How many producers, how much sake?

As interest in sake grows around the world, naturally enough more and more people express curiosity about the sake industry at its source and origin: Japan.

As interest in sake grows around the world, naturally enough more and more people express curiosity about the sake industry at its source and origin: Japan.

There are many angles from which the industry can be viewed and analyzed. Certainly sales growth and production numbers are one such metric. And as important as they are, those numbers are in constant flux these days. Sales of premium sake grows but overall production still drops as the older generation that was the main market for inexpensive sake gradually passes on. Certainly the growth of premium sake is a more appealing number, and surely it is a better indicator of what to expect in the future.

Another metric, one that is more tied to the traditional infrastructure of sake brewing, is the number of brewers active in the industry. And even these numbers can be confusing and open to interpretation.

For example, one survey on sake exports mentioned that of 1613 companies surveyed, 1526 responded. However, there certainly are not 1613 active sake brewers. It makes more sense when we realize that some companies that just bottle product also need licenses. Furthermore, there are a good-sized handful of kura that are no longer brewing, but refuse to throw in the towel, and so are “taking a break” from sake-producing activities. And, there are some companies – I would estimate ten percent – that have more than one facility, each calling for a separate license. So bundle all those together and perhaps we will get to 1613 or so.

For example, one survey on sake exports mentioned that of 1613 companies surveyed, 1526 responded. However, there certainly are not 1613 active sake brewers. It makes more sense when we realize that some companies that just bottle product also need licenses. Furthermore, there are a good-sized handful of kura that are no longer brewing, but refuse to throw in the towel, and so are “taking a break” from sake-producing activities. And, there are some companies – I would estimate ten percent – that have more than one facility, each calling for a separate license. So bundle all those together and perhaps we will get to 1613 or so.

Another survey by the National Tax Administration determined that during the brewing season that ended in July of 2015, there were 1225 sake-brewing facilities, down 11 from the previous year. However: there are breweries in existence that do not actually brew themselves, for any one of a myriad of reasons. They instead outsource it from factories that are under-capacity, and bottle it and sell it as their own. Some do this with only part of their lineup, others do it for all the sake they sell.

Practices like this are good for small companies with a local market but that might not have the manpower or capital to actually produce it anymore. It can also be helpful to the outsourcing company as well. So while not everyone would enthusiastically support this sector, it fills a need.

When I arrived in Japan in 1988, there were 2055 kura selling sake. Now there are 1225. So we are down 830 sakagura in 28 years.

Based on estimates from traveling the country, working in the industry, and actually counting breweries all around the country (I have a lot of time on my hands…), all observations indicate that there are probably close to 1000 sake companies actually making sake. And that may be a high-end estimate.

So, how many sake breweries are there in Japan? About 1600 with licenses, about 1200 selling product, and about 1000 actually brewing the stuff.

Amongst those thousand, how much sake is being made? About 550 thousand kiloliters a year (of recent). Let that number sink in: over half a million kiloliters. Of that, 13 percent is ginjo (including its four subclasses), and 12 percent is junmai-shu. Interestingly, just a scant 20 years ago, both ginjo and junmai were but four percent of production each.

Amongst those thousand, how much sake is being made? About 550 thousand kiloliters a year (of recent). Let that number sink in: over half a million kiloliters. Of that, 13 percent is ginjo (including its four subclasses), and 12 percent is junmai-shu. Interestingly, just a scant 20 years ago, both ginjo and junmai were but four percent of production each.

How much rice did the industry use last year? About 250 thousand tons of genmai (unmilled rice), or 164 thousand tons of milled rice. Let that number sink in too. The average seimai-buai (milling rate) was 65 percent.

Of the 1225 kura out there, 41 are considered large, i.e. 1300kl or more. All 41 of these companies export sake. Of the small companies, the tiny craft brewers sector, 93 percent export sake. But still, 70 percent of all sake exports come from the big 41 kura. Indeed, the polarization of the sake industry is very interesting.

In spite of all this, only three percent of all sake brewed is exported. Only. Three. Compare that with the  twenty to thirty percent of French and Italian wines that are exported from those respective countires. Or, compare that with scotch whiskey, for which 90 percent of all production is exported. Wow. Either we have a lot of catching up to do (the sake glass is half empty!) or the sake future is so bright, we gotta wear shades when we drink it (the sake glass is half full!).

twenty to thirty percent of French and Italian wines that are exported from those respective countires. Or, compare that with scotch whiskey, for which 90 percent of all production is exported. Wow. Either we have a lot of catching up to do (the sake glass is half empty!) or the sake future is so bright, we gotta wear shades when we drink it (the sake glass is half full!).

Either way you look at it, start by filling the sake glass up back to the brim, and enjoy it. If everyone does that, the sake future is indeed a bright one.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The next Sake Professional Course will be held in Las Vegas Nevada, August 8~10, 2016.

No sake stone remains left unturned! Learn more here . Interested? Please send an email to sakeguy@gol.com today.

Last month in this newsletter we talked about aged sake, and pointed out that, although it is not quite mainstream, matured sake, known as koshu or chouki jukusei-shu, can be extremely interesting. And that is one reason the Nippon Jozo Kyokai, i.e. the Brewing Society of Japan introduced above (BSJ), a while ago began the One-Hundred Year Aged Sake Project.

Last month in this newsletter we talked about aged sake, and pointed out that, although it is not quite mainstream, matured sake, known as koshu or chouki jukusei-shu, can be extremely interesting. And that is one reason the Nippon Jozo Kyokai, i.e. the Brewing Society of Japan introduced above (BSJ), a while ago began the One-Hundred Year Aged Sake Project. there will sit on wooden (hinoki, like cypress) shelves with no metal anywhere near them. The rest, stored at Nodai, will be handled by placing the bottles inside metal tanks. Temperatures will be maintained between 15C and 20C.

there will sit on wooden (hinoki, like cypress) shelves with no metal anywhere near them. The rest, stored at Nodai, will be handled by placing the bottles inside metal tanks. Temperatures will be maintained between 15C and 20C. Along with the one bottle of sake destined to sit a full century, each kura submitted ten smaller bottles (720 ml) to be used at ten along-the-way tastings to be held every ten years. The first of those tastings was held this past November, exactly ten years since it all was laid down. I was fortunate enough to be invited to that tasting, and even if only for the uniqueness of it, the event was fascinating.

Along with the one bottle of sake destined to sit a full century, each kura submitted ten smaller bottles (720 ml) to be used at ten along-the-way tastings to be held every ten years. The first of those tastings was held this past November, exactly ten years since it all was laid down. I was fortunate enough to be invited to that tasting, and even if only for the uniqueness of it, the event was fascinating.

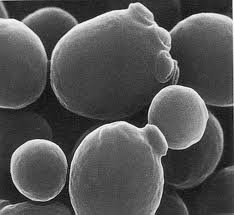

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake. industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter. shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.” Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.

Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.