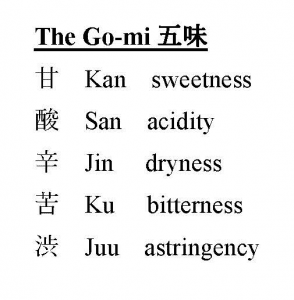

Limited to only the five “Go-mi” terms

Describing the flavors and aromas of sake can be a challenge. It doesn’t have to be, but often we make it so. In the end, if we like it then we like it. No descriptors are necessary if it is just for ourselves.

Describing the flavors and aromas of sake can be a challenge. It doesn’t have to be, but often we make it so. In the end, if we like it then we like it. No descriptors are necessary if it is just for ourselves.

However, if we want to convey the appeal of a sake, how it tastes and smells, and what makes it special and different from other sake, then we need words and descriptors that people can more or less agree upon.

And these days there are lots of resources available for this kind of thing. Some organizations have lists of terms to which students should try to limit themselves to ensure that people are using the same words, which is surely one effective strategy. Flavor and aroma wheels are available too from a range of people and sources.

All are useful! And terms like this are more important to some than to others, for sure. On top of that, there are plenty of folks that rely upon their own lexicon developed through years of experience, and furthermore, there are people that are not really interested in concrete descriptors. But in the end, it is better to have them than to be caught short on words – or to be inconsistent – when the occasion calls for it. Such terminology gives those with experience something to say, and those without it a foothold from which to ascend.

But not so long ago, sake professionals in Japan did not have such – or need – such an arsenal of expression. Remember that long ago, people drank what was local. And “I like it” was often synonymous with “it’s all I can get ‘cuz it’s all they sell near me!” Furthermore, back then there was far less varieties of sake from which to choose. The local brewery to which one might be limited could have three or four products – only!

The sheer variety of sake available these days from any one brewery is mind boggling compared to what it might have been as recently as 50 years ago. So for a plethora of reasons, flavor wheels and official lexicons simply were not necessary. But today, they are. And we have them! And fortunately, we also have legions of sake fans and professionals that are willing to at least try to express sake flavors and aromas in concrete words.

50 years ago. So for a plethora of reasons, flavor wheels and official lexicons simply were not necessary. But today, they are. And we have them! And fortunately, we also have legions of sake fans and professionals that are willing to at least try to express sake flavors and aromas in concrete words.

So, what terminology did they use long ago? How did sake pros talk to each other before we had so many varieties of sake and before modern infrastructure made the de facto market for any brewer much broader than the local yokels?

Five terms. That’s what they had; that’s it. Limiting things in that way is either extremely streamlined or needlessly restrictive. But worked for centuries for the sake industry, so there must be some merit to it!

So what are those five terms? Avoiding a long linguistic discussion on characters and their possible multiple readings, the five flavors are as below.

That’s it! Sweet, dry, acid, bitter, astringent. The are collectively referred to as the go-mi, or “the five flavors.” Long ago when judges would assess a sake, they would look for these five facets amidst the flavors and aromas, and importantly, the balance between them. All must be present; none can stand out from the others too much. It is certainly a very interesting concept, and brutally simple as well.

That’s it! Sweet, dry, acid, bitter, astringent. The are collectively referred to as the go-mi, or “the five flavors.” Long ago when judges would assess a sake, they would look for these five facets amidst the flavors and aromas, and importantly, the balance between them. All must be present; none can stand out from the others too much. It is certainly a very interesting concept, and brutally simple as well.

It also has its shortcomings. For example, to many people, sweetness and dryness are two sides of the same coin, are they not? And astringency is not an everyday concept in the West, although it is used much more in Japan. Furthermore, it overlaps with acidity somewhat.

Imperfections notwithstanding, limiting things in this way does provide some focus. But it surely makes it harder to convey to others what a sake actually tastes and smells like.

Of course, this discussion is admittedly laced with a healthy dose of hyperbole. In other words, even in the old days, surely people used more than five words to describe their sake, and to convey it. The use of these was probably limited to technical assessments and professional judges. Also, while these days no one “on the street” assesses sake this way, even these days there are still some older kuramoto and toji that settle down into this focused approach when seriously tasting sake.

As a side note, when normal people talk to each other about sake, rather than the five single syllable readings written above, we say amai (sweet), sanmi (acidity), karai (dry), nigai (bitter), and shibumi (astringency). You are much more likely to hear these words in a conversation.

In truth, these five terms are close to being relegated to a historical anecdote. But at the same time it is important to remember how things were done for so long, especially something that worked so well and for so many. And at the same time, to convey the wonders and appeal of sake to the world at large, modern terminology and expression is key. Like everything related to sake, including the go-mi, balance is key.

The 2nd Sake Professional Course Live Online, October 2020

On October 3, 4, 10, 11, 17 and 18 I will be running the second Sake Professional Course Live Online, to be held via Zoom on those five consecutive weekend days. The seminar will be run from Japan at a strategically selected time so that viewers in other parts of the world can watch it as well.

On October 3, 4, 10, 11, 17 and 18 I will be running the second Sake Professional Course Live Online, to be held via Zoom on those five consecutive weekend days. The seminar will be run from Japan at a strategically selected time so that viewers in other parts of the world can watch it as well.

The content of the course will be identical to the live, in-person Sake Professional Course, and the exam for Certified Sake Professional will take place online as well on October 24. We will run optional sake tastings at the end of each session, for those that want to purchase the sake. In truth, a handful of details are not yet set, and in fact Sake World newsletter readers are the first to know about this!

Learn more and download more information here. If interested, please send me an email, and I will get back to you as soon as the details are settled.

“No Sake Stone Remains Left Unturned!”