The sake brewing process is a fairly intricate, convoluted affair that sounds complicated at first listen, and only gets more so as one gets deeper into it. And that is precisely the appeal of sake: you’ll never know it all. If one were to streamline the explanation so as to convey it in just a few sentences, it might sound like the below. While it is a super simplification, it is enough to lay the foundation for the topic here.

The sake brewing process is a fairly intricate, convoluted affair that sounds complicated at first listen, and only gets more so as one gets deeper into it. And that is precisely the appeal of sake: you’ll never know it all. If one were to streamline the explanation so as to convey it in just a few sentences, it might sound like the below. While it is a super simplification, it is enough to lay the foundation for the topic here.

“To make sake, a yeast starter that has a very high concentration of yeast must first be created so as to allow the subsequent fermentation to continue unfazed by all the stray micro-organisms dropping in for a visit. But to get sugar to feed that yeast, some of the rice must be inoculated with a mold, koji mold, that provides enzymes and breaks down starch molecules to glucose.

“After the yeast starter is adequately prepared, the size of the batch is essentially double three times over four days by adding more rice, moldy rice, and water, with the purpose of dividing it up into three separate additions being to keep the yeast population high and strong. After the 20- to 30-day fermentation period, the remaining rice solids are filtered out through a press to yield clear sake.”

There you have it, in all of its tradition-insulting oversimplifying glory. What we have at this point is undeniably sake. But if the explanation of the process were drawn out over several pages, it would likely be then suffixed by something akin to, “oh, then, you might charcoal filter it, you might pasteurize it, store it, cut it with water, maybe pasteurize it again, bottle it, and ship it.” This makes it sound as if once fermentation is completed and you have “sake”, the rest is a simple matter of course, and not much to be concerned about. But, as you may have surmised, it is not that simple. Sake never is.

Without a doubt, the “after it’s sake” processing has just as much to do with the nature of the final product as does the complicated  brewing process before it. One brewer told me that he considers the last few steps, or “after-care” as he called it, to be about 51 percent of the quality of a sake, and the complicated pre-pressing steps only 49 percent. A completed sake can take any one of a million paths, depending on the methodology, forcefulness, order and especially the timing of these “post-brewing” processes.

brewing process before it. One brewer told me that he considers the last few steps, or “after-care” as he called it, to be about 51 percent of the quality of a sake, and the complicated pre-pressing steps only 49 percent. A completed sake can take any one of a million paths, depending on the methodology, forcefulness, order and especially the timing of these “post-brewing” processes.

Perhaps the easiest thing to look at as an example would be pasteurization. When a sake is pasteurized by essentially warming it up for a short spell, various things happen, most notably bacteria are killed, and enzymes are deactivated. This provides great stability to the product. But the timing of this step ( usually done twice, by the way) is a huge factor in how a sake matures.

Consider a freshly pressed tank of sake. It has residual enzymes, a bit of sugar and starch and a few stray yeast cells still hanging around and looking for some action. Like all late-night partiers, these folks will interact a bit and their presence will be felt. But once the police-sweep of pasteurization clears out the ‘hood, these colorful characters are gone, as is the potential effect of them having been there.

Waxing technical again, sake matures much more quickly when it is stored unpasteurized, and much more slowly after it has been pasteurized. So the longer a brewer waits to put the heat on, the fuller, richer, meatier, more pronounced-in-flavor the sake has a tendency to be.

Of course, nothing is quite that simple. It will mature after pasteurization, just not as vividly.

The point being, there are no hard and fast rules for the brewers to follow. What kind of sake is the brewer aiming for? How close or far from that is this particular batch? How slowly or quickly will that puppy in particular mature? When can it be expected to be shipped? How much time is there to play with, both before and after pasteurization? Can it be stored cold or must it be at room temperature, and what are the effects of that environment on what it is and what it will be? It is as frustratingly difficult as any other step in the brewing process, and exerts as much leverage as well.

The point being, there are no hard and fast rules for the brewers to follow. What kind of sake is the brewer aiming for? How close or far from that is this particular batch? How slowly or quickly will that puppy in particular mature? When can it be expected to be shipped? How much time is there to play with, both before and after pasteurization? Can it be stored cold or must it be at room temperature, and what are the effects of that environment on what it is and what it will be? It is as frustratingly difficult as any other step in the brewing process, and exerts as much leverage as well.

Traditionally, sake was pasteurized once very soon after brewing, then stored in a storage tank, and pasteurized again on its way to the bottle to ward off the effects of any bacteria it may have encountered on the way from said tank to said bottle. Today, however, there are countless variations of this once-standard way of processing.

Another not-so-simple issue is bottling. From long ago, sake was matured for six months or so in large tanks, then bottled later. But lately there has been a significant movement amongst craft brewers toward storing in bottles, not tanks, which calls for a much larger amount of warehouse storage space.

Huge. Still, many brewers find this yields a more fine-grained sake. Sake handled this way if often pasteurized just once, and more mildly as well.

The duration of maturation and dilution with water are similar in the myriad of affects that will result from different choices. Put them all together, and you can begin to see that the permutations are endless. Also, keep in mind there is no right way to do anything. It is all a function, obviously, of what style of sake the brewer intends to make.

Fine-grained, or big-boned? Light and dancing or settled and earthy? A one-glass sake or a session sake? All have their place and fans, and all call for different after-care.

At a tasting a while back of Shizuoka Prefecture sake, I made my way to the Kikuyoi booth. Shizuoka sits about an hour south of Tokyo,  and is the home of half of Mt. Fuji, as well as Japan’s best green tea and best wasabi. It has been a haven of good sake since the late 80s, rather than for centuries, but it is making up for lost time with a mighty vengeance.

and is the home of half of Mt. Fuji, as well as Japan’s best green tea and best wasabi. It has been a haven of good sake since the late 80s, rather than for centuries, but it is making up for lost time with a mighty vengeance.

Kikuyoi is brewed by owner-to-be and toji Takashi Aoshima. For now, let us just say there are great stories behind this brilliant guy, having looked askance at his sake-fate initially, then later returning to it with an unrivaled passion. His sake is settled and simple, delicately rich, and decidedly not ostentatious. I make a point of tasting it a lot – yea, verily, drinking it a lot – and as I worked across his table I noticed that the degree of maturity this time was exquisitely precise – more so than I recalled. The flavors stood out from their mellow background just perfectly.

Catching Aoshima-san for a brief moment after my run-through, I told him as much. “Your sake seems to be matured almost perfectly,” I offered.

“So! That’s right!” he blurted enthusiastically. “I agree wholeheartedly. I finally got the knack of it; it’s all in the timing of the pasteurization,” he explained.

“So now,” he continued, “I have, like, zero time. I am basically brewing in the winter, growing rice in the summer, and fiddlin’ with pasteurizing my sake and stuff like that in the gaps between.” The fact that he was beaming happily about his fate made it hard to feel sorry for him. He is famous for the dedication and energy he puts into brewing his sake, and it was evident in our conversation.

When next you come across an explanation on a label for from brewer on something as innocuous-sounding as pasteurization, bottle storage, or charcoal filtration remember that, as simple as those steps sound in comparison to koji and yeast starters and multiple additions, they carry quite the clout when it comes to the nature of the final sake.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Interested in learning more about sake, and the industry in Japan that makes it? Subscribe to Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Learn more and read a few sample issues here.

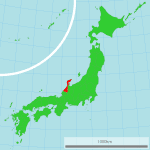

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today.

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today. eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate.

eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate. Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.