slightly less dry sake, more rice-like flavor, more mouth feel, and quiet nose. Representative Sake Brands: Sharaku (Fukushima), Hamachidori (Iwate). Both sake have great mouth/tongue feel and presence.

4. Gohyakumangoku Rice

From Niigata, Fukushima, Toyama, and Ishikawa. Smooth and clean and dry and slightly fragrant. Representative Sake Brands: Shimeharitsuru and Kubota, or just about anything from Niigata.

5. Oseto Rice

From Kagawa. Rich and earthy, very distinctive. Representative Sake Brands: Ayakiku (Kagawa). They use only Oseto rice here, in all their sake.

6. Hatta Nishiki Rice

From Hiroshima. Earthy undertones, usually in the background. Rich flavor, quite nose. Representative Sake Brands: Kamoizumi and Fukucho from Hiroshima. Two very different styles, the former being wilder and earthy and the latter being softer and sweeter.

7. Tamazakae Rice

From Tottori and Shiga. Soft and deep, with complex background activity when brewed right. Representative Sake Brands: Kimitsukasa (Tottori ). Hard to find but at Akaoni.

8. Kame no O

From Niigata and Yamagata. Rich and flavorful and a bit drier and more acidic than other rice types, but I have not had enough to intelligently comment. Representative Sake Brands: Although there are several across Niigata and Tohoku, look for Kame no O (Niigata, Kusumi Shuzo).

9. Dewa San San

From Yamagata and Niigata. Complex, not so dry, midly fragrant. Top of PageRepresentative Sake Brands: Fumitoi (Yamagata). Bottles are clearly marked with blue sticker, so easy to find Dewa 33 sake, always from Yamagata.

Rice Milling – Seimaibuai

Premium sake is brewed with special rice in which the starch component (the shinpaku or “white heart”) is concentrated at the center of the grain, with proteins, fats, and amino acids located toward the outside.

Milling

With increased milling, one can remove more of the fats, proteins, and amino acids that lead to unwanted flavors and aromas in the brewing process. Ginjo-shu (premium sake) has at least 40% or more milled away. Daiginjo (super premium sake) has at least 50% or more milled away.

Seimaibuai = Degree rice is milled before brewing

Yamada Nishiki Rice

A top-grade sake rice

Unmilled

45% Milled Away

Seimaibuai = 55%

Ginjo Grade

55% Milled Away

Seimaibuai = 45%

Daiginjo Grade

Rice and Sake Prior to 1945

Rice has always been a staple part of the Japanese diet. Up until roughly 50 years ago, rice was in short supply, with production volumes unable to meet domestic demand. Thus, the rice available for sake brewing was understandably limited, and brewing itself was confined to the winter months, when lower temperatures and cleaner winter air provided the best conditions for brewing and storage (natural refrigeration helped keep sake fresh for consumption months after it was brewed). Such conditions made large-scale brewing unfeasible until recent times, and resulted in regional sake brands that closely matched the local climate, cuisine, and tastes of the local population. These fairly distinct regional styles can still be identified today.One exception, however, is a generic type of sake produced during the Edo period (1600-1868). During this period, the new Warrior Class (samurai) had wrested power from the nobility, and demand for sake increased dramatically amongst these warriors. Sake brewers (most notably in the Nada brewing region between Kobe and Osaka) began to produce sake with a refined flavor that appealed to these upper-class Edo consumers. Although Nada-type sake had no overwhelmingly strong characteristics, there was nothing to dislike about it, and its appeal was therefore widespread . Interestingly enough, its appeal is still strong today.

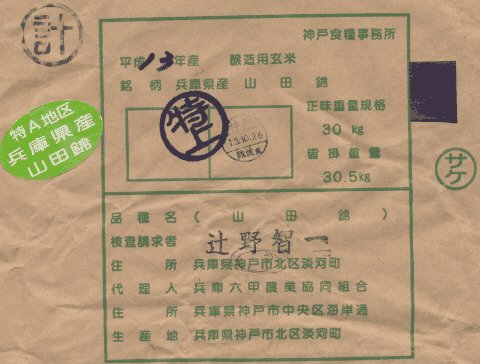

Rice bag

When the sake rice arrives at the sake brewery, it comes as genmai (unmilled, brown rice) in 30 kilogram brown paper bags, with a label on it.

The rice type, Yamada Nishiki, and its prefecture of origin, in this case Hyogo, is printed above the two stamps near the center. Below that, in a big, bold stamp, it says “tokujo,” which indicates it is the highest of the five classes of rice. The smaller stamp is the name of the inspector. The four stamped characters in the lower box are the name of the rice grower, while the green label indicates it is Yamada Nishiki from “Special A designated plots.”