In all its historical glory…

Each year in May, the most prestigious sake contest in the world is held in

Each year in May, the most prestigious sake contest in the world is held in

Hiroshima. The Zenkoku Shinshu Kampyoukai is a tasting of newly-brewed sake from all over Japan, and is a measure of the technical skill of the brewers in the industry. Its purpose is to encourage the brewing industry to constantly work to push the envelope of brewing expertise.

The name of the event is best translated as the National New Sake Tasting Appraisal, although for some reason the official English name is the Annual Japan Sake Awards.

This year, the 103rd running of the event, I was so privileged as to be the first person outside of the sake industry to participate as a judge in the finals. It was an incredibly amazing thing to do, and I really felt the pressure of the responsibility. And it may have been the coolest thing I have ever had the opportunity of experiencing.

The organization that runs the contest is the National Research Institute of Brewing, which was for most of its 111 year existence a government entity, although that changed a few years back.

Rather than drone on about details, here I want to highlight some of the special characteristics and idiosyncrasies of the contest, and a bit about how the tasting is conducted, all with the goal of promoting more interest in the yearly event.

Rather than drone on about details, here I want to highlight some of the special characteristics and idiosyncrasies of the contest, and a bit about how the tasting is conducted, all with the goal of promoting more interest in the yearly event.

This year, 852 of the 1200-odd sake breweries in Japan submitted a sake to the contest. That number is actually up by seven from last year, even though the number of active breweries declined a bit. This is likely due a changing of the guard in the industry, with younger brewery owners perhaps a bit more enthusiastic than their predecessors.

It is not the be-all end-all of sake contests, nor is it universally loved. A few brewers choose to summarily pass and not even play the game. And most consumers here in Japan are not even aware of it! But still, it is historically, culturally and technically a very interesting event even if it does have a narrow focus.

It works thusly: All the sake is tasted blindly in a preliminary round by a panel of judges over three days. Each judge tastes solo, with no discussion of merits or faults. And the scoring is scathingly simple: the sake is assessed a 1 (the best) to a 5 (the worst). In the preliminary round, comments are also recorded for feedback to the brewers. Those that score well enough advance to the final round. While there is no clear dividing line, it usually ends up being about half of the sake.

It works thusly: All the sake is tasted blindly in a preliminary round by a panel of judges over three days. Each judge tastes solo, with no discussion of merits or faults. And the scoring is scathingly simple: the sake is assessed a 1 (the best) to a 5 (the worst). In the preliminary round, comments are also recorded for feedback to the brewers. Those that score well enough advance to the final round. While there is no clear dividing line, it usually ends up being about half of the sake.

A couple of weeks later, the final round takes place, with a judging by a

panel of 24 judges over two days. This time, it is even more brilliantly (brutally?) simple: each sake is assessed a 1, a 2 or a 3. That’s it. Full stop. No discussion, no comments; do not pass go, do not collect $200.

And after this round, a slightly vague clean break in the scores is again used as the dividing line. Those that do well enough here (again, usually about half of the qualifying sake) are awarded a “Kinsho,” or gold medal. The remaining half of the sake that made it to this round are recognized as well.

The sake are of course tasted blindly. They are not arranged geographically or in any logical order such as that. They are, however, clustered into groups of similar aromatic potency. The thinking is that a very aromatic sake may impair the taster’s ability to be fair to a subsequent sake that is less fruity. So all the submissions have an aromatic component called ethyl caproate measured using a spectrometer before the event, and are presented in groups of their perfumed peers, so to speak.

The sake are of course tasted blindly. They are not arranged geographically or in any logical order such as that. They are, however, clustered into groups of similar aromatic potency. The thinking is that a very aromatic sake may impair the taster’s ability to be fair to a subsequent sake that is less fruity. So all the submissions have an aromatic component called ethyl caproate measured using a spectrometer before the event, and are presented in groups of their perfumed peers, so to speak.

The sake submitted by most of the breweries is a bit intense, kind of like daiginjo on steroids. It is not normal sake available on the market (with some exceptions), but is brewed especially for this contest. While some folks may (and some do) ask “what’s the point?,” keep in mind the purpose here is to assess and promote technical skill. Odd though it may sound, long-session drinkability is not the major consideration.

And as a rational concession to this point, we were instructed that we could lower our score of a sake by one point if we felt that, as good and flaw-free as it might be, it was not something we could chill out with and actually drink. This was, I thought, a very reasonable way to do things.

In terms of actual execution, the 24 of us had 50 minutes to taste 50 sake, which was just about the right amount of time. Then we had a ten minute break, and we went on to the next 50 sake in 50 minutes. We went through five increasingly grueling rounds of this on day one, and three-and-a-half rounds on day two.

I imagine that the preliminary tasting is harder, since by the time we got to them in the finals, the weird stuff had been weeded out. Having said that, I had trouble assessing a score of “3” to many of the sake, since everything there had already cleared the preliminaries!

Almost all of the sake submitted were made using some added alcohol, i.e. are not junmai types. This  makes sense since the added alcohol helps bring out flavor and aroma (the sake are also watered down again, so are not, in the end, fortified). Nevertheless, there were 121 junmai sake in there, up seven from last year.

makes sense since the added alcohol helps bring out flavor and aroma (the sake are also watered down again, so are not, in the end, fortified). Nevertheless, there were 121 junmai sake in there, up seven from last year.

Interestingly, I heard one industry expert vociferously complain about the junmai submissions. He feels that some brewers just unthinkingly threw a junmai type in there, not expecting it to win, but rather to express their commitment to fanatical junmai-ism, so to speak, or rather against the practice of adding alcohol.

“It is distracting to the judges that are trying to concentrate, and such sake is irrelevant to the contest. It is as if they are sabotaging the dignity of the event,” he explained. Certainly this is only one opinion, but I can very clearly see its merits, and his point as well.

In the end, 415 received an award this year, of which 222 were gold medals.

As has been the case for the past several years, the Tohoku region (the six prefectures on the northern extreme of Japan’s main island, Honshu) kicked butt again. In particular, Fukushima Prefecture won 24 gold medals, far away from the next-most of 15 won by Yamagata (also in Tohoku) and Niigata. The dominance of the region continues.

One interesting idiosyncrasy of the event, evident in the photos here, is that the sake is all tasted from simple amber-colored tumblers. Why amber? Because that hides any color in the sake, which is done, it is said, to prevent tasters from imposing a prejudice on sake based on any semblance of amber color which might skew their opinion. Are such glasses, with their simple shape, the best for sake like this? Not likely, in the opinion of many. But at least all the sake are tasted under the same conditions. I am also not sure that the colored glass solution is the most appropriate solution to misplaced perceptions. But this is the way it has long been done.

One interesting idiosyncrasy of the event, evident in the photos here, is that the sake is all tasted from simple amber-colored tumblers. Why amber? Because that hides any color in the sake, which is done, it is said, to prevent tasters from imposing a prejudice on sake based on any semblance of amber color which might skew their opinion. Are such glasses, with their simple shape, the best for sake like this? Not likely, in the opinion of many. But at least all the sake are tasted under the same conditions. I am also not sure that the colored glass solution is the most appropriate solution to misplaced perceptions. But this is the way it has long been done.

In the end, the Zenkoku Shinshu Kampyoukai has a long and storied history, complete with false starts and offshoots. And it is a brilliant yearly event that has maintained its significance in the sake industry. Furthermore, the NRIB is reaching out to the world with the event, and it is important to the sake industry to support that.

As evidence of that reaching out, you can learn more about the NRIB in English here. Also, you can learn more about the particulars of the contest here. And finally, you can see the results in English here.

Should the contest and the NRIB interest you, by all means, please check out all three.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sake Professional Course in Florida, August 17-19

Thanks to everyone’s support and the current popularity of sake, the Sake Professional Course in Las Vegas, June 1-3, is full. The next Sake Professional Course is scheduled for Miami Beach Florida, August 17-19, at the Shelborne Wyndham Grand Hotel, within which sits the South Beach Morimoto Restaurant. This is the first Sake Professional Course to be held in this part of the country and promises to be a particularly enjoyable running of the course.

Thanks to everyone’s support and the current popularity of sake, the Sake Professional Course in Las Vegas, June 1-3, is full. The next Sake Professional Course is scheduled for Miami Beach Florida, August 17-19, at the Shelborne Wyndham Grand Hotel, within which sits the South Beach Morimoto Restaurant. This is the first Sake Professional Course to be held in this part of the country and promises to be a particularly enjoyable running of the course.

More information is available here, and testimonials from graduates can be perused here as well. The three-day course wraps  up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

Following that, the next one is tentatively scheduled for the fall in the northeast part of the US. If you are interested, feel free to send me an email to that purport now; I will keep track of your interest!

At what temperature should you enjoy sake?

At what temperature should you enjoy sake?

Note the white opaque starch packet in the center of many of the grains.

Note the white opaque starch packet in the center of many of the grains. Next, the white powder (called nuka) left on the rice after polishing is washed away, as this makes a significant difference in the final quality of the steamed rice. (It also affects the flavor of table rice; try washing your rice very thoroughly and notice the difference in consistency and flavor.) Following that, it is soaked to attain a certain water content deemed optimum for steaming that particular rice. The degree to which the rice has been milled in the previous step determines what its pre-steaming water content should be. The more a rice has been polished, the faster it absorbs water and the shorter the soaking time. Often it is done for as little as a stopwatch-measured minute, sometimes it is done overnight.

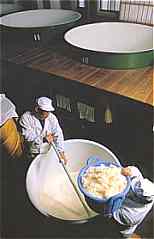

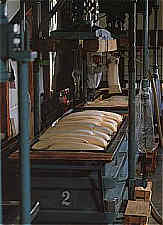

Next, the white powder (called nuka) left on the rice after polishing is washed away, as this makes a significant difference in the final quality of the steamed rice. (It also affects the flavor of table rice; try washing your rice very thoroughly and notice the difference in consistency and flavor.) Following that, it is soaked to attain a certain water content deemed optimum for steaming that particular rice. The degree to which the rice has been milled in the previous step determines what its pre-steaming water content should be. The more a rice has been polished, the faster it absorbs water and the shorter the soaking time. Often it is done for as little as a stopwatch-measured minute, sometimes it is done overnight. and brought to a boil; rather, steam is brought up through the bottom of the steaming vat (traditionally called a koshiki) to work its way through the rice. This gives a firmer consistency and slightly harder outside surface and softer center. Generally, a batch of steamed rice is divided up, with some going to have koji mold sprinkled over it, and some going directly to the fermentation vat. (Photo at left: rice steaming in koshiki, or vat).

and brought to a boil; rather, steam is brought up through the bottom of the steaming vat (traditionally called a koshiki) to work its way through the rice. This gives a firmer consistency and slightly harder outside surface and softer center. Generally, a batch of steamed rice is divided up, with some going to have koji mold sprinkled over it, and some going directly to the fermentation vat. (Photo at left: rice steaming in koshiki, or vat). This is the heart of the entire brewing process, really, and could have several chapters, if not books, written about it. Summarizing, k(LEFT) Koji being cultivated in small trays (Right) A grain of rice cultavated with koji mold (photos by Kenji Nachi)oji mold in the form of a dark, fine powder is sprinkled on steamed rice that has been cooled. It is then taken to a special room within which a higher than average humidity and temperature are maintained. Over the next 36 to 45 hours, the developing koji is checked, mixed and re-arranged constantly. The final product looks like rice grains with a slight frosting on them, and smells faintly of sweet chestnuts. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, and is always made fresh and used immediately. Therefore, any one batch goes through the “heart of the process” at least four times. (Photo: Koji being cultivated in small trays, and a grain of rice cultavated with koji mold).

This is the heart of the entire brewing process, really, and could have several chapters, if not books, written about it. Summarizing, k(LEFT) Koji being cultivated in small trays (Right) A grain of rice cultavated with koji mold (photos by Kenji Nachi)oji mold in the form of a dark, fine powder is sprinkled on steamed rice that has been cooled. It is then taken to a special room within which a higher than average humidity and temperature are maintained. Over the next 36 to 45 hours, the developing koji is checked, mixed and re-arranged constantly. The final product looks like rice grains with a slight frosting on them, and smells faintly of sweet chestnuts. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, and is always made fresh and used immediately. Therefore, any one batch goes through the “heart of the process” at least four times. (Photo: Koji being cultivated in small trays, and a grain of rice cultavated with koji mold). Photo at right: the moto, or shubo yeast starter, foaming away.

Photo at right: the moto, or shubo yeast starter, foaming away. When everything is just right (no easy decision!), the sake is pressed. Through one of several methods, the white lees (called kasu) and unfermented solids are pressed away, and the clear sake runs off. This is most often done by machine, although the older methods involving putting the moromi in canvas bags and squeezing the fresh sake out, or letting the sake drip out of the bags, are still used. (Photo at right: bags of moromi from which sake is being drip-pressed. Below Photo: a fune, used for pressing sake out of bags of moromi).

When everything is just right (no easy decision!), the sake is pressed. Through one of several methods, the white lees (called kasu) and unfermented solids are pressed away, and the clear sake runs off. This is most often done by machine, although the older methods involving putting the moromi in canvas bags and squeezing the fresh sake out, or letting the sake drip out of the bags, are still used. (Photo at right: bags of moromi from which sake is being drip-pressed. Below Photo: a fune, used for pressing sake out of bags of moromi). Most sake is then pasteurized once. This is done by heating it quickly by passing it through a pipe immersed in hot water. This process kills off bacteria and deactivates enzymes that would likely adverse flavor and color later on. Sake that is not pasteurized is called namazake, and maintains a certain freshness of flavor, although it must be kept refrigerated to protect it.

Most sake is then pasteurized once. This is done by heating it quickly by passing it through a pipe immersed in hot water. This process kills off bacteria and deactivates enzymes that would likely adverse flavor and color later on. Sake that is not pasteurized is called namazake, and maintains a certain freshness of flavor, although it must be kept refrigerated to protect it.