This article was originally published in Sake Industry News #57 Each issue of SIN has a handful of current news stories and reports, and one technical article written by John Gauntner. It is published on the 1st and the 15th of each month, and includes an audio version of the content as well. A one-year subscription is US$100, or US$10 a month. Subscribe with no risk, since your first two issues are free, and you can cancel with no obligation. Learn more and subscribe here.

This article was originally published in Sake Industry News #57 Each issue of SIN has a handful of current news stories and reports, and one technical article written by John Gauntner. It is published on the 1st and the 15th of each month, and includes an audio version of the content as well. A one-year subscription is US$100, or US$10 a month. Subscribe with no risk, since your first two issues are free, and you can cancel with no obligation. Learn more and subscribe here.

Like just about anything, it is quite possible to geek out with sake terminology. There are both academic and fun ways to describe any aspect of sake, including flavors and aromas. You can describe an aroma as bananas, or as isoamyl acetate. While certain situations might dictate that one or the other is more appropriate, often it is just a matter of one’s erudition threshold.

Those that work with sake and taste it regularly probably favor the techno-jargon, and for better or for worse I include myself in that number.

As time passes and sake evolves and changes, different aromas become more commonly encountered than they have been in the past, and accordingly so does the terminology used to describe them. Looking back perhaps 40 years, when ginjō styles began to become available to consumers, banana aromas (isoamyl acetate) was likely one of the first on the scene, although aromas clearly representative of the grapefruit–nail polish remover– airplane glue continuum (ethyl acetate) were commonly found in sake before that. They were found mostly in sake of the junmai variety, even if no one bothered to call ‘em out.

Then in the late 90’s or so, sake with apple and licorice aromas (ethyl caproate) became trendy in at least the ginjō realms, and much daiginjō remains that way today. As such, ethyl caproate is a commonly heard descriptor. Or, you could just say “apple” or “licorice.” Whatever floats your boat; but I digress.

But as brewers began to experiment with less commonly used yeast strains and kōji mold strains, a couple of new compounds have become a part of the sake description lexicon. These are not really new, having been around for eons in beer and wine, but maybe just recently have they become “a thing” in sake.

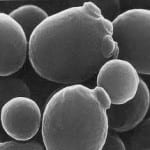

One of those if called 4VG, or 4-vinyl-guaiacol, and it’s a chemical compound (more properly, an aromatic monomeric phenol; got all that?) that arises when enzymes from the kōji decompose ferulic acid in the cell walls of the rice, or from wild yeast activity (got that part too?) .

For us mortals? It gives spicy clove-like or vanilla-esque aromas. It’s the same stuff that gives wheat beer its unique pungent aromas. In truth, though, it tends to be considered a fault, and so it is not that commonly encountered in sake, not nearly as often as the grapefruit-banana-apple triumvirate.

But describing it is important in the progression to presenting 4MMP.

What is 4MMP? First of all, it’s more formally known as 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one. While it sounds like a member of the X-Men series, it’s actually a chemical compound that has become increasingly found in moderately ostentatious sake, like that submitted to contests, or brewed to be impactful and aromatic. Some have called it the “third ginjō aroma,” with the first two being the aforementioned isoamyl acetate (banana) and ethyl caproate (apple-licorice).

What is 4MMP? First of all, it’s more formally known as 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one. While it sounds like a member of the X-Men series, it’s actually a chemical compound that has become increasingly found in moderately ostentatious sake, like that submitted to contests, or brewed to be impactful and aromatic. Some have called it the “third ginjō aroma,” with the first two being the aforementioned isoamyl acetate (banana) and ethyl caproate (apple-licorice).

Just how present it is in any sake depends on, among other things, the choice of kōji mold, yeast, and the fermentation temperature. And all this talk is on the cutting edge – the forefront – of sake geekdom.

Again, how would we mortals describe it? I would say white grape, or lychee, maybe with a citrus-laced backdrop. Others might say pineapple, or full-on citrus. Interestingly it is also found in lots of hops. One website upon which I stumbled that highlighted the sake of one particular prefecture literally said “cat piss,” but did not seem to consider it a fault. I admit I am having trouble finding common ground between that one and the others, so I’m sticking with my grape-lychee descriptor.

A 2019 report from the National Research Institute of Brewing that analyzed sake submitted to the “National New Sake Tasting Competition,” officially known as the Japan Sake Awards, found that sake with lots of 4MMP was overall appraised slightly lower, but that when present it enhanced fruity essences outside of the usual suspects of banana and apple. Wow. That alone makes it interesting in my book.

It’s still too early in the game to know how much this will affect sake trends in the coming years. Like many developments that make sake more ostentatious, it seems more popular among younger sake purveyors; it may fall by the wayside in time or it may become a bona fide trend. Either way, it is a fun new aspect of the ever-evolving sake world, and well worth checking out.

Do you work with sake? Or just interested beyond the basics?

Do you work with sake? Or just interested beyond the basics?

Then you need to be reading Sake Industry News.

Subscribe now and your first two issues – as well as access to all back issues (over 130 issues!) are free.

Check it out thoroughly, and then decide if you want to continue!

Learn more here !

Next Five was formed in 2010, and is a group of five brewers in Akita Prefecture whose stated objective is to discover what sake of the next generation will be, and to be leaders going into that. They do a number of promotional activities, focusing mainly on three things: sake tasting events, other social and artistic events around which sake can be enjoyed, and all gathering each year at one of the five breweries and working together to make one sake together, with each one of them taking on one of the indispensable roles in sake brewing each time. I have also read that their plan was to have each member step down as they get older and replace them with like-minded younger brewers so as to keep the spirit of the next generation alive, although I am not sure if that has actually taken place. From my perspective they are the most visible, at least until recently.

Next Five was formed in 2010, and is a group of five brewers in Akita Prefecture whose stated objective is to discover what sake of the next generation will be, and to be leaders going into that. They do a number of promotional activities, focusing mainly on three things: sake tasting events, other social and artistic events around which sake can be enjoyed, and all gathering each year at one of the five breweries and working together to make one sake together, with each one of them taking on one of the indispensable roles in sake brewing each time. I have also read that their plan was to have each member step down as they get older and replace them with like-minded younger brewers so as to keep the spirit of the next generation alive, although I am not sure if that has actually taken place. From my perspective they are the most visible, at least until recently.