Here we are in the depths of winter. Although the days have begun to grow minutely if incrementally longer again, they continue to grow colder as all around us remains in hibernation. But this is just the time when the sake-brewing season is traditionally at its peak.

Here we are in the depths of winter. Although the days have begun to grow minutely if incrementally longer again, they continue to grow colder as all around us remains in hibernation. But this is just the time when the sake-brewing season is traditionally at its peak.

With actual brewing of initial batches having begun in November, most (if not all) breweries have pressed their first several batches of the season. Naturally this does not apply to large brewers that brew year-round, and there are also many that start earlier or even later than the average. But traditionally and statistically, the first few weeks of November see the pressing of the first tank of the year at many breweries. Being January now, most breweries are in the thickest part of the season, finishing batches and starting new ones on daily or almost-daily basis.

And along with this first pressing comes a handful of terms – with greatly overlapping meanings – to describe the resulting sake.

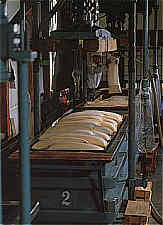

After the tank of rice, water, koji and yeast has run the course of fermentation, the clear sake must be  separated from the white slurry of rice solids that remain. This step is usually done by a machine that forces the slurry though fine mesh panels, catching the solids and letting the amber ambrosia pass through. There are of course other, more labor intensive, quality-imparting methods then these machines.

separated from the white slurry of rice solids that remain. This step is usually done by a machine that forces the slurry though fine mesh panels, catching the solids and letting the amber ambrosia pass through. There are of course other, more labor intensive, quality-imparting methods then these machines.

Regardless of the method, this pressing step is known as “ shibori.” and the first pressing of the brewing season is “ hatsu-shibori.” We can often find sake labeled “ shibori-tate,” meaning “just pressed” on shelves of sake retail shops.

Another term greeting us from sake labels early in the new year is “ shinshu,” or “new sake,” which is sake that is, well, new. Most sake is aged after pressing for from about six months to about 18 months, although there is great variation in this as well from brewery to brewery. Aging sake like this allows the just-pressed new-sake brashness to mellow and round out, not unlike what happens with wine. Shinshu is sake released without this maturation, and as such has a fresh and brash youthfulness to the flavor.

So, one might ask, what is the difference between the two terms used above, shibori-tate and shinshu? The main inference is that a shibori-tate is just out of the presses, with all of the attendant brashness that implies, whereas a shinshu may have been pasteurized, filtered, and tweaked, but simply has not been aged for long, if at all. And yes, there is a whole lot of overlap there.

Much sake released now is also nama-zake, which is sake that has not been pasteurized. Pasteurization in sake means temporarily heating it gently to deactivate enzymes that could alter the flavor. These active enzymes could send the sake awry and out of balance if it is not kept cold. Sake that has not been pasteurized (i.e. nama-zake) has a zingy, fresh, appealing lilt to the fragrance and flavor, although this aspect can overpower the true nature of the sake if it is not kept in check during production.

Much sake released now is also nama-zake, which is sake that has not been pasteurized. Pasteurization in sake means temporarily heating it gently to deactivate enzymes that could alter the flavor. These active enzymes could send the sake awry and out of balance if it is not kept cold. Sake that has not been pasteurized (i.e. nama-zake) has a zingy, fresh, appealing lilt to the fragrance and flavor, although this aspect can overpower the true nature of the sake if it is not kept in check during production.

Much shibori-tate is nama-zake as well, as is much shinshu.

Not enough terminology for ya? Thirsty for more? Here are a few more that, while by no means limited to this time of the year, may be a bit more common to this season.

Genshu is sake that has not been cut with water after brewing. Sake ferments naturally to about 20 percent alcohol, which is a bit high to allow the fine nuances to come through. It is therefore usually cut with water to bring it down to about 16 percent alcohol. Genshu has not had water added, and therefore is a bit stronger. This often complements the rough-and-tumble brashness of shibori-tate sake.

“Muroka” unfiltered, in the sense that it has not been charcoal filtered. Most sake, after pressing, is at  some point in time filtered using powdered active charcoal to fine-tune the flavor and remove unwanted aspects. (This filtering process is curious to watch, as they actually dump a bunch of fine, black powder into this lovely sake, then filter it out.) Muroka sake has a wider range of flavor components, and again refraining from filtering augments the appeal of freshly-pressed sake. It all works together.

some point in time filtered using powdered active charcoal to fine-tune the flavor and remove unwanted aspects. (This filtering process is curious to watch, as they actually dump a bunch of fine, black powder into this lovely sake, then filter it out.) Muroka sake has a wider range of flavor components, and again refraining from filtering augments the appeal of freshly-pressed sake. It all works together.

Note that often several of these terms can be found one label. For example, you can have a shiboritate nama muroka genshu, and it would not be at all uncommon or strange, even if it is a mouthful (in more than one sense of the word).

But in the end, the terminology is ancillary in importance, and all that really matters is enjoying freshly-made sake when it is best: now.

~ ~ ~

Amidst all these terms is one more, self-explanatory (if you understand Japanese, that is) very rarely seen – Gantan Shibori. Gantan is the word for New Year’s Day. So a sake marketed as Gantan Shibori will have been pressed on January 1, and shipped out immediately so as to be enjoyed on that day or very soon thereafter.

While of course this tells us nothing about the grade of the sake, it will surely be nama, muroka, and most likely genshu. And it will of course be shibori-tate and shinshu too! So you kind of the whole kit-n-caboodle in a bottle of Gantan Shibori.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sake Professional Course in Chicago

April 23 ~ 25, 2019

From Tuesday, April 23 to Thursday, April 25, 2019, I will hold the 30th North American running of the Sake Professional Course at the restaurant Sunda, in Chicago, Illinois. The content of this intensive sake course will be identical to that of the Sake Professional Course held each January in Japan, with the exception of visiting sake breweries.

From Tuesday, April 23 to Thursday, April 25, 2019, I will hold the 30th North American running of the Sake Professional Course at the restaurant Sunda, in Chicago, Illinois. The content of this intensive sake course will be identical to that of the Sake Professional Course held each January in Japan, with the exception of visiting sake breweries.

The course is recognized by the Sake Education Council, and those that complete it will be qualified to take the exam for Certified Sake Specialist, which will be offered on the evening of the last day of the course.

You can learn more about the course here, see the daily syllabus here,and download a pdf here. If you are interested in being in the mailing list for direct course announcements, please send me an email to that purport.

Testimonials from past graduates can be perused here as well.