It’s complicated…

One of the more idiosyncratic aspects of the sake world is the distribution system via which brewers get their rice. It certainly is not simple, and at one time it probably made sense. Certainly there are many that benefit from it – both brewers and farmers – and others for whom it serves them less. And, of course, there are those that have the means and cleverness to work around it if need be. Let’s look at it a bit more closely.

One of the more idiosyncratic aspects of the sake world is the distribution system via which brewers get their rice. It certainly is not simple, and at one time it probably made sense. Certainly there are many that benefit from it – both brewers and farmers – and others for whom it serves them less. And, of course, there are those that have the means and cleverness to work around it if need be. Let’s look at it a bit more closely.

The place to begin is to realize that sake brewers do not grow their own rice. Fundamentally speaking, since just after World War II, companies, i.e. business entities are not permitted to grow rice. All rice is grown and sold by individual farmers. Business entities are basically not allowed to be involved. Things have changed a little bit recently and there are some exceptions, but basically sake brewers cannot own their own rice fields, or grow their own rice.

Why is this the case? It is to prevent the reconsolidation of farmland. Long ago, owners of huge tracts of land controlled things, rather than the peasants living on it and growing on it. For reasons beyond my comprehension (although my sense of common decency says it’s not cool) this is not a stable situation economically. Regardless of the reasoning, this keeps rice plots spread out and small, with the average being about 1.65 acres, compared to farms typically 160 times that in the US.

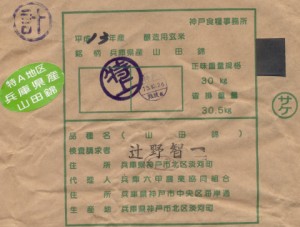

Rare shot of rice when flowering (Psst! It’s Yamada Nishiki!)

This lead to the creation of agricultural cooperatives, about which more could be written than the scope of this newsletter can hope to contain. But in short, local farmers have their rice distributed to the market through local agricultural co-ops, from whom they are often obligated to buy fertilizers, insecticides and more. But these co-ops then negotiate prices and secure livelihood for the local farmers and others. They are also necessarily competitive organizations, and do their best to promote the brands of rice that grow best in their region.

And for many brewers, this is the easiest way to go. They order a certain rice grown in a certain region, and almost always, they will get it. They cannot specify just who the grower is, just the variety, inspected grade, and region. And while sometimes shortages do occur, almost always they get what they ordered.

Then, a scant 15 years ago or so, laws changed that allowed brewers to bypass the co-ops and form contracts with farmers to buy rice directly. This is great for a number of reasons. They can “see the faces” of the producers, dictate a bit more about how it is grown if they want to, and see it at every step of its evolution. However, there are downsides as well to going with single producers via contract.

For example, what if there is a bad year, and harvested amounts are low? When one buys from an agricultural co-op that draws from many growers, it is easy to cover those shortages. Sure, somebody somewhere gets stiffed, but it’s a game of supply and demand, and who orders first.

But if they buy from one farmer drawing from just a few fields, a bad year means less rice, which must then be bought later, elsewhere, and may be neither the quality level or price that was initially sought.

But if they buy from one farmer drawing from just a few fields, a bad year means less rice, which must then be bought later, elsewhere, and may be neither the quality level or price that was initially sought.

And what if there is a bumper crop? While that sounds great, it might not be. Again, buying from a co-op is no problem. “You ordered this much, you get this much. The surplus is our problem.” But if you buy it via contract on a field, if they have bumper crop, you are stuck with paying for and then dealing with all that excess rice that grew on that field. After all, the grower reserved it all for you. And while you might be tempted to think, “Well, just make more sake with it!” it is not that simple practically, economically or even legally.

Of course, there are ways to work around both of the above issues; the point here is simply to show the pros and cons of each, and how big an issue procuring rice is for sake brewers.

Only about 1.4% of all rice grown in Japan is sake rice. Obviously, it is not a cash crop, nor the priority for most farmers, or the co-ops. Wide plains are reserved for more lucrative-to-grow table rice, and often sake rice gets relegated to the harder-to-till parcels. Not always, mind you; but often.

Also, a few years back, it became legal for brewers themselves (actually, some business entities) to grow rice. One would think, “Hey, now this changes everything, duddn’t it!” But in reality, very few have begun to do that. A few have, and surely others welcome the idea in concept. But gearing up to farm when you do not have the people, experience and tools is major hassle, and on top of that, the relationships with those that can do it well are in place. Let it ride.

But in truth there are many patterns. One brewer I know well maintains about 25 fields around his region, small parcels of land that are owned by folks too old to work them anymore. My brewer friend rents them for very little, and it is win-win as he gets to grow his rice his way, and he keeps the land arable too, which the owners like.

“It has its attendant issues,” he lamented hesitatingly. “Often, those old folks can be a pain in the ass.”

Why then, I suggested, do you not just buy the land from them? The terseness of the wave of his hand with which he dismissed that suggestion clearly conveyed its ridiculousness.

“Land prices are high; profit margins on rice and sake are miniscule. It would take me well over a full century to reap a return on my investment!”

So while many brewers might the romantic notion of growing their own sake rice, it is often not a practical option.

As rice distribution really is a murky and vague topic, let us look at it again in next month’s newsletter, when we will see how government allocations of land, and the subsidies related to that, can significantly affect rice supplies. That, and more murky rules. For now, suffice it to say that procuring rice for sake in Japan is significantly different from procuring grapes for wine, anywhere.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sake Professional Course Sake Pro Course NYC 2013

Kikizake-joko – Official Tasting Glasses

Dallas, Texas, August 8~10, 2013

The next Sake Professional Course will take place August 8-10, in conjunction with TEXSOM 2013 at the Four Seasons Resort and Club Dallas at Las Colinas in Irving, Texas

More about the seminar, its content and day-to-day schedule, can be found here.

The Sake Professional Course, with Sake Education Council-recognized Certified Sake Professional certification testing, is by far the most intensive, immersing, comprehensive sake educational program in existence. The three-day seminar leaves “no sake stone unturned.”

The tuition for the course is $825. Feel free to contact me directly at sakeguy@gol.com with any questions about the course, or to make a reservation.

Several municipalities and one prefecture have recently put into effect actual legal ordinances dictating that if you say “kamapai!” it must be with sake (or in one case, shochu, Japan’s indigenous distilled beverage).

Several municipalities and one prefecture have recently put into effect actual legal ordinances dictating that if you say “kamapai!” it must be with sake (or in one case, shochu, Japan’s indigenous distilled beverage).

![image824190[1]](http://sake-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/image8241901-100x150.gif)