How old is the current sake industry? How long have most of the currently active sake breweries been around? Not surprisingly, there are several ways to look at it. But let’s try to get a concise view of the industry as it is today, bearing in mind that it is in a constant state of flux and change.

How old is the current sake industry? How long have most of the currently active sake breweries been around? Not surprisingly, there are several ways to look at it. But let’s try to get a concise view of the industry as it is today, bearing in mind that it is in a constant state of flux and change.

There are currently about 1200 sakagura, or sake breweries, active in Japan. About. It really depends on how you count them, and who is doing the counting. There are about 1200 that are active; however, amongst those, there are perhaps a couple hundred that just buy product brewed elsewhere and sell it as their own. (This way of doing things call for an article of its own, so we’ll save the explanation for that.)

Also, there are a couple hundred or so that have licenses but are inactive. And, there are a couple of bottling companies that legally must have a license too, but do not brew. So including them would bolster the number as well. And there are companies with multiple licenses, and some companies that brew but not every single year, and a handful of other statistic sticklers on top of that.

But to simplify things, there are about 1200 active sakagura in Japan now. How long have most of them been around?

Before answering that, we need to point out that the statistics are grouped by era in Japan. Sure, we could transcribe all those to western years, but that’s no fun. So firstly let us look at era names in Japan.

Basically, eras are named after the emperor that reigned in the respective time frame. But sometimes, chunks of time are named for  political eras. For example, the Edo era ran from 1604 to 1868, and was named after the capital city, Edo, which later was renamed Tokyo. This span of 264 years was one of relative stability as it was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, a long string of shogun that basically handed power down from father to son.

political eras. For example, the Edo era ran from 1604 to 1868, and was named after the capital city, Edo, which later was renamed Tokyo. This span of 264 years was one of relative stability as it was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, a long string of shogun that basically handed power down from father to son.

Within that 264 years there were several emperors, and the eras within the Edo era are also known by their imperial names as well. But the main point here is that the Edo era is something that is commonly referred to in Japan, but before and in particular after that eras are named for the emperor that reigned then.

So let us look at how many sake breweries that are still active today were founded in each of these eras.

Pre-Edo (before proper records were kept): 14

Edo era (1604-1868): 399

Meiji era (1868-1912): 431

Taisho era (1912-1926): 119

Showa era (1926-1989): 266

Heisei era (1989- April 30, 2019): 25

Reiwa era, the current era, which began May 1: 0

This means there are 431 companies founded between 1868 and 1912 that are still making sake, and 399 that were founded sometime between 1604 and 1868 that are still active as well. That’s some serious longevity.

There are reasons behind some of the above statistics. For example, in the Meiji era, tax from sake was the largest source of the government’s revenue, since personal income tax did not yet exist. And Japan was involved in a couple of wars back then, with Russia and China. So the government actually went to companies that made shoyu (soy sauce) – since they already had big tanks and lots of space – and directly requested that they begin to brew sake as well. This is one reason for the large number of breweries founded in that era.

In fact, although the short listing above does not show it, there are 903 active sakagura in Japan that are over a hundred years old. That means that 72 percent of the industry is a century old or more.

Back in 1988 there were about 2500 breweries, and before the war they numbered over 5000 spread across Japan. Clearly, many more have closed down over the years than have remained active. It is not possible to know how old each of them were when they closed down, of course, but chances are they some of the older breweries of their time.

The industry loses a couple of breweries each year. That rate of attrition seems to be slowing, i.e. we lost many more each year in the decades of the second half of the 20th century. But things are still contracting.

Yet looked at another way, the sake industry is one of remarkable durability and endurance. Let’s do our best to help that continue on for a few centuries more.

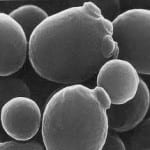

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake.

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake. One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.)

One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.) That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.

That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.