This article originally appeared in the April 15 issue of Sake Industry News.

Amongst the many steps of the sake brewing process, some are more glamorous than others, and that therefore garner more attention. “Koji-making” and “yeast starter” sound so much more romantic than “milling the rice.” As such it becomes easy to dismissively abridge the more mundane-sounding processes, and even more so when modern machines do a much better job than hassle-laden traditional hand-crafted methods.

Amongst the many steps of the sake brewing process, some are more glamorous than others, and that therefore garner more attention. “Koji-making” and “yeast starter” sound so much more romantic than “milling the rice.” As such it becomes easy to dismissively abridge the more mundane-sounding processes, and even more so when modern machines do a much better job than hassle-laden traditional hand-crafted methods.

And rice milling is the epitome of this. We usually say, “first, they mill the rice…” and move on to the more glamorous steps. But that belies how incredibly important milling is. One could say it is the most important step, since if the rice is not milled well – if there are lots of cracked or broken grains as one example – then the rest of the processes will not proceed well and the resulting sake will suffer.

Why, again, do they mill the rice? The objective is to remove fat and protein from the outside of the rice grains while leaving the starch in the middle intact, and doing this in such a way that the rice grains do not crack or break. Protein and fat can give character to sake, but they are usually viewed as the cause of rougher flavors. And avoiding cracking and breaking while milling is important so as to let the microorganisms used in the process to do what they need to do effectively and predictably.

From eons ago, rice in Japan has been milled a bit before being consumed. But really, only the outer eight to ten percent is milled away; that is enough to significantly improve the way it tastes. Long ago rice was milled using using grinding stones, often driven by water wheels when available. But this was rough, and only the very outer portion (that eight to ten percent) could be milled away.

In 1896, the company Satake, located in Hiroshima, developed automatic milling machines that made all that much easier. And that  company grew into the largest rice milling machine company in the world, which they remain today. In the 1930s, Satake went on to develop special milling machines to mill rice especially for sake brewing. These employed harder milling stones that were much larger, and through these developments brewers were able to mill the rice much farther then ever before. This technology led to higher and higher milling rates, and eventually, the advent of ginjo-shu.

company grew into the largest rice milling machine company in the world, which they remain today. In the 1930s, Satake went on to develop special milling machines to mill rice especially for sake brewing. These employed harder milling stones that were much larger, and through these developments brewers were able to mill the rice much farther then ever before. This technology led to higher and higher milling rates, and eventually, the advent of ginjo-shu.

So for a long while, it was all about Satake. But note, the company’s bread and butter (or rice and pickles, as it were) was machines for table rice, a market they dominate today as well. But there are other milling machine producers, and many have come and gone. Today, the other main company that makes rice milling machines is Shin-Nakano. Both are great companies, and both continue to make their presence felt.

Shin-Nakano, while a much smaller producer of milling machines, is part of larger holding company that owns other sake industry businesses, including a couple of sake breweries as well. And they have maintained plenty of relevance by focusing on craft breweries, and offering plenty of added value, in the form of research with backed by proper scientific methods that has from time to time gone against what has been common sense in the industry. For this and other reasons, many sake brewers stick with Shin-Nakano machines, and they are quite visible in the sake world.

But beyond the machines themselves and their producers, there are developments that start out as ideas in the minds of brewers and such, and eventually work their way into the technology. One of those is what is called Henpei Seimai, or flat milling.

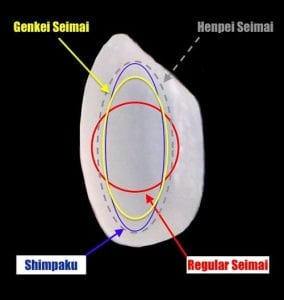

In order to grasp Henpei Seimai, remember that rice grains are not round, but are oblong, kind of like a rugby ball, and the starch center known as a shinpaku within is also basically of that shape. And like many of us human beings, there is much more meat around the midsection than at the top or bottom. This “meat” in sake rice is fat and protein. But when milling machines mill, they take the rugby-ball-shape and make it round by milling evenly everywhere around the grain. This means that, when milling is done, there is more fat and protein around the sides of the shinpaku then at the ends.

In order to grasp Henpei Seimai, remember that rice grains are not round, but are oblong, kind of like a rugby ball, and the starch center known as a shinpaku within is also basically of that shape. And like many of us human beings, there is much more meat around the midsection than at the top or bottom. This “meat” in sake rice is fat and protein. But when milling machines mill, they take the rugby-ball-shape and make it round by milling evenly everywhere around the grain. This means that, when milling is done, there is more fat and protein around the sides of the shinpaku then at the ends.

If they could somehow maintain the oblong shape and mill more around the midsection then at the top or bottom, a higher ratio of fat and protein could be removed. This idea was proposed about thirty years ago by Mr. Tomio Saito, a former Chief Official Appraiser at the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau.

And it worked! The concept was embraced by Daischichi brewery in Fukushima, and others followed soon after that, and Henpei Seimai was born. (Actually, Daishichi takes it a bit further and calls it Cho-henpei Seimai, or “Super Flat Milling.” You can learn more about that here.)

Henpei Seimai does not call for special milling machines. It just calls for modifying and jury-rigging older machines, a lot of skill and a  ton of patience on the part of the miller. But basically things are tweaked so that the rice grains fall in fewer numbers against the milling stone, and maintain a vertical orientation as they do. This means that more gets nicked off the sides each time than the top or bottom, and the henpei seimai goal is achieved. So anyone with the requisite skill and experience can do it, it just takes longer, and uses more energy as well.

ton of patience on the part of the miller. But basically things are tweaked so that the rice grains fall in fewer numbers against the milling stone, and maintain a vertical orientation as they do. This means that more gets nicked off the sides each time than the top or bottom, and the henpei seimai goal is achieved. So anyone with the requisite skill and experience can do it, it just takes longer, and uses more energy as well.

This is obviously appealing to most brewers: remove a higher percentage of fat and protein with less milling. But since it is a hassle, most brewers do not do it. Yet, amongst those that do, Shin Nakano seems to be the machine of choice, (although that is based on observation and word on the street rather than hard statistics).

However: Satake came back into the mix by recently developing a new milling machine that can do Henpei Seimai, but without all the little adjustments that are normally called for. No mess, no stress. Just select “henpei” and it works. It does it faster as well, and uses less energy in doing so.

But they also took it a step further: Satake developed a slightly different milling outcome that they call Genkei Seimai. Genkei means “original shape,” and as can be surmised from the name, it purports to mill the rice in such a way that it ends up closer to the original shape than normal round milling or Henpei Seimai. The result is that there is more fat around the middle than Henpei, but less than regular milling. However, there is less cracking and breaking since the original natural shape remains more integrated.

They have, in fact, just introduced this machine and this way of milling, so there are not enough results in the field to develop an opinion. That will come, and we will look at some preliminary mumblings in a moment. But to me, the most significant thing about all this is that the mighty Satake is actively getting involved in the sake rice milling game again. That bodes quite well for the sake world.

Back to the differences between the milling methods, please refer to the drawing. Regular milling takes a rugby ball and mills it into the shape of a baseball, Henpei Seimai mills more from the fat-laden sides than the ends, and Genkei Seimai is less flat, and mills somewhere in the middle, with the objective being maintaining the original dimensions, so to speak, of the rice grain.

Back to the differences between the milling methods, please refer to the drawing. Regular milling takes a rugby ball and mills it into the shape of a baseball, Henpei Seimai mills more from the fat-laden sides than the ends, and Genkei Seimai is less flat, and mills somewhere in the middle, with the objective being maintaining the original dimensions, so to speak, of the rice grain.

Several breweries in Hiroshima cooperated with Satake to brew sake that were identical in every way other than one being milled using Henpei Seimai and the other using the newfangled Genkei Seimai. One of them was Imada Shuzo, brewers of Fukucho. The owner/toji, Ms. Miho Imada, sent me a bottle of each to do the comparison.

In truth, I only had one bottle of each, and both were freshly pressed and nama. While certainly delicious, I might be able to tell a bit more with some time in the bottle and pasteurization, but that chance will come in time. And from what I tasted, the results were as subtle as might be expected considering how slight the differences in milling are.

The Genkei Seimai sake seemed sharper and brighter in aromas, but more settled, broader and rounder in flavor. The Henpei Seimai  seemed richer in aromas but lighter in flavor. While I am not sure why the aromas were that way, knowing that Henpei was brewed with rice with a bit less fat and protein, the slightly slimmer flavor seemed appropriate. But again, we would need another hundred samples or so to come up with a truly dependable result.

seemed richer in aromas but lighter in flavor. While I am not sure why the aromas were that way, knowing that Henpei was brewed with rice with a bit less fat and protein, the slightly slimmer flavor seemed appropriate. But again, we would need another hundred samples or so to come up with a truly dependable result.

After having brewed with all three types of milled rice, regular, Henpei and Genkei, Ms. Imada emphasized one thing quite emphatically.

“None of these methods is unequivocally better than the other. None will replace the other two; they all have their place. It depends on what kind of sake you want to brew; that’s the deciding factor.”

And, as mentioned above, to me what is most important is that these developments continue to take place, and that important companies like Satake continue be involved at the research and product development levels.

If you are in Japan, you can purchase both sake here and compare for yourself: https://fukucho.info/?mode=cate&cbid=2467869&csid=0

If you are interested the machine that does it, you can see the specs here, in Japanese: https://satake-japan.co.jp/products/ricemill/sake/edb40a.html

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Interested in learning more about sake, and the industry in Japan that makes it? Subscribe to Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Learn more and read a few sample issues here.