The answer: Yes.

T he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances.

One major enigmatic part of the sake world is rice, or more specifically, the importance of using proper, high quality sake rice rather than just regular sake rice – or even table rice – in making good sake. According to some folks, the choice of rice strain determines everything about a sake. Some brewers insist on using only one variety, or just a few.

Then there are those that say technique and brewing methods are more important than the choice of rice in determining the nature of  the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role?

the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role?

Rather than the folly of attempting to answer that – an exercise in futility of there ever was one – let me instead be part of the problem and actually support the paradox by showing an extreme example of each of these facets of the jewel that sake is. While this approach may not be so helpful in ultimately understanding sake, it may help encourage us to stop even trying, and just enjoy it.

So let us first look at this idea: to make the best sake, one needs to start with the best rice available. This would be easier to state if there was such a thing as “the” unequivocally best sake. But there ain’t. So let us lower our expectations just out of the gate and say that to make really good sake you have to start with really good sake rice.

Often but not always this means Yamada Nishiki. It has all the necessary qualifications in that it is easy to work with and easy for brewers to bend to their will. It behaves. Of course, it is not the only game in town, and there are brewers that do not use it at all. But a ridiculously high percentage of breweries use at least some Yamada Nishiki.

So Yamada is good. But there is good Yamada Nishiki, and there is great Yamada Nishiki. There is a ranking system, used predominantly in Hyogo Prefecture where the best Yamada grows. And there are microclimates and even particular rice fields in which the best Yamada Nishiki is harvested, measured by objective and measurable standards.

And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone.

And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone.

But then there’s the rest of the story…

There are also breweries that can make extremely enjoyable sake using less than stellar rice. Traditional techniques combined with modern measurement and technology help brewers tweak things to the point where they can maximize some things during production and minimize undesirables at the same time.

There is a brewery of which I am fond that is located in western Japan. It is quite popular and well distributed these days, and while the company is growing steadily, they are far from huge. I’ll hold back on naming it as the below might not be public information. The toji there is very regimented, and is not emotionally attached to traditional techniques, or at least not just because “that’s the way it’s always been done.” He uses plenty of machines, and eschews some steps that other toji consider indispensable.

After a recent visit to the kura, I was tasting through the lineup with the toji (master brewer) and the kuramoto (the owner of the  company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy.

company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy.

“Too much information, like grades and seimai-buai and all that, is distracting in our opinion. Sake should be judged on how it tastes and smells, and not much else. So we do not hide this information, but we deliberately downplay it,” they explained.

This attitude is slowly taking root, with more and more brewers releasing products with that kind of minimalist labeling. While there are admittedly few such product on the market right now, I expect it to grow to trend-like proportions over the next few years.

“Also, you’ll notice we do not put the name of the rice on the bottle either,” continued the kuramoto. “And that is deliberate too.”

“We brew almost all year-round here. And this product,” he said, hoisting a 1.8 liter bottle of their best-selling junmai ginjo, “is made from Yamada Nishiki. Basically. The thing is, we can’t always procure it for a full 12 months; there are years where there is not enough to go around. So once in a while, we have to use a different rice in a couple of batches.”

“So the truth is, I don’t know what rice is in there. There is an extremely high probability that it is Yamada, but I just don’t know for sure!” He exuded complete confidence in their way of doing things.

While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

So yeah, great rice is important. Unless it isn’t.

In truth, this conversation could go on forever. It could easily wax philosophical. Some would argue that you need that top-grade rice to make top-grade sake, and even for exorbitant prices there is a market for it. And such sake is outstanding. But is it certainly is not the most fitting tipple for all occasions; no way. Glitter. Glam. Bling. And we all like glitter, glam and bling once in a while, this guy included.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Announcing the launch of a new sake publication, Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Free until December 1! Subscribe before then and enjoy an 20% discount for ever. Learn more here.

The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider.

The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider. But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries.

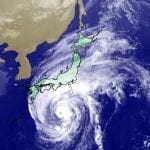

But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries. Surely modern technology in all areas helps this. For example, weather radar lenabled everyone to see the massive typhoon Hagibis that engulfed Japan in early October. This allowed the farmers growing Yamada Nishiki to quickly harvest the rice – albeit a bit earlier than they would normally have done it. An early harvest is much better than a ruined one. More significantly, though, climate change affects things in ways beyond higher temperatures.

Surely modern technology in all areas helps this. For example, weather radar lenabled everyone to see the massive typhoon Hagibis that engulfed Japan in early October. This allowed the farmers growing Yamada Nishiki to quickly harvest the rice – albeit a bit earlier than they would normally have done it. An early harvest is much better than a ruined one. More significantly, though, climate change affects things in ways beyond higher temperatures. Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

The brewing season – the first one of the new Reiwa era in Japan – has just begun. Most places have a tank or two, maybe more, already fermenting away. The fall is also the season for lots of tasting events of all kinds of groups and of various scales.

The brewing season – the first one of the new Reiwa era in Japan – has just begun. Most places have a tank or two, maybe more, already fermenting away. The fall is also the season for lots of tasting events of all kinds of groups and of various scales. Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended.

Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended. Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product.

Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product.