Also known as “Awanashi Kobo”

Admittedly, the subject of yeast types begins to push the envelope of geekdom, ever-so-slightly encroaching into the realm where most folks’ interest in sake begins to wane. While some want to know both in theory and practice the difference between a Number 9 and a Number 10, and perhaps even between a CEL-24 and EK-1, most of us are content to sip and smile. Even so, there are some interesting historical, cultural and technical anecdotes surrounding even things as dryly scientific as yeast, making it well worth a look-see for those that like sake. The lore – dare I say subculture? – surrounding foamless yeasts, or “awanashi kobo,” is one such example.

Admittedly, the subject of yeast types begins to push the envelope of geekdom, ever-so-slightly encroaching into the realm where most folks’ interest in sake begins to wane. While some want to know both in theory and practice the difference between a Number 9 and a Number 10, and perhaps even between a CEL-24 and EK-1, most of us are content to sip and smile. Even so, there are some interesting historical, cultural and technical anecdotes surrounding even things as dryly scientific as yeast, making it well worth a look-see for those that like sake. The lore – dare I say subculture? – surrounding foamless yeasts, or “awanashi kobo,” is one such example.

First of all, just what is foamless yeast? Usually, when sake undergoes its 20- to 40-day fermentation, the foam rises in great swaths and falls again, especially over the first third or so of this period. Last month, we talked about the appearance of the foam, and how much brewers can deduce from watching it. You can read that here.

The sake brewers of olde would judge the stage, progress and condition of a given batch by the appearance (and smell, and taste, and even sound) of this foam topping. Many brewers simply prefer the foam, as it gives them one more source of all-important input that can be used in assessing the progress of a fermenting tank, and when a sake is ready to be pressed. The five senses are, after all, the most reliable tools of the sake-brewing craft.

Also, there are ten times more yeast cells in the foam than the mash itself, so very often yeast for subsequent batches is removed from the foam of healthy, vibrantly fermenting tanks.

So foamless yeasts, obviously, are strains of yeast that do yield bubbles and foam on the top of the moromi (fermenting mash) as they ferment away and convert sugars to alcohol, carbon dioxide, and more. (Actually, even foamless yeasts create a little bit of foam.) The question is, if brewers can learn so much from the appearance of this foam, then why would anyone want to use these foamless yeasts? There are, actually, a number of very good reasons. Most of these are centered around efficiency, sanitation, labor-savings, and even safety.

For instance, since the foam rises so high during fermentation, brewers cannot fill a tank to the brim with rice, koji and water since it  would soon overflow with foam, leading to hygienic nightmare. Rather, they can only fill the tank initially about 3/4 of the way to leave room for the foam to rise and fall. Naturally, this puts a damper on one’s yields and efficiency. With foamless yeasts, however, this concern is all but a non-issue, and a brewery can get much higher yields out of each batch and tank, which contributes massively to the overall efficiency of a year’s worth of brewing.

would soon overflow with foam, leading to hygienic nightmare. Rather, they can only fill the tank initially about 3/4 of the way to leave room for the foam to rise and fall. Naturally, this puts a damper on one’s yields and efficiency. With foamless yeasts, however, this concern is all but a non-issue, and a brewery can get much higher yields out of each batch and tank, which contributes massively to the overall efficiency of a year’s worth of brewing.

Also, when foam does rise and fall, the remains that cling to the side of the tank are a veritable hotbed of bacterial activity, an orgy of undesirable microorganisms just hankerin’ to drop back in and do damage to the unsuspecting ambrosia-in-waiting below. So this must be assiduously cleaned off by the brewers. Not only is this hard and time-consuming work, it is also quite dangerous, since it generally requires leaning into the tank.

So by eliminating the foamy remains, time, labor, and risk are spared. Finally, without all that gunk in the way, the hard-working yeast cells move and work a bit more freely, so that fermentation proceeds a smidgeon faster and can finish a day or two earlier.

Why are they foamless? What happens, it seems, is that most yeast cells will cling to bubbles of carbon dioxide that are created and then rise to the surface. Foamless yeast cells, on the other hand, for whatever reason do not cling to these bubbles and so are not carried up, up, and away. Since the bubbles are unencumbered, they pop, and there is no foam rising high above the mash.

The foamless yeasts that are commonly encountered out there today are non-foaming versions of the “usual suspects,” rather than being new, unknown, or total mutant life-forms. Most of the foamless yeasts commonly seen used in sake these days are simply foamless versions of the main Brewing Society of Japan yeasts, i.e. Numbers 6, 7, 9, 10, 16 and lately 18 (which, actually, does not even have a foaming counterpart!). There are others, of course, but we just hear about them less often.

The foamless yeasts that are commonly encountered out there today are non-foaming versions of the “usual suspects,” rather than being new, unknown, or total mutant life-forms. Most of the foamless yeasts commonly seen used in sake these days are simply foamless versions of the main Brewing Society of Japan yeasts, i.e. Numbers 6, 7, 9, 10, 16 and lately 18 (which, actually, does not even have a foaming counterpart!). There are others, of course, but we just hear about them less often.

Actually, these too are naturally occurring. About one in every several hundred million yeast cells of a given type are foamless, but obviously, if just one in several hundred million is non-foaming, no one will notice. It just takes patience to isolate some and cultivate a pure culture of them.

Also, they have been around a long time, it seems, but proper records go back until only about 1916, when several breweries reported experiences with them. Apparently, until then, the brewers that encountered these thought, “ Whoa. This can’t be right. Let’s just quietly throw this mutant away before anyone finds out about it. It could be bad for our rep and all.”

But then in 1931, the Sake Research Center in Niigata successfully brewed a proper batch with foamless yeast. In 1963, based on some foamless yeast isolated at a brewery in Shimane making a sake called Hikami Masamune, researchers began to study it properly, and with the help of a local-to-Shimane famous sake professor named Yuichi Akiyama (that was until recently still active and famous), in 1971 the foamless version of Number 7 became available to brewers around the country.

However, the first commercial use of a foamless yeast was actually in Hawaii, believe it or not. That was in 1960 or 1961, a full ten years before it was used on anything remotely resembling a large scale in Japan, by Mr. Takao Nihei of the Honolulu Sake Brewery. Dispatched by the brewing research organization within the government of Japan, he was the first to take what information there was on these yeasts (and a sample, of course) and run with it. His focus was saving labor and producing great sake with great efficiency, and this he did with great success.

Are these foamless yeasts really the same as their bubbling counterparts, except for the foam? I mean, c’mon; really? I always take the  opportunity to ask that question whenever I visit a brewery using foamless yeast, being sure to pretend it is the first time I have ever done so. Most of the time they would answer, “Yes, the results are essentially same, and the practical advantages make it a clear choice for us.” However, there are a still a few hardcore brewers who insist that the foamless manifestations are not quite as good as the foaming yeasts. Naturally, the ability to gather information from the appearance of the foam is eliminated. Still, most brewers feel that with foamless yeasts they get the same quality of sake, with less mess.

opportunity to ask that question whenever I visit a brewery using foamless yeast, being sure to pretend it is the first time I have ever done so. Most of the time they would answer, “Yes, the results are essentially same, and the practical advantages make it a clear choice for us.” However, there are a still a few hardcore brewers who insist that the foamless manifestations are not quite as good as the foaming yeasts. Naturally, the ability to gather information from the appearance of the foam is eliminated. Still, most brewers feel that with foamless yeasts they get the same quality of sake, with less mess.

A final technical note for those that are interested: foamless yeasts, at least those distributed by the Brewing Society of Japan, are designated by a -01 after the normal nomenclature. So a foamless Number 7 is known as 701, foamless Number 9 as 901, and so on. Those you are likely to come across are 601, 701, 901, 10-01, 1601 and 1801 (for which there is no regular #18).

Take the time to look for the yeast used in your sake. Sure, it’s a bit maniacal, but fun as well. And if you see one of the numbers ending in -01 above, you know just what it is.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Interested in learning more about sake, and the industry in Japan that makes it? Subscribe to Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Learn more and read a few sample issues here.

Again, this really does not happen anymore; nor was it ever a huge industry problem. But I have heard about it from several brewers, elevating it above simple legend. Also, just getting a good yeast is not the end of the challenge. A brewer with any new yeast needs to learn its idiosyncrasies during preparation, throughout fermentation, and beyond.

Again, this really does not happen anymore; nor was it ever a huge industry problem. But I have heard about it from several brewers, elevating it above simple legend. Also, just getting a good yeast is not the end of the challenge. A brewer with any new yeast needs to learn its idiosyncrasies during preparation, throughout fermentation, and beyond.

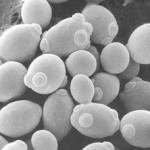

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake. In terms of how these are reproduced, it varies a bit from yeast to yeast. But basically, stock yeast cells are put into an environment that encourages reproduction. Kind of like a love hotel for yeast, I guess. The resulting yeast cells are harvested, and washed with sterilized water, analyzed for purity and quality, and then bottled in little glass ampules.

In terms of how these are reproduced, it varies a bit from yeast to yeast. But basically, stock yeast cells are put into an environment that encourages reproduction. Kind of like a love hotel for yeast, I guess. The resulting yeast cells are harvested, and washed with sterilized water, analyzed for purity and quality, and then bottled in little glass ampules.

Back about 80 years ago when this organization was put together, they started to reproduce yeast that was known to be strong and predictable, and make it available to any brewer in the industry in little ampules. This helped ensure good sake, which led to good tax revenue. 😉

Back about 80 years ago when this organization was put together, they started to reproduce yeast that was known to be strong and predictable, and make it available to any brewer in the industry in little ampules. This helped ensure good sake, which led to good tax revenue. 😉 predecessors, it now may be giving Number 7 a run for the money in how commonly it is used.

predecessors, it now may be giving Number 7 a run for the money in how commonly it is used.