Fall can be fun, but fall can be tiring. One sake tasting after another means so much other work does not get done. The traditional fall tasting season mercifully ends soon, but making the rounds is both important and fun.

Fall can be fun, but fall can be tiring. One sake tasting after another means so much other work does not get done. The traditional fall tasting season mercifully ends soon, but making the rounds is both important and fun.

One of the last for me this year was a tasting of Yamaguchi Prefecture sake. There are 28 or so breweries there, 20 of which gathered for the event. And as I am always reminded, tasting the sake is fun, but one can learn ten times as much from chatting with the brewers. Therein lies the value and appeal of these tastings.

And at the Yamaguchi tasting the other day I made my way round to the eponymous Taka, brewed by the company called Nagayama Honke. The owner/toji Taka Nagayama himself was there to pour and greet.

I know his stuff well and zipped through them, but the last one got my attention. It was a junmai daiginjo, but made with Tojo Yamada Nishiki. While not overly assertive in flavor, the breadth and the reverb permeating the overall flavor profile were outstanding – but not surprising. Afterall, it was Tojo Yamada.

Tojo was the former name of the village in which this outstanding rice is grown, but a spate of annexations saw the town itself become annexed into another one a few years ago. So even though the town of Tojo is long gone, the term Tojo Yamada Nishiki was safely trademarked, and good thing too.

Like any agricultural product, there are certain regions and even microclimates in which each strain of sake rice will thrive. And this of course applies to what is almost universally considered to be the best sake rice, Yamada Nishiki. This variety is grown in 33 of Japan’s 47 prefectures, but the overwhelming consensus is that it grows best in Hyogo Prefecture. And deep in the mountains of this prefecture, where the days are hot and the nights are cold, is a village formerly known as Tojo, and another village named Yokawa. And it is these two areas from which the best Yamada Nishiki comes. Tojo tends to command a higher price than Yokawa, but the latter is exceptional to be sure, especially in comparison to that rice grown in other regions.

And Taka, our sake-pouring owner-toji friend from the opening paragraph, lavished praise upon Tojo Yamada. “Yeah, you can’t really top it, can you! It’s as good as it gets, and the price of the rice reflects that. But I have done a good job of keeping the retail price as low as I can so folks can enjoy it.

“And,” he continued, “what is amazing is how well it stands up to time. It basically does not hineru,” he asserted. Hineru refers to a sake starting to taste old from, well, getting old. The difference between hineru and nice maturation is a fine line, of course, but I digress.

“Even Yokawa,” he continued without being prompted, “as good as it is, that will show maturity pretty quickly; but not Tojo. That’s why I think Yokawa Yamada Nishiki might be good for super premium sake bound for overseas markets – it will remain stable for a long time,” he concluded.

The point here is not that one should drink Tojo over Yokawa, or that one region is superior to another. Those are worthwhile discussions too. But rather, what is interesting is how fundamentally different the same strain of rice can be from two regions that are so close. Tojo and Yokawa are right next to each other. They are perhaps a couple of kilometers apart; that’s all. But the slight differences in the mineral makeup of the soil and of course minute climactic differences lead to the best and second best examples of the mighty Yamada Nishiki to be noticeably and consistently different.

different the same strain of rice can be from two regions that are so close. Tojo and Yokawa are right next to each other. They are perhaps a couple of kilometers apart; that’s all. But the slight differences in the mineral makeup of the soil and of course minute climactic differences lead to the best and second best examples of the mighty Yamada Nishiki to be noticeably and consistently different.

What is wild about this to me is that, yes, the choice of rice is connected to the final flavor profile of a sake. But that connection is not nearly as tight as the connection between the grape variety and the final flavor of the wine. Ten brewers can take the same rice, milled to the same degree, and make ten completely different sake. How the koji was made, the yeast used, the fermentation temperature and number of days, and how the sake was pressed and later handled all contribute huge differences.

Yet, in spite of all this, the basic nature of the rice will shine through, and that basic nature can be quite different on a subtle but measurable level, even for the same strain grown just a few kilometers apart.

Similar differences can, in fact, be demonstrated in other strains of rice from other parts of Japan. In fact, there are a handful of brewers now doing things like brewing sake using the rice of only one rice field, and not blending them, to make the most of the differences that invariably exist from one rice field to the next.

Surely these efforts will garner more attention as time goes on, although few will be as prominent as the tale of two Yamadas as told by Taka. It’s all fascinating stuff, and it all demonstrates how much there is to learn – and unlearn – about sake

* * *

Sake Professional Course

The next Sake Professional Course will be held in Las Vegas, Nevada on November 27 to 29. As of today, only three (3) seats remain open.

The next Sake Professional Course will be held in Las Vegas, Nevada on November 27 to 29. As of today, only three (3) seats remain open.

The content of this intensive sake course will be identical to that of the Sake Professional Course held each January in Japan. The course is recognized by the Sake Education Council, and those that complete it will be qualified to take the exam for Certified Sake Specialist, which will be offered on the evening of the last day of the course.

Learn more about the course here. You can read Testimonials from past participants here.

If you would like to make a reservation or to be placed on the notification list, please send an email to that purport to sakeguy@gol.com.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me. bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable.

bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable. Kijoushu

Kijoushu Mr. Naohiko Noguchi is one of the most decorated, respected, accomplished and famous toji (master brewers) in the history of the sake brewing industry. And at 84 years of age, he is coming out of retirement for the fourth time to brew sake at a new brewery starting up next month. At 84. That’s eighty-four. As in LXXXIV. As in “hachijuyon.” One would think enough is enough; not for some folks.

Mr. Naohiko Noguchi is one of the most decorated, respected, accomplished and famous toji (master brewers) in the history of the sake brewing industry. And at 84 years of age, he is coming out of retirement for the fourth time to brew sake at a new brewery starting up next month. At 84. That’s eighty-four. As in LXXXIV. As in “hachijuyon.” One would think enough is enough; not for some folks. In fact, a friend of mine actually worked under him for twelve years at Kikuhime. But it was another ten years after the time that Noguchi-san retired (uh, the first time) that he could actually speak directly to him. Even while toiling under his direction, their difference in hierarchical rank was so great that all communication had to go through someone else. Wow. (Nowadays, they actually hang out from time to time.)

In fact, a friend of mine actually worked under him for twelve years at Kikuhime. But it was another ten years after the time that Noguchi-san retired (uh, the first time) that he could actually speak directly to him. Even while toiling under his direction, their difference in hierarchical rank was so great that all communication had to go through someone else. Wow. (Nowadays, they actually hang out from time to time.) Brewer Number One stood up and faced the crowd. And he talked about his sake. Its lively yet balanced nature is the result of a family of yeasts, one of which was discovered at his brewery several decades ago, he explains. It has contributed to – if not created – the high reputation enjoyed by all of the sake in that region, which only came into sake prominence about 30 years ago.

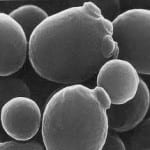

Brewer Number One stood up and faced the crowd. And he talked about his sake. Its lively yet balanced nature is the result of a family of yeasts, one of which was discovered at his brewery several decades ago, he explains. It has contributed to – if not created – the high reputation enjoyed by all of the sake in that region, which only came into sake prominence about 30 years ago. Yeast is massively important to the making of great sake. While they contribute to aromas more than anything else, good yeasts will also ferment strongly and not peter out too early, tolerate high levels of alcohol, yield appropriate levels of acidity that are not too high nor low, and much more.

Yeast is massively important to the making of great sake. While they contribute to aromas more than anything else, good yeasts will also ferment strongly and not peter out too early, tolerate high levels of alcohol, yield appropriate levels of acidity that are not too high nor low, and much more. Again, this really does not happen anymore; nor was it ever a huge industry problem. But I have heard about it from several brewers, elevating it above simple legend. Also, just getting a good yeast is not the end of the challenge. A brewer with any new yeast needs to learn its idiosyncrasies during preparation, throughout fermentation, and beyond.

Again, this really does not happen anymore; nor was it ever a huge industry problem. But I have heard about it from several brewers, elevating it above simple legend. Also, just getting a good yeast is not the end of the challenge. A brewer with any new yeast needs to learn its idiosyncrasies during preparation, throughout fermentation, and beyond.