Although brewers have been working on making better and better sake for, heck, 900 years or so, the last century or so has been fairly exponential in terms of gains in sake-brewing methods and technology.

Although brewers have been working on making better and better sake for, heck, 900 years or so, the last century or so has been fairly exponential in terms of gains in sake-brewing methods and technology.

Even though we can say that, for many centuries, sake-brewing has remained basically the same, in fact there have been many changes. From just about 100 years ago, technology and science began to augment the well-entrenched experience and traditions of brewers.

Often, we hear that ginjo sake is leaps and bounds better than the sake of yesteryear, replete with complexity of flavor and fragrance that allow it to be appreciated as a such a premium beverage. Let’s look at some of the more significant contributions over the last century to what has become today’s sake.

1568: Brewers in Nara began to heat sake up to about 65C to “remove the evil humours,” thus pasteurizing and providing stability to sake. Louis Pasteur lent his name to this process centuries later, and he got all the credit.

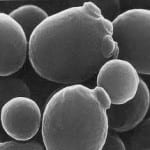

1895: Sake yeast was first isolated. Until this time, yeast cells were allowed to simply fall into the vat  from the ambient environment. Finally, brewers were able to see just what the yeast cells looked like, and to study their life cycle.

from the ambient environment. Finally, brewers were able to see just what the yeast cells looked like, and to study their life cycle.

1904: The Ministry of Finance forms the National Sake Brewing Research Center. Here, research geared toward helping producers make better sake continues to this day.

1910: Sokujo moto, the fast-starting yeast starter, is developed. Until this point, creating the moto yeast starter was a long, exhausting process and an extremely labor intensive part of sake brewing. When it is discovered that the result of the techniques was to create a bit of lactic acid, researchers found that putting a bit of pure lactic acid in at the beginning accomplished the same thing, saving significant labor and time.

1911: The first Shinshu Kanpyoukai, or New Sake Tasting Competition, was held. The longest-running competition of its kind in the world, this yearly tasting continues today and has driven major advances and trends in sake profiles over the years.

1923: Stainless steel tanks begin to replace traditional cedar tanks. As the woody flavor imparted by cedar tanks can be strong, sake brewed in stainless steel tanks is now free to express a myriad of new and delicate flavors, fragrances and nuances. This was huge.

1933: Modern vertical rice milling machines are introduced. The condition of the rice after milling “how  much it has been milled, how much heat was generated during milling, how many of the rice grains fractured or broke” affects every single step on down the line. With this major advance, rice could be polished more accurately, carefully, and efficiently. This was also extremely huge; it eventually led to the era of ginjo.

much it has been milled, how much heat was generated during milling, how many of the rice grains fractured or broke” affects every single step on down the line. With this major advance, rice could be polished more accurately, carefully, and efficiently. This was also extremely huge; it eventually led to the era of ginjo.

1936: The mighty Yamada Nishiki, the king of sake rice strains, is born. It is created as a cross breed between two other sake rice strains, Yamadaho and Wataribune. Although expensive and relatively hard to grow, Yamada Nishiki is the most widely used sake rice, especially when brewing ginjo-shu. There are other rice strains that make character-laden and wonderful sake, but Yamada has yet to be dethroned.

1943: The sake classification system of Special Class, First Class, and Second Class is created by the  Ministry of Finance. All sake is designated as one of these three, with First and Special classes requiring government tasting and certification, and (of course) higher taxes. This system is later abolished in 1989 for several reasons, one of them being that many brewers simply did not submit their sake for certification, thereby keeping prices of great sake lower. As such, the system lost much of its meaning.

Ministry of Finance. All sake is designated as one of these three, with First and Special classes requiring government tasting and certification, and (of course) higher taxes. This system is later abolished in 1989 for several reasons, one of them being that many brewers simply did not submit their sake for certification, thereby keeping prices of great sake lower. As such, the system lost much of its meaning.

Also in 1943, it became obligatory to add distilled alcohol to sake at the end of the brewing process. The obligation was removed in 1946, but brewers were not forced to stop this practice. This can enhance flavor and fragrance and stabilize the brew, but can also be used to simply produce cheaper sake.

1946: Yeast Number 7 is discovered and isolated by Masumi Brewery ofNagano. This yeast is still today the most used yeast in the country. That year, Masumi sake wins every single award in sight for their sake.

1953: Yeast Number 9 is discovered in Kumamoto Prefecture, by the brewers of Koro sake. Yeast Number 9 produces fragrant and fruity sake, with a decent acidity. It is today the most widely used yeast for ginjo-shu, although it has a lot of competition these days. A biggie on the flavor and fragrance fronts.

1968: The first post-war junmai-shu (sake brewed with no added distilled alcohol, nor any additives of any kind) is brewed. Although two brewers, one in Kyoto and one in Kumamoto, claim to have done it first, it marks a move of great significance (i.e. a biggie) by members of the brewing world toward quality and better sake, and profit margins be damned.

1974: National sake production hits an all-time high. Unfortunately, since that point it has been mostly downhill, with production volume decreasing almost every year since then.

1975: The Jizake boom begins. Jizake is a vague term that means sake from smaller brewers in the countryside, or at least sake not from large national brands. Such sake began to gain popularity for its supposed character and regional distinction.

1981: The Ginjo boom begins. Premium sake begins to increase in both popularity and production from this point. Even today, while overall sake production declines, ginjo-shu production increases, albeit by very little.

1989-2015: Dozens of new strains of yeast and new sake rice strains are developed and come into use in sake brewing. Many of these are proprietary, and many are kept within the prefecture of origin. These factors alone contribute to a new and wide range of sake profiles.

All of the above have built upon each other to create sake as it is today. But modern equipment and microbiology alone could not have led to the ambrosia that is the sake of this era. Just as much credit must be given to the craftsmen and craftswomen, and their decades of accumulated skill and refined senses. Indeed, their craft deserves much appreciation!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Only about five seats remain open for Sake Professional Course Chicago 2016, March 28~30. Learn more here, and contact me if you are interested in attending.

Only about five seats remain open for Sake Professional Course Chicago 2016, March 28~30. Learn more here, and contact me if you are interested in attending.