The epitome of it all expressed at Kikuyoi

The epitome of it all expressed at Kikuyoi

As the climax of the Sake Professional Course Level II course, we visit a couple of breweries. This year, as is the case most years, we head down to Shizuoka Prefecture a couple hours south, wherein sits majestic Mt. Fuji and about 30 great sake breweries. One of them makes a sake called Kikuyoi.

The toji is also the owner-inherit, Densaburo Aoshima, and their sake is quite popular. It sells out yearly, and they cannot make any more for a number of reasons. They are simply maxed out in terms of capacity, both infrastructurally and in human resources.

Much could be written about Aoshima-san, and in fact I have written about him in my ebook Sake’s Hidden Stories, which you can buy here. One of the most amazing things about him is how he is so into the concept of brewing sake by keiken to kan, or “experience and intuition.” He lives it, and breathes it. He oozes it. He walks it and he talks it. He brews his sake based on his five senses and what they tell him. He does not use email or a cell phone so as not to dullen those five senses. Yet in spite of that borderline fanaticism, he is warm, light-hearted and friendly.

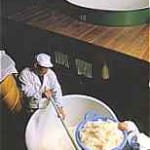

We time our arrival every year so as to see the hugely important step of washing and soaking the rice. As simple as it sounds, the more thoroughly the rice is washed to remove the powder that clings to it from milling, the better the sake can be brewed. And the moisture content after washing and the subsequent soaking determine so much, including how the koji mold will grow, and how fast or slowly the rice will dissolve in the fermenting mash. And not only is precision of moisture content important, so is uniformity: ideally every single grain of the countless number going into a batch should have the same moisture content. Achieving that is easier said than done!

The way this uniformity is usually achieved is to split all the rice to be steamed into (most commonly) 10 kilogram baskets or bags. So if they are steaming 300 kilos, that would be 30 bags or baskets. It could run anywhere from five to fifty, for a reasonably sized batch of hand-crafted sake.

Typically, after soaking they will want the rice to have absorbed 28 to 33 percent more water. So if we use 32 percent for this discussion,  a basket weighing 10 kilos will weigh 13.2 kilos after washing and soaking, and absorbing exactly 32 percent, or another 3.2 kilos of water, in the process. But the rate of absorption is affected by many things: the milling rate, the variety of rice, the year’s harvest, and the weather – just for starters. So, not surprisingly, the speed at which it absorbs water will be different every time. What’s a brewer to do!?

a basket weighing 10 kilos will weigh 13.2 kilos after washing and soaking, and absorbing exactly 32 percent, or another 3.2 kilos of water, in the process. But the rate of absorption is affected by many things: the milling rate, the variety of rice, the year’s harvest, and the weather – just for starters. So, not surprisingly, the speed at which it absorbs water will be different every time. What’s a brewer to do!?

What they do is to test a few baskets. Based on experience and intuition, they soak the first basket for an amount of time they think is right, then weigh it. If it is too heavy, i.e. if too much water was absorbed, they back the time off a bit. If it was too light, i.e. if too little water was absorbed, they let it soak a bit longer. They do this for three or four baskets and then determine the time for that day, and that set of baskets of that rice. Then they soak the remaining baskets for that period of time.

By doing it this way, they can achieve a very uniform moisture content down to about one half of one percent. Read that again and let it sink in again. One half of one percent accuracy, uniformly across hundreds of kilos of rice.

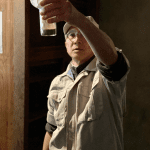

But Aoshima-san is different. He don’t need no stinkin’ clocks or stopwatches; he has his keiken to kan, his experience and his intuition. So what he does is to squat next to the wide but shallow tub in which the very thoroughly washed rice has just been placed, and take a handful of grains into the palm of his hand, keeping hand and rice grains submerged in that cold-ass water. And he watches ‘em. And watches ‘em. And he assesses how much water has been absorbed by seeing how the color around the outside of the grains changes. (Photos of Aoshima-san courtesy of Laura Kading.)

But Aoshima-san is different. He don’t need no stinkin’ clocks or stopwatches; he has his keiken to kan, his experience and his intuition. So what he does is to squat next to the wide but shallow tub in which the very thoroughly washed rice has just been placed, and take a handful of grains into the palm of his hand, keeping hand and rice grains submerged in that cold-ass water. And he watches ‘em. And watches ‘em. And he assesses how much water has been absorbed by seeing how the color around the outside of the grains changes. (Photos of Aoshima-san courtesy of Laura Kading.)

Of course, as he does that, someone else measures the time. And when he says, “Now!” they stop the timer. And he does in fact listen to the numerical results, and adjust the time up or down to increase or decrease water absorption. But he assesses it using his five senses, his experience, and his intuition.

The 20 of us gathered around the washing and soaking setup in a cramped outdoor courtyard behind their brewery, trying to find the balance between being close enough to see but not so close as to be in the way. As he scooped the first few grains from the first basket up into his hands, he still had the leeway to talk to us. He explained the color change, the speed of absorption and what affected that and when, and his objective for that day.

“I’m looking for 32 percent, exactly. It’s rice for koji, so I take it just a bit higher. And it’s Yamada Nishiki at 60 percent, so it absorbs fast, but not nearly as fast as if it were milled to 50% or more,” he explained.

“Today, taking all factors into consideration, I expect it will take nine minutes, plus or minus fifteen to thirty seconds, to achieve that 32 percent,” he summed up.

He continued on about how the rice was cracked this year, and that more cracks appear as you soak it. The problem is, he lamented, that  the cracked rice absorbs water faster than uncracked rice. So having cracked rice in the lot means that it is much harder to obtain uniformity of moisture, since some grains will absorb more water due to their cracks then their uncracked counterparts. And that means that the mold will not grow the same way on all rice, and that different grains will dissolve at different rates. That in turn makes everything less predictable.

the cracked rice absorbs water faster than uncracked rice. So having cracked rice in the lot means that it is much harder to obtain uniformity of moisture, since some grains will absorb more water due to their cracks then their uncracked counterparts. And that means that the mold will not grow the same way on all rice, and that different grains will dissolve at different rates. That in turn makes everything less predictable.

He further explained that while 10 kilogram baskets or bags are the norm, that isn’t precise enough for Mr. Maniacal; as such, he does everything in five kilogram baskets to add even more precision – and hassle of course – to his attention to detail.

As time wore on, he became silent, focusing on the changing surface color of the rice sequestered in his palm. Then he snapped back from his focused reverie, and calmly said, “now!” The timekeeper shouted out, “nine minutes exactly.”

Next, he pulled the basket out, let the excess water drip off a few minutes, and someone hauled it off and weighed it. And the call came from the guy standing in front of the scale: “Thirty two!”

Aoshima-san looked back over his shoulder at me, smiling – yea, verily smirking – with confidence and satisfaction. “Dja hear that? Thirty two exactly. Nailed it!,” he exclaimed. “ Keiken to kan!” Experience and intuition.

Next, to be doubly certain, he soaked the next basked fifteen seconds longer; it ended up at 33 percent. To wrap it up, he soaked the third basket fifteen seconds shorter; not surprisingly it ended up at 31 percent. He then instructed the other workers to soak the remaining few dozen baskets for nine minutes, exactly, and stepped aside to lead us on a tour of the rest of the kura.

Next, to be doubly certain, he soaked the next basked fifteen seconds longer; it ended up at 33 percent. To wrap it up, he soaked the third basket fifteen seconds shorter; not surprisingly it ended up at 31 percent. He then instructed the other workers to soak the remaining few dozen baskets for nine minutes, exactly, and stepped aside to lead us on a tour of the rest of the kura.

In truth, Aoshima-san is just one of many brewers that takes attention to detail as far as he can, and other brewers might express that in other ways that are just as amazing. This uncompromising attitude and practice is endemic to the sake world.

Later, as we ran through a tasting of his sake, he went back to the discussion that started as he palmed the rice in the tub of cold water in the outdoor winter weather. “Actually, it is not that difficult. But you have to do it every single day; that is the only way to get the experience, and the intuition that follows. You gotta live it, that’s all.”

Yeah; that’s all.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances. the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role?

the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role? And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone.

And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone. company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy.

company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy. While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

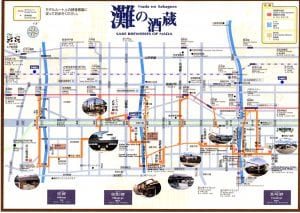

While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.” The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider.

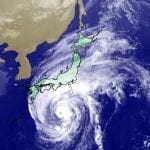

The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider. But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries.

But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries. Surely modern technology in all areas helps this. For example, weather radar lenabled everyone to see the massive typhoon Hagibis that engulfed Japan in early October. This allowed the farmers growing Yamada Nishiki to quickly harvest the rice – albeit a bit earlier than they would normally have done it. An early harvest is much better than a ruined one. More significantly, though, climate change affects things in ways beyond higher temperatures.

Surely modern technology in all areas helps this. For example, weather radar lenabled everyone to see the massive typhoon Hagibis that engulfed Japan in early October. This allowed the farmers growing Yamada Nishiki to quickly harvest the rice – albeit a bit earlier than they would normally have done it. An early harvest is much better than a ruined one. More significantly, though, climate change affects things in ways beyond higher temperatures. Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended.

Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended. Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product.

Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product. When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed.

When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed. characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods.

characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods. And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice.

And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice. temperatures, to get precisely the profile they are looking for. Temperature affects the speed of changes during maturation, as does the choice of aging vessel (bottles or tanks). This allows brewers to tweak their flavor profiles, and maintain consistency throughout the year. But everyone does it a bit differently, and it makes the term aki-agari a tad less universally applicable.

temperatures, to get precisely the profile they are looking for. Temperature affects the speed of changes during maturation, as does the choice of aging vessel (bottles or tanks). This allows brewers to tweak their flavor profiles, and maintain consistency throughout the year. But everyone does it a bit differently, and it makes the term aki-agari a tad less universally applicable. And to make things interesting, some brewers consider hiya-oroshi as just one kind of aki-agari. In truth, that is actually valid thanks to the vagueness of the definition of aki-agari, even if it is a tad confusing. So have fun with that.

And to make things interesting, some brewers consider hiya-oroshi as just one kind of aki-agari. In truth, that is actually valid thanks to the vagueness of the definition of aki-agari, even if it is a tad confusing. So have fun with that. Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity.

Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity. harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.”

harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.” Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle.

Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle. political eras. For example, the Edo era ran from 1604 to 1868, and was named after the capital city, Edo, which later was renamed Tokyo. This span of 264 years was one of relative stability as it was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, a long string of shogun that basically handed power down from father to son.

political eras. For example, the Edo era ran from 1604 to 1868, and was named after the capital city, Edo, which later was renamed Tokyo. This span of 264 years was one of relative stability as it was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, a long string of shogun that basically handed power down from father to son.

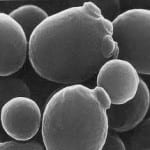

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake.

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake. One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.)

One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.) That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.

That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.