Next year will mark the 60th anniversary of the discovery of perhaps the most important sake-brewing yeast strain of all, the Kumamoto yeast, also known as Yeast Number Nine.

Next year will mark the 60th anniversary of the discovery of perhaps the most important sake-brewing yeast strain of all, the Kumamoto yeast, also known as Yeast Number Nine.

While the yeast itself, its qualities, and its various aliases are worth knowing about, the history and culture surrounding all this is interesting as well. It all took place down south in Kumamoto Prefecture, thanks to the efforts of a man named Professor Kin’ichi Nojiro.

Back in the Edo period, when samurai clans still ruled the various provinces, before the Meiji Restoration in 1868 when power was returned to the Emperor and modern government was installed, there was no sake as we know it in Kumamoto. Instead, the ruling clan had dictated that a red type of sake, known as “akazake,” was the only type of sake to be brewed. It was likely an economical decision, an effort to make Kumamoto the capital of this curious brew. (The color comes from an ash put in the sake to preserve it. It is still available today; it all comes from Kumamoto and is used only in cooking.)

While that worked for a while, it put Kumamoto a bit behind the rest of the country in real sake brewing technology. In order to address this, Kumamoto Prefecture put a lot of research effort into brewing good sake, forming a company that functioned as a brewery and research center. It is still around today, and the wonderful sake brewed there is called Koro. One of the main forces in the research center devoted to that effort was Professor Nojiro.

Among other advances in brewing techniques, he discovered a yeast strain in 1953 that soon propelled Kumamoto sake to the top of the sake-brewing world. Initially, it was known as the Kumamoto Kobo (yeast). Soon, a very similar yeast was isolated, and thereafter the two came to be known as KA-1 and KA-4.

Eventually, an organization called the Nihon Jozo Kyoukai, or Brewing Society of Japan, began to propagate and sell this yeast to brewers around the country. Henceforth, when supplied by this organization, it came to be known as Association Yeast Number Nine.

So, to clarify, for those that are interested, if the label says Yeast #9, it came from The Brewing Society of Japan, who got it a few months before that from the company that makes Koro in Kumamoto. If it says KA-1 or KA-4, you know that brewer has a connection and was able to snag some directly from Koro, without going through any other organization.

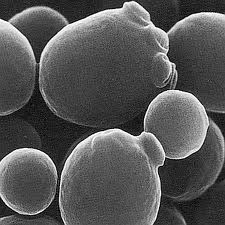

It is very difficult to keep yeast strains like this pure over the generations and generations of reproduction required to use them in large quantities year after year. Those doing that work must test carefully to be sure that the qualities of the yeast do not change. The folks at the Kumamoto research center work hard to create consistent KA-1 and KA-4 each year, and the Japan Brewers’ Association gets fresh stuff from Kumamoto each year, ensuring their strains are pure as well.

This family of yeast is very suited to making aromatic yet clean ginjo-shu. And today, more of that kind of fine sake is being produced then ever before. This leads to great demand for the #9 strains. So what some prefectures do (most notably Yamagata, but other places as well) to make it more accessible is to buy some Kumamoto Kobo from the source, then propagate it at home, and distribute it amongst those that want it in that prefecture. This is significant only because amongst Yamagata sake, one can find a yeast called Yamagata KA, which is Yamagata home-grown Kumamoto Kobo.

So at the end of the day, KA-1 and KA-4, Kumamoto Kobo, #9, and Yamagata KA are more or less the same yeast. Consider it “family number nine” or maybe “Kumamoto lineage.” Naturally, there are those who insist the original pure strains from Kumamoto are better. But what is important to remember is that this line of yeasts is the most widely used yeast in ginjo sake brewing, and has stood the test of 50 years’ time without being dethroned, and without significantly mutating.

So what is so special about it? In brewing, it ferments thoroughly and slowly at low temperatures, allowing brewers to control the fermentation closely. This all leads to wonderfully smooth and fine-grained flavors, good aromatic acid content, and lovely fruity aromas reminiscent of delicious apples and perhaps melon. Clean and bright sake with wonderful balance is the trademark of this line of yeasts. Indeed, there is nothing quite like classic #9 flavors and aromas in a sake.

Indeed, these days especially, there are many other great yeasts. Whether or not they will still be great in 50 years is yet to be seen. And it is certainly possible to enjoy your sake without giving a hoot about the yeast used. But often, the more one tastes, the more one wants to know why certain sake have the aromas and flavors they do, to know what makes a sake the way it is. Should your interest get to that level, remember ole’ Number Nine.

The company that makes Koro is still alive and well, and ownership of it is shared amongst all the other brewers in Kumamoto. The president-ship rotates amongst the presidents of the other Kumamoto brewery owners.

Koro is truly a lovely sake in all of its manifestations. Then name itself means “fragrant

dew.” I like to refer to it as the Pilsener Urquell of sake. It really is the quintessential manifestation of ole Number Nine. Melon, a light spritzy acidity, and incredible balance from beginning to end. Just ever so slightly restrained and understated, it is a tad different from the aromas of much modern ginjo sake. It is very limited in its availability in the US. And that is just the junmai ginjo. They make a daiginjo as well that is hard to get anywhere.