Really?

In last month’s newsletter, we spoke of the middle part of the pressing, and its numerous names. In other words, when the rice solids that remain after fermentation are filtered away, via a press of one sort of another, the terms nakagumi, nakadare and nakadori all mean the same thing, and all refer to the middle part, which is what comes out after the rough first part but before the start of the tired final bits. In other words, the middle part is the best.

In last month’s newsletter, we spoke of the middle part of the pressing, and its numerous names. In other words, when the rice solids that remain after fermentation are filtered away, via a press of one sort of another, the terms nakagumi, nakadare and nakadori all mean the same thing, and all refer to the middle part, which is what comes out after the rough first part but before the start of the tired final bits. In other words, the middle part is the best.

And there is no end to the list of vaguely defined and less than universally applied terminology in the sake world. It keeps things delicately balanced on that fine line of interesting and frustrating.

Another variation of sake worth knowing about is something called jikagumi, which can be loosely but understandably translated as “directly from the press.” As might be clear from that English rendering, jikagumi on a label means that the sake was bottled directly from the pressing apparatus.

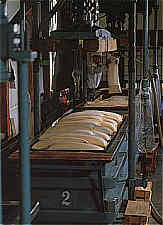

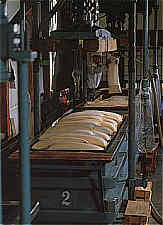

While that pressing apparatus may have been a modern machine (good), a traditional fune box press (better) or just drip-pressed (best), the sake in  that bottle went directly there. This differs from the norm in that most sake is first sent to a big tank where it all sits for a spell. Further sediment will settle, and the sake in that one tank is all thereby guaranteed to be uniform in taste and aroma.

that bottle went directly there. This differs from the norm in that most sake is first sent to a big tank where it all sits for a spell. Further sediment will settle, and the sake in that one tank is all thereby guaranteed to be uniform in taste and aroma.

Furthermore, almost all kura will then blend the tanks of a given product brewed in that year to make sure that each bottle tastes the same. But jikagumi will render each bottle just a little bit different, at least in theory, since (supposedly) it was not blended with any other bottle.

So, not only is jikagumi sake not blended with others, it also should be muroka (unfiltered, or at least, no charcoal or ceramic filtering), genshu (undiluted) and nama (unpasteurized). However, sake can be pasteurized in-bottle as well, so jikagumi can in fact be pasteurized by the time we get it.

Throw all that together and in a sake labelled jikagumi, we can count on having an unfiltered, undiluted sake that has not been blended with any other bottle or batch. This makes it appealing in that each bottle is unique in our time-space continuum, in our universe, and in our reality. Wow.

Throw all that together and in a sake labelled jikagumi, we can count on having an unfiltered, undiluted sake that has not been blended with any other bottle or batch. This makes it appealing in that each bottle is unique in our time-space continuum, in our universe, and in our reality. Wow.

There are just a couple of problems with this: one, they are not allowed to legally do that, and two, practically speaking it is not very realistic.

However, as the term is not legally defined, there is some leeway in the interpretation, and at the end of the day the point is to give us something close to the above. Which is nice.

Legally, when a brewer makes a sake, they press it (filter out the rice solids), and then they must send the sake to one tank, and weigh it. Concurrently they weigh the kasu (lees), or the rice solids remaining from the pressing process. The weight of the sake and the weight of the kasu are recorded – and their sum must equal the weight of the moromi (fermenting mash). Once this has been done and officially recorded, the brewer can bottle the sake, but not before. The point is, of course, to make sure that no sake slips through the tax-cracks.

So from that point of view, jikagumi is not legal. However, thanks to the vagueness of things in Japan, some tax authorities may allow a brewer to bottle it directly, and count the number of bottles multiplied by the volume of each. It should be the same thing, right? Indeed. And surely that is how some places are handling it. Prolly.

Also, practically speaking, it is very labor intensive and a huge hassle to hold one bottle after another under a funnel gathering sake dripping from the  press. We are talking like 2500 bottles for an average sized tank of premium sake, one after another. One. After. Another. Sure, the whole batch need not be done that way, and only a few bottles could be labelled as such. But still: it’s “hassle city.”

press. We are talking like 2500 bottles for an average sized tank of premium sake, one after another. One. After. Another. Sure, the whole batch need not be done that way, and only a few bottles could be labelled as such. But still: it’s “hassle city.”

And in fact, when sake is pressed, it is first allowed to gather in a small holding tank called a kame, and as the kame is filled it is repeatedly pumped to a larger tank. So in truth, something called jikagumi would not even be allowed to gather in the kame. To not do this would call for changes and tweaks that would drastically affect the flow of things.

Yes, it can be done. But it has legal and practical limitations. But yes, it is being done, at least based on the fact that sake labelled jikagumi are out there.

However – and this is important – the term is not legally regulated. So in truth a brewery does not have to it by any set of rules at all. Just because  jikagumi is written on the label does not legally mean that anything had to happen or not happen. Trust that no one is trying to fool us here, but rather that some leeway of execution exists.

jikagumi is written on the label does not legally mean that anything had to happen or not happen. Trust that no one is trying to fool us here, but rather that some leeway of execution exists.

But knowing what jikagumi is (sake bottled directly from the press), and also knowing what it should not be (legally or practically doable), we are left with what the term actually implies.

And that is this: a unique sake to which as little as possible has been done between brewing and bottling. Therein lies its goodness, and its appeal.

In truth, sticking to strict definitions will not serve us here. (They rarely do in the sake world, but I digress.) The spirit of things is what is important.

There was, a few years ago, a spate of jikagumi sake. I recall seeing lots of them during seasonal tastings, usually from smaller brewers with a willingness to experiment and create more appealing sake. But then, I noted that less and less of them were visible.

Upon inquiry, it was as I expected, and as readers might infer from the above. In other words, because the term was not likely to be exactly as it was suggesting, and because there were potential legalities involved, some of the brewers using the term began to steer clear of it, opting for instead other appealing marketing terms. So as quickly as it appeared, it is fading from lexicons a bit. Yes, there are jikagumi sake out there, and yes, they are potentially special and wonderful. But they will not likely constitute a trend with any momentum.

So a sake with jikagumi on the label might not really be so; but it will be as close to that as was legally and practically possible. Enjoy it for what it is.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com.

The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com.

Note that different kura (breweries) have different scales of operation. Some brew lots more than others. Accordingly, when each kura stops and starts for the year varies hugely. The less the brew, the later in the year they begin, and the sooner they finish. Conversely, the larger brewers start earlier and earlier, some approaching late summer as their starting point, and approaching early summer (of the next year) as their wrap-up for the season.

Note that different kura (breweries) have different scales of operation. Some brew lots more than others. Accordingly, when each kura stops and starts for the year varies hugely. The less the brew, the later in the year they begin, and the sooner they finish. Conversely, the larger brewers start earlier and earlier, some approaching late summer as their starting point, and approaching early summer (of the next year) as their wrap-up for the season. The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com. There are but 12 seats remaining open as of today, New (Brewing) Year’s day, 2015!

The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com. There are but 12 seats remaining open as of today, New (Brewing) Year’s day, 2015!