An important period in the history of sake

When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed.

When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed.

While admittedly conversations about how to know just what it is you are drinking, or how to discover your preferences, are more relevant today than the stories of the days of olde, sake’s foray into and back out of the religious ranks is an interesting one.

To follow and understand it all, however, one first needs a perfunctory knowledge of Japan’s history. Until the 8th Century or so Japan was ruled fairly well by an extended imperial court, replete with the emperor and other royals. During this time, most sake was brewed by this court (they had their own brewery on the premises of the palace in Nara) for their own consumption, although much of this was also made for festivals and ceremonies rather than frivolity.

But slowly, aristocratic warrior classes took over the de-facto ruling of the country, although the imperial court continued to rule in name only. Seeing the inherent opportunity, the military government allowed production to extend into the private sector, with sake taxes first being applied in A.D. 878. They continue today.

But sake also – not surprisingly – has religious applications as well, at least in the indigenous religion of Japan, Shinto. (Shinto is  characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods.

characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods.

So, even the military ruling elite gave the gods a tax break, and tax-free sake began to proliferate in Shinto shrines, ostensibly for religious purposes only. But Buddhism was also gaining ground in Japan, and as a result of some unique blend of vagueness and tolerance, very often Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples lovingly shared the same grounds. While the two religions have very different tenets, they coexisted very peacefully. “Hey, it’s all good, man” is what the clergy of old likely muttered about. This continued until the Meiji era, when Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples were forcibly separated by decree of the new Meiji government.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Know more. Appreciate more.

Announcing the launch of a new sake publication, Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Free until December 1! Subscibe before then and enjoy an 80% discount for ever. Learn more here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And so, while alcohol is not a part of Buddhist worship, since they shared ground, they shared sake, and they shared the brewing workload. And while, officially, no partaking of the libation was permitted outside of the religious ceremonies, no doubt they were nipping at the product here and there. In fact, they even had a nickname for it to obfuscate the truth from outsiders. Sake drunk by the clergy in temples was known as “Hanyatou,” which (very) loosely translates into “the warm water of wisdom and truth.” How true; how true.

So, for a few hundred years – beginning in the 10th or 11th century and continuing to some degree into the 15th – much sake brewing was centered in temples and shrines. During this time, the monks of the temples in Nara would occasionally travel to China for Buddhist instruction, and a lot of the brewing technology of that time originated from what those monks picked up while in China, and later modified to suit local tastes and objectives.

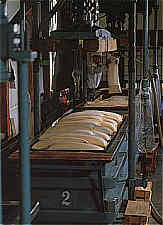

And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice.

And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice.

But in 1420, the military rulers made it officially illegal for Buddhist monks to drink, or for sake to be brought into Shinto shrines. While it is unclear how this was enforced, sake brewing began to move more actively into the then-equivalent of the private sector.

Still, these medieval entrepreneurs took the clerically developed technical advances and ran with them, slowly but surely improving both quality and economies of scale. Soon enough, places like Itami and then Nada (both in nearby Hyogo prefecture) rose as very prominent regions of sake production. But they had to attribute much of their success to the monks and priests of the temples and shrines.

Today, there are about ten Shinto shrines that still make a form of sake for religious purposes. But it is hardly the kind of sake we consumers normally enjoy. It is more like a wildly fizzy rice-dosed very thick nigori-zake (cloudy sake). Kind of like nigori on steroids.

Although all of this is a far cry from most ohttps://sake-world.com/sin/f the ginjo and other premium sake we all enjoy today, in a sense we owe a debt and at least an acknowledging thought of gratitude to the Buddhist and Shinto priests of old.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Know more. Appreciate more.

Announcing the launch of a new sake publication, Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Free until December 1! Subscibe before then and enjoy an 80% discount for ever. Learn more here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

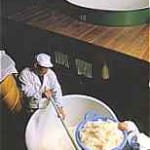

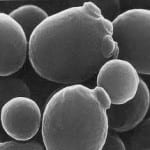

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake.

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake. One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.)

One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.) That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.

That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that. Fukushima Prefecture is currently the sake-brewing region garnering the most attention, at least as far as the industry is concerned. Consumers, of course, may not have the same figures of merit as those that brew and assess sake. There are of course many very famous Fukushima sake amongst consumers as well, but when it comes to technical prowess, most consumers could care less. But the industry pays attention to that stuff, and unquestionably, Fukushima rocks.

Fukushima Prefecture is currently the sake-brewing region garnering the most attention, at least as far as the industry is concerned. Consumers, of course, may not have the same figures of merit as those that brew and assess sake. There are of course many very famous Fukushima sake amongst consumers as well, but when it comes to technical prowess, most consumers could care less. But the industry pays attention to that stuff, and unquestionably, Fukushima rocks. beverages as well, at least to some degree. But they are large part of modern sake aromatic and flavor profiles. And in short, isoamyl acetate smells a lot like banana, and ethyl caproate smells a lot like apple, although it can also come across as strawberry, tropical fruit or even anise.

beverages as well, at least to some degree. But they are large part of modern sake aromatic and flavor profiles. And in short, isoamyl acetate smells a lot like banana, and ethyl caproate smells a lot like apple, although it can also come across as strawberry, tropical fruit or even anise. However, in blind tastings on the ginjo and daiginjo level, results tend to favor the above-described formula. And, really, the main point here is that these things can be scientifically categorized, and this gives sake brewers a “strike zone” for which to aim, if brewing such sake is their goal.

However, in blind tastings on the ginjo and daiginjo level, results tend to favor the above-described formula. And, really, the main point here is that these things can be scientifically categorized, and this gives sake brewers a “strike zone” for which to aim, if brewing such sake is their goal.