In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter.

“It’s a private club,” they were told. “You have to leave, you have to leave.”

“But we want nothing more than to have a drink in your fine establishment, sir. We mean to cause no trouble,” came the response.

“Fine,” they were told by the semi-philosophical owner. “You are free to have a drink.”

Well, not five seconds after getting beer in hand, the bar exploded into pandemonium, with the bikers  shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

Immediately, as if on cue, a dozen or so club-wielding affiliate members poured out of the back room and exacted justice.

“Now youse can’t leave.” The movie, as good as it was, has been relegated to the attics of my mind, save for that one line. “Now youse can’t leave.” And so it is with some of my sake.

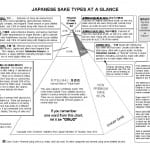

Backing gingerly back into the realm of sake-talk, we are often told “the rules” of sake care and such, but it is very important to remember that in the world of sake there are countless exceptions to every rule. One of those is the rule of drinking your sake young. Sure, it is true that almost all sake is meant to be consumed young, and that traditionally and historically it has always been done so (again, with some exceptions notwithstanding).

Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.

Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.

The fact is that well matured sake can be very interesting, if you are into it, if you are open minded about what constitutes good, and if you have a sense of humor (for those inevitable mis-judgements).

There are several vaults for sake in my office, some cold, some not. Over the course of time, the nature of my work dictates that many a bottle finds its way to me. Try as I might (and oh, I do try), I cannot drink them all in a timely manner. So I often find myself peering into a three-level storage bin six bottles deep and as many wide, pondering what has to go next. And inevitably, I will find one or two that I feel should be tasted soon or they could potentially begin that long, slow, downhill slide.

But one of the great joys of this process is to find one or two that definitely should have been consumed a couple of months earlier. And if I think they can stand up to it, I look at ‘em and say with a forced sinister smile, “Now youse can’t leave.” And I deliberately lay them down for months or more, knowing full well the risk I am taking in doing so. Sometimes I am pleased with the results; other times I just tell myself that I am.

My point is decidedly not to suggest you indiscriminately leave your sake laying around. Rather, I simply want to point out that the world of aged sake does in fact exist. While it may be a small percentage of all sake made, and while few brewers make it, and even fewer apply an organized approach to producing it regularly, it can be a fascinating part of the sake world.

Aged sake is not unequivocally better, nor any more special, and in general only commands slightly higher prices. It is not really collectible and does not increase with value. And like most of us, it does not much resemble what it was in its youth. However, aged sake is in fact very interesting and worth checking out whenever you might come across it.

Tanks of sake awaiting perfect maturity

Should you come across an aged sake, by all means try it. Should you find one that has been forgotten, or one to which you did not get around to drinking after purchasing it years ago, do not despair! Lower your expectations, raise your sense of humor, and try it. You may be very pleased with the results, and if not, you have gained a useful education on how sake ages.

Such are the idiosyncrasies of the sometimes frustrating, often-times interesting, always one-step-ahead-of-human-intellect world of sake.

This kind of vagueness does not stop at aging sake; it keeps us all guessing at every step. After a certain period of time, after crossing a vague threshold of sake understanding, we become so interested in sake’s intricacies and exceptions that even if we wanted to stop studying it, we find we cannot.

This is the point in time when sake itself looks us all in the eye and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

****************************************************************************************

Three holiday sake gift ideas:

(1) A subscription to the magazine Sake Today http://ow.ly/VOYWi

(2) the book Sake Confidential http://ow.ly/VOZ24

(3) the 99-cent app The Sake Dictionary http://ow.ly/VOZ6c

The only question is, how much do you – or that special someone – want to read?