Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

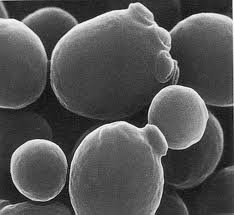

The three main ingredients of sake are usually given as water, rice and koji, which is steamed rice with a mold grown upon it that converts starch to sugar. But although not usually listed as an ingredient, yeast is crucial in that it converts that sugar into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and many other things that make a sake taste and smell the way it does.

Yeast does and will occur naturally in the environment, but is – with only a couple of exceptions – manually added. More than anything else the choice of yeast determines the aromas of the final sake, although as we have come to expect with sake, it ain’t quite that simple.

There are hundreds if not thousands of yeasts used in sake brewing today.

Tons of ‘em. Oodles and oodles of ‘em. I am fond of saying that “everybody and his brother has a proprietary or special yeast.” Many (if not most) of them are recently developed and are to some degree experimental; if the resulting sake is a hit, great. If not, the brewer may move on to other yeast choices. As such, many are not long for this world. Indeed, few will last the test of time.

Not that it has always been this way. The surge in proprietary and specially developed yeast strains is about 25 years old now, I reckon. Before that the  industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

Where do they come from? With so many out there, obviously there must be multiple sources. But it is probably safe to say that most sake in Japan is made using a yeast obtained from the Nippon Jozo Kyokai, known officially in English as the Brewing Society of Japan.

The “BSJ” has been around since 1906, originally as a group of researchers that had recently graduated from a governmental sake production course.

Their main functions are R&D, and of course stocking and distributing microorganisms, mainly sake yeast. The yeast strains themselves were for the most part discovered in sake breweries around Japan, and most have been around for decades and decades.

They are meticulously reproduced and kept pure year after year, providing stable and dependable fermentation to sake breweries all over Japan. While yeasts can have all kinds of names, those from the BSJ are recognizable by their very simple nomenclature, such as #6, #7, and #9 – which belie their significance in the industry.

While numbers one to five do exist, they are no longer distributed due to what is considered to be excessive acidity. In fact, amongst the handful of yeast strains that are actively supplied, the main ones to remember are numbers 6, 7, 9, 14 and 18-01. They were named in order of discovery, and the higher the number, the more ostentatious the aromatics. (Sorta. It’s not quite that simple, but for sound-byte purposes, that’ll do in a pinch.)

In terms of how these are reproduced, it varies a bit from yeast to yeast. But basically, stock yeast cells are put into an environment that encourages reproduction. Kind of like a love hotel for yeast, I guess. The resulting yeast cells are harvested, and washed with sterilized water, analyzed for purity and quality, and then bottled in little glass ampules.

In terms of how these are reproduced, it varies a bit from yeast to yeast. But basically, stock yeast cells are put into an environment that encourages reproduction. Kind of like a love hotel for yeast, I guess. The resulting yeast cells are harvested, and washed with sterilized water, analyzed for purity and quality, and then bottled in little glass ampules.

Yeast cells mutate very quickly, and so the cells must be checked to be sure

the compounds they produce and the other characteristics are true to the original. Otherwise the acids, esters and alcohols could change, and brewers would end up with sake that is totally different from what was sought.

Once these ampules arrive at the kura, brewers will then use them by pouring the pure yeast directly into a yeast starter, or alternatively, giving the yeast cells a kick-start via a nutrient solution of koji and water. There are also other ways, of course.

However, as alluded to above, the BSJ is not the only source of yeast. Far from it! Many prefectures have their own research organizations that develop yeast strains for use by local breweries, and many breweries have their own proprietary strains as well. “Developing” yeasts really means isolating them from amongst countless strains naturally occurring in the air. (No genetic modification is done at all.)

But for almost all of these modern yeast types, rather than being a yeast that rose naturally to the top both literally and figuratively, they were the result of an active search for particular qualities like fruity aromas. Certainly there is nothing wrong with this; it is still a natural process. But many of these more modern yeast type are comparatively ostentatious in their aromatic profiles, with apple and licorice and tropical fruit more apparent than the banana and melon of olde.

Furthermore, many of these new whippersnappers amongst the ranks of yeast do not tolerate time well, in other words, the sake made using them changes comparatively quickly in the bottle, sometimes leading to bitterness in the background of the sake.

This is not to discredit or criticize their use, nor the sake to which they lead. Much of it is wonderful and popular, to be sure. The only point here is to highlight some of the differences.

However: it does seem to be that the modern yeasts, for all their lively aromatics, are very slowly falling out of favor. Perhaps a more correct way to say that is that there seems to be a slow but evident return to the more classic yeast types, in particular #6, #7 and #9, with a dollop of #14 in the daiginjo department.

Is this clearly measurable? Nah; not yet. It is still a fledgling trend. And it may not gather critical mass, and the tendency to use modern yeasts may continue. As such, not much is clear on the yeastern front at all. Vibrant ginjo aromas are still popular, even if less pretentious sake does seem to be making a comeback.

It is important to emphasize again that there is no one superior yeast or group of yeasts. As long as the sake is enjoyable by a significant number of people, anything goes. “It’s all good,” as they say. But the slight trend toward the classics, both in terms of aromas, choice of yeast, and brewing methods such as kimoto that tie in well with more less brazen yeasts, is interesting to observe.

More and more producers are providing yeast information for the sake available both in Japan and overseas. Be sure to take note of this information – and your own observations – as you enjoy sake from here on out. It can only enhance your sake experiences.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Learn more here.