Happy “Nihonshu no Hi,” or Sake Day!

October 1 of each year is officially designated “Nihonshu no Hi,” or “Sake Day.” But why October 1? Why not April 1? Or May 20, or any one of 364 other valid days?

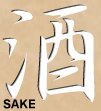

There are, not surprisingly, several reasons. However, the biggest reason is related to the  written character for sake.Long ago, it consisted of only the right half of its current form; in other words, the original form of the character for sake did not include the three short lines on the left side, which, by the way, represent water, or at least liquid.

written character for sake.Long ago, it consisted of only the right half of its current form; in other words, the original form of the character for sake did not include the three short lines on the left side, which, by the way, represent water, or at least liquid.

Rather, the original character for sake consisted only of the part that was made to look like a jar, indicating something holding liquid, which was of course an alcoholic beverage of some sort in the mind of those looking at the character.

Enter the Chinese zodiac: 12 animal signs that are traditionally used to number years in the traditionally accepted sequence. Long ago, by the way, it also was used to count two-hour periods in each 24-hour day.

Enter the Chinese zodiac: 12 animal signs that are traditionally used to number years in the traditionally accepted sequence. Long ago, by the way, it also was used to count two-hour periods in each 24-hour day.

The tenth of these is tori, or chicken (or perhaps rooster or cock). However, the written character assigned to each of these animals as used in the zodiac is not the standard characters used when referring to the animals in normal writing, but rather a special character and reading used only in these traditional Chinese zodiacal instances.

Also, one reading of this character is “toh,” which is a synonym for ten, a point that is of course tied in to the association of this particular character to the tenth hour, month and year in a cycle.

So, by fortuitous coincidence, the tenth year, hour and month, i.e. October are represented in the ancient Chinese zodiac system, also embraced by Japan, by the old character for sake. And, coincidentally, sake brewing begins in the fall, usually in October. And that is why the first day of the tenth month, October 1, is known as “Nihonshu no Hi,” or “Sake Day,” in Japan.

As with everything in the culture of sake, it is hardly random, yet hardly obvious. Therein lies its appeal.

The Sake Notebook – all you need to know about sake in a concise, enjoyably readable package! For Kindle. For Nook. For iPad. Downloadable pdf. Learn more here.

The Sake Notebook – all you need to know about sake in a concise, enjoyably readable package! For Kindle. For Nook. For iPad. Downloadable pdf. Learn more here.

Sake’s Hidden Stories – what the other sake textbooks don’t tell you.  Learn about the brewers behind the brew. For Kindle. For Nook. For iPad. Downloadable normal pdf. Learn more here.

Learn about the brewers behind the brew. For Kindle. For Nook. For iPad. Downloadable normal pdf. Learn more here.

Visit Sake World, learn all about sake, and sign up for a free newsletter here.