The acidity – or rather, the acid content, of a sake is from commonly listed on sake labels in Japan. While this is less common overseas, and that might not change (no great loss, really), it is still worth knowing just what it is and what it reflects. But it is not exactly an intuitive indicator.

The acidity – or rather, the acid content, of a sake is from commonly listed on sake labels in Japan. While this is less common overseas, and that might not change (no great loss, really), it is still worth knowing just what it is and what it reflects. But it is not exactly an intuitive indicator.

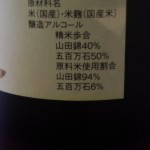

The numbers that express the san-do (acidity) are generally between about 1.0 and 2.0 or so. That is not a wide range, and most often the number seems to be about 1.1 or 1.2. The question is, 1.1 or 1.2 what?

Years ago, I began a quest to understand this. In turned out to be a monumental effort. I searched high and low, and asked almost everyone I could (outside of sake brewers themselves). Responses to this question placed to those that “should” know gave rise to whole plethora of silly answers. “Well, ..er, they’re units! Yeah, units.” Percent, tenths of a percent, and parts per million were some other replies, all expressed with sincerity and confidence.

It was truly hard to find anyone that knew in the world outside of sake breweries. Not that it is going to make that much of a difference in the enjoyment of sake, but you think people would be curious. Finally, I went straight to the source, and found out from a brewer.

Momentarily digressing beyond the normal scope of this newsletter and delving into a mercifully short chemistry lesson, here’s the explanation.

The number expressing the san-do of a nihonshu is the number of milliliters of liquid sodium hydroxide needed to neutralize ten milliliters of sake. It is, in other words, measured by titration, just as it is in wine.

So, what does all that mean to the average taster? Basically the acidity (and to a degree, the amino acid content) can give you at least a vague idea of what a sake might taste like just from looking at the label.

In particular, the acidity and the nihonshu-do are very often used together to give a pre-purchase indication of what the flavor profile might be like. A good high acidity may increase the sense of dryness of a sake by lightening and spreading out the flavor. A low acid content, on the other hand, can help a sake to feel fuller and heavier, and increase a sense of sweetness.

There are so many things that affect the fragrance and taste of a sake that to allow the description to depend on two parameters is limiting at best. But you have to try.

Modern Methods of Measurement

To a slight degree, the various grades of sake can be vaguely generalized by typical acid  content. For example, ginjo-shu often has slightly lower acidity, being light and fruitier. Junmaishu usually has acidity levels slightly higher on the scale. Sake made with the kimoto or yamahai method of preparing the moto will have even higher amounts of acid present, and can be quite puckering. But as in all things sake, there is great overlap here.

content. For example, ginjo-shu often has slightly lower acidity, being light and fruitier. Junmaishu usually has acidity levels slightly higher on the scale. Sake made with the kimoto or yamahai method of preparing the moto will have even higher amounts of acid present, and can be quite puckering. But as in all things sake, there is great overlap here.

But all this techno-babble is really only moderately useful, and only before you’ve tasted a sake. Once you’ve tasted it, you know all you need to know about acidity, sweet and dry, fullness of body and anything else.

Also, the method of measuring acid in sake is very similar to the methods for measuring acidity in wine: titration. And if one wanted to, one can express the total (almost) acidity of sake in terms of, for example, tartaric acid by multiplying the acidity number by 0.075. For comparison, sake has the equivalent of about 0.1 to 0.2 gms/100ml, comparted to an average of 0.5 to 0.9 gms/100ml in white wine.

The level of acidity will not always match presence of acidic flavor (known as the san-mi) in

the sake, due to alcohol, water quality, type of rice and other factors. Some sake will taste sharp and cutting, when in fact the acidity is not that high chemically. The opposite can also be true.

In the end it’s just a number, more useful to brewers than to consumers. At the same time, paying attention to acidity, amino acid content and nihonshu-do can be fun. Doing so can give rise to lively discussion, and help us pay more attention to our perceptions

From Monday, January 21, until Friday January 25, 2013, I will hold the 10th Japan-based Sake Professional Course in Tokyo, with a side trip to the Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe region. This is it: the most important thing I do all year, and beyond any doubt the best opportunity on the planet to learn about sake.

From Monday, January 21, until Friday January 25, 2013, I will hold the 10th Japan-based Sake Professional Course in Tokyo, with a side trip to the Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe region. This is it: the most important thing I do all year, and beyond any doubt the best opportunity on the planet to learn about sake. e” No Sake Stone Remains Left Unturned” is the motto, and “exceed expectations in that” is my goal. If you want to learn all you need to know about sake to function consummately as a sake professional at work, or if you are simply a sake lover with an insatiable appetite for sake-related knowledge, then this is the course for you. The course is recognized by the Sake Education Council, and those that complete it will be qualified to take the exam for Certified Sake Specialist, which will be offered on the evening of the last day of the course. Go

e” No Sake Stone Remains Left Unturned” is the motto, and “exceed expectations in that” is my goal. If you want to learn all you need to know about sake to function consummately as a sake professional at work, or if you are simply a sake lover with an insatiable appetite for sake-related knowledge, then this is the course for you. The course is recognized by the Sake Education Council, and those that complete it will be qualified to take the exam for Certified Sake Specialist, which will be offered on the evening of the last day of the course. Go