What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty.

What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty.

But what if we take a step or two back, and from a simple ingredients-to-results point of view ask “why’s it taste and smell like that? What makes it sweet or dry or rich or thin or fruity are ricey or sharp or round?”

Again: we could get technical. But in truth, a caveat-augmented simple explanation is more than enough. In other words, we can present the most general reasoning, the one that represents 70 percent of the truth, and then acknowledge that the remaining 30 percent exists as exceptions.

So let us look at what affects the way a sake tastes, smells and otherwise presents itself to us. The sources of those elements will be one of three things: ingredients, brewing methods, and after-care, or post-brewing handling methods. While there are countless ways of assessing the nature of sake, let’s narrow it down to those three.

And breaking it down further, let the ingredients be narrowed down to rice, water, koji and yeast.  (Actually, since those are the extent of sake’s ingredients, that ain’t really narrowing it down, but you know…) And let us consider the following steps as the brewing methods that affect the nature of the sake: milling, yeast starter methods, pressing methods, pasteurization, whether or not alcohol has been added (i.e. whether or not it is a junmai style) and aging.

(Actually, since those are the extent of sake’s ingredients, that ain’t really narrowing it down, but you know…) And let us consider the following steps as the brewing methods that affect the nature of the sake: milling, yeast starter methods, pressing methods, pasteurization, whether or not alcohol has been added (i.e. whether or not it is a junmai style) and aging.

And finally, (But wait, there’s more!) we have region and final specs like the nihonshu-do (or SMV) and acidity. While these are more results than causes, we can extract info from them.

Since this is far too much for one enjoyable reading session, let us approach this over a couple of newsletters, and let us start this time with the basic ingredients of sake: rice, water, koji and yeast. And breaking it down to its most welcoming presentation, it might look like this.

I. Rice = Flavor

I. Rice = Flavor

In short, rice affects flavor. But rice affects more than just flavor – umami and mouth feel for example. And other things affect flavor other than rice. But more than anything else, the choice of rice affects flavor.

There are about 400 types of short grain “Japonica” rice grown in Japan, and about 100 of the are sake rice types. While not all are distinctive in the flavors they provide, many are. Bear in mind that the rice-to-final-sake connection is not nearly as tight as the grape-to-final-wine connection. Much more affects the sake along its evolution in the kura. But the connection is still an important one.

Some rice will give sake balance and fullness, others will indeed affect specific flavors like sweetness or characters like acidity. Some lead to broader mouthfeels while others are much more narrow in their unfolding. And some lead to no discernible qualities other than lightness.

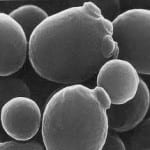

II. Yeast = Aroma

II. Yeast = Aroma

In short, yeast affects aromas. But yeast affects more than just aromas – acidity and alcohol for example. And other things affect aromas other than yeast. But more than anything else, the choice of yeast affects aromas.

Do you smell melon? It’s due to the yeast. Banana? That would be yet another yeast. Apple and licorice? That is from yet another family of yeast strains. Is it entirely this simple? Oh, God no. But basically, aromas are a result of the choice of yeast.

III. Koji = sweetness/dryness and umami.

In short, the way the koji is made will affect how sweet or dry the sake will be. Also, since the higher the ratio of koji to plain steamed rice, the more the amino acids, the more umami the sake will have.

But koji affects more than just sweetness and umami. And other things affect sweetness and umai. But more than anything else, koji affects sweetness/dryness and umami.

Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

Also, the more koji that goes into the batch, the richer and fuller the sake will be, expressed in terms of umami, that sixth taste, the concept of which is becoming much more familiar to the world at large.

Of course, koji leads to other aspects of the sake, and if not created properly can lead to faults as well. But basically, sweet-or-dry and umami are tied to koji.

IV. Water = mouth feel.

In short, the water – and in particular the mineral content of the water – affects mouth feel. But water affects more than just mouth feel – like how vigorous or lackadaisacal the fermentation proceeds. And other things affect mouth feel besides the source of water. But more than anything else, water affects mouth feel.

Soft water yields a softer, more absorbing mouth feel, and is actually more suited to ginjo production as well. Harder water often leads to a fuller mouth feel with a quicker finish.

Men at Work at Rihaku Brewery

As alluded to above, there is much more that affects how the sake ends up. Just how the ingredients are coaxed and guided during the brewing process is the next phase of all this. We will look at that next month, but for now, remember that rice leads to flavor, yeast yields aromas, koji leads to sweetness or dryness, as well as umami, and water leads to mouth feel. Basically. Sort of.

It all rests comfortably in the vagueness of all that sake is. Fortunately, we need deal with none of this to enjoy it.