|

The People The People

Kuramoto, Toji and Kurabito

Sake is produced by the kuramoto (brewery owner), the toji (head sake brewer), and the

kurabito (brewery workers). In economic terms, creating the product calls for land, finances and raw materials. The kuramoto is responsible for

procuring these, while the toji is responsible for the actual brewing and the hiring and management of the kurabito. Moreover, since sake is brewed only in the winter, the toji and

kurabito are essentially "contract" workers.

The Toji System The Toji System

The toji, or head brewer, is generally associated with one ryuha, or "school" of brewing. These toji ryuha are tied closely to various regions

throughout Japan, and there are perhaps 25 schools of toji in existence now. Each school has its own style, to be sure, and that style is

evident in the sake they brew, but the differences between various schools of toji is not what it was long ago. Long ago, it was all quite secretive, and the methods employed and refined

by one group were never disclosed to other groups. But, over the past several decades, toji and brewers from all over the country readily share information in their shared desire

to make better sake.

In part, the toji system came about with a little help from the government. In 1798 the Shogunate formalized an economic system based on rice. In

order to establish tight control, the government decreed that no sake brewing was permitted before the Autumn Equinox. Although not much could be done

in the warmer seasons anyway, sake brewers now had to go into the boonies to get the farmers who found themselves with too much free time in the winter. In part, the toji system came about with a little help from the government. In 1798 the Shogunate formalized an economic system based on rice. In

order to establish tight control, the government decreed that no sake brewing was permitted before the Autumn Equinox. Although not much could be done

in the warmer seasons anyway, sake brewers now had to go into the boonies to get the farmers who found themselves with too much free time in the winter.

Toji for the most part are, in the off-season, farmers

and fishermen. During the spring, summer and fall, they grow rice or work on fishing boats in their home regions. When the fall harvest is over, or the fishing

season ends, there is no longer any work in their villages. This is the season when they head off to sake breweries to work. In Japanese, this traveling for

seasonal employment is called "dekasegi." Toji for the most part are, in the off-season, farmers

and fishermen. During the spring, summer and fall, they grow rice or work on fishing boats in their home regions. When the fall harvest is over, or the fishing

season ends, there is no longer any work in their villages. This is the season when they head off to sake breweries to work. In Japanese, this traveling for

seasonal employment is called "dekasegi."

The various toji schools are usually centered in the snowy regions of Japan, like

the northern Tohoku region and Hokuriku region. Although the dekasegi system of travelling far from home for seasonal work was never limited to the sake brewing

industry, the pay and status of sake laborers was always relatively higher than other seasonal labor jobs. In general, the competition for jobs in the sake industry has thus

been more intense than in other industries employing dekasegi laborers. For more on toji schools, click here. The various toji schools are usually centered in the snowy regions of Japan, like

the northern Tohoku region and Hokuriku region. Although the dekasegi system of travelling far from home for seasonal work was never limited to the sake brewing

industry, the pay and status of sake laborers was always relatively higher than other seasonal labor jobs. In general, the competition for jobs in the sake industry has thus

been more intense than in other industries employing dekasegi laborers. For more on toji schools, click here.

Learning the Trade Learning the Trade

A toji basically learns his skill through on-the-job training. There are no texts, and the only way to learn is by watching. In the old days, no one taught anyone

else by direct instruction; one was expected to watch and learn. This allowed one to develop a very deeply embedded and strong sense about what to do in each

situation. As a result, if you gathered together 100 toji, you would likely find 100 different brewing styles. Indeed, the Japanese saying Sakaya Banryu was

coined to express this wide divergence in toji styles.

In modern times, however, this system of learning only by watching has changed somewhat. Today, the

government and toji unions encourage those wanting to become toji to formally study fermentation and chemistry.

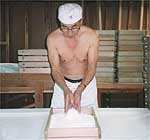

A Typical Toji Work Day

What precisely does a toji do? Let's look at a typical day during the high season of sake brewing. The toji,

along with the other brewing craftsmen (kurabito), gets up about five in the morning. The first thing to do is to check on the state of the koji. Koji development is an extremely

important step in the brewing process, in which the starch in the rice is converted into sugars. Koji is created by propagating koji mold spores (called aspergillus oryzae in

English) onto rice. To do this properly, the koji must be mixed regularly and have its temperature checked constantly. This is the first order of business in the early morning.

Next, toji check the status of the various tanks of fermenting sake mash. This mash, called moromi in Japanese, is a mixture of koji, rice, water, and yeast. The mash must

undergo fermentation to yield alcohol, and the typical fermentation period lasts two to three weeks. However, premium ginjo-shu sake takes longer (usually one month) to ferment.

During the fermentation period, the toji will check daily the status of each moromi tank.

This often means making a chemical analysis of the moromi to determine if various compounds are sufficiently present. But the toji does not rely purely on chemical

analysis. He relies on his experience and eyes to judge the condition of the mash. He looks at the foam on the surface of the moromi, how much carbon dioxide is emanating

from it, the amount and appearance of the foam, and even the sound of the foam as it

churns and bubbles pop. The toji call this "talking to the moromi." It 's like judging a

baby's health by listening to the baby's crying. Then, based on this information, adjustments are made.

For example, if the yeast is particularly active and the fermentation is proceeding too quickly, he may cool the tank down a bit to slow the progress of the fermenting moromi.

Just how many degrees it needs to be chilled would be a decision based on the toji's experience. Before there were any major technological developments, sake was

brewed exclusively by these kinds of methods, but even today in the age of chemical analysis and modern technology, these skills are just as important as the analysis and

modern equipment.

After checking on the moromi and koji, the toji eat breakfast. Following that,

preparations are made for the sake that will be brewed that day. This includes washing rice, steaming large amounts of rice, cooling the rice after steaming, adding it

to the correct fermenting tanks, and making koji.

There are usually several types of sake being brewed at any one time, each calling for

different types of sake rice. Toji must be very careful to keep their rices separate. Also, sake that has completed its fermentation period and is ready will be pressed to

separate the clear sake from the remaining rice solids to give what is called genshu, or pure undiluted sake. This process can take all day and last into the evening.

After dinner, they take a break prior to the late-evening check and mixing of the koji. They go to sleep about ten o'clock, with the same work awaiting them the next morning.

Today, scientific theories and systematic testing provide viable explanations for the fermentation process, and the toji craft has lost some of its "magic and mystery." Yet, we

must still admire the toji, for they are dealing daily with a fermentation process that involves microorganisms too small to be seen by the naked eye. Some of these

microscopic organisms are floating around in the air, and although some are beneficial to sake production, others are detrimental. Just how to balance the effects of these

organisms is something the toji does not with his eyes, but based on his experience, his sense, and his intuition. And in the end a great toji creates a great work of art that

science alone could never achieve through automation. Making sake is indeed deep and complicated work. It may seem that a toji's work is one of simple repetition, but

each day he works with nature, not against it, to seemingly control organisms he cannot see, based on what could be called "the eyes of his heart."

Decline in Number of Toji

Along with a general decline in the number of sake breweries in Japan, the number of

toji as well is declining owing to advanced age, the lack of successors, and the utilization of mass-production techniques. The average toji age is 65. Successors are

hard to find, as more and more Japanese youth prefer the excitement and opportunites of the big cities to life in small farming and fishing villages. The toji take pride in their

work, but they also know it is hard work on a seasonal basis and thus in general they refrain from forcing their children to follow in their footsteps.

The number of toji is expected to decline rapidly in the years ahead, but some kuramoto are working to remedy this situation. Some are moving away from "contracted" seasonal

labor and offering more permanent employment opportunities. Others are attempting to automate certain operations, like bottle transport, which do not require a "handmade"

touch. Some are introducing computers and new technologies to "simulate" -- via fuzzy logic -- the experience and intuition of the toji. Although many smaller brewers are

experimenting with ways to combine automation technologies with centuries-old hand-made brewing techniques, their objectives remain quite different from the large-scale

mass producers of sake. The objective of the small brewer is not to produce greater volume, but rather to continue producing unique "hand-made" sake with technologies

and employment practices  that ensure its future survival. that ensure its future survival.

Famous Toji Schools

There are about 25 toji ryuha throughout Japan. The largest three are by far Nanbu toji from Iwate, Echigo toji from Niigata, and Tajima toji from Hyogo. Their names come

from the old geographical names for their respective regions. As might be expected, Nanbu toji were centered around Tohoku, Echigo toji near Niigata and Kanto, and

Tajima toji in Nada and Fushimi. Other examples include Akitsu toji from Hiroshima, Yamanouchi toji from Akita, and Tanba toji, also from Hyogo.

Although consumer demand has often come to dictate style more than in the past, some semblance of regional distinction remains. Sake made by Echigo toji is quite

often "tanrei karakuchi," or dry and clean. The soft and mellow sake of Nada and Kyoto is indicative of that made by Tajima toji, and Nanbu toji sake is generally simple,

straightforward, but well pronounced; a personal favorite as far as styles go. Others recommendable for their distinction and memorability include the sake of Hiroshima's

Akitsu toji, and that of the Izumo toji of Shimane, albeit a bit harder to find.

As the number of kura (sake breweries) has drastically declined, naturally so has the

number of toji in most ryuha. The number of Echigo toji has dropped to one-third what it was at the beginning of the Showa era, and the number of Tajima toji, the largest at the

beginning of the Showa era, has dropped to one-tenth the number of members. Only the Nanbu toji have retained strength in the ranks, having maintained the same number

of members for the past 40 years or so. This may be due to the training and strict qualifications testing provided. Amongst prize-winning sake, the Nanbu toji names are

appearing with increasing frequency.

With the convenience of modern transportation systems, the toji are venturing farther and

farther from home. They very often travel together with the same crew of kurabito (workers). For example, Nanbu toji and their merry bands can be found as far south as

Kansai. They have come to naturally fill the voids left by the decreasing number of Echigo toji.

As interest increases in the factors that go into brewing good sake, the name of the toji, and where he or she is from, is often listed on the label. Paying attention to toji

helps develop a sense for the particular styles and distinctions of the various regions.

|