This article originally appeared in the April 15 issue of Sake Industry News.

Amongst the many steps of the sake brewing process, some are more glamorous than others, and that therefore garner more attention. “Koji-making” and “yeast starter” sound so much more romantic than “milling the rice.” As such it becomes easy to dismissively abridge the more mundane-sounding processes, and even more so when modern machines do a much better job than hassle-laden traditional hand-crafted methods.

Amongst the many steps of the sake brewing process, some are more glamorous than others, and that therefore garner more attention. “Koji-making” and “yeast starter” sound so much more romantic than “milling the rice.” As such it becomes easy to dismissively abridge the more mundane-sounding processes, and even more so when modern machines do a much better job than hassle-laden traditional hand-crafted methods.

And rice milling is the epitome of this. We usually say, “first, they mill the rice…” and move on to the more glamorous steps. But that belies how incredibly important milling is. One could say it is the most important step, since if the rice is not milled well – if there are lots of cracked or broken grains as one example – then the rest of the processes will not proceed well and the resulting sake will suffer.

Why, again, do they mill the rice? The objective is to remove fat and protein from the outside of the rice grains while leaving the starch in the middle intact, and doing this in such a way that the rice grains do not crack or break. Protein and fat can give character to sake, but they are usually viewed as the cause of rougher flavors. And avoiding cracking and breaking while milling is important so as to let the microorganisms used in the process to do what they need to do effectively and predictably.

From eons ago, rice in Japan has been milled a bit before being consumed. But really, only the outer eight to ten percent is milled away; that is enough to significantly improve the way it tastes. Long ago rice was milled using using grinding stones, often driven by water wheels when available. But this was rough, and only the very outer portion (that eight to ten percent) could be milled away.

In 1896, the company Satake, located in Hiroshima, developed automatic milling machines that made all that much easier. And that  company grew into the largest rice milling machine company in the world, which they remain today. In the 1930s, Satake went on to develop special milling machines to mill rice especially for sake brewing. These employed harder milling stones that were much larger, and through these developments brewers were able to mill the rice much farther then ever before. This technology led to higher and higher milling rates, and eventually, the advent of ginjo-shu.

company grew into the largest rice milling machine company in the world, which they remain today. In the 1930s, Satake went on to develop special milling machines to mill rice especially for sake brewing. These employed harder milling stones that were much larger, and through these developments brewers were able to mill the rice much farther then ever before. This technology led to higher and higher milling rates, and eventually, the advent of ginjo-shu.

So for a long while, it was all about Satake. But note, the company’s bread and butter (or rice and pickles, as it were) was machines for table rice, a market they dominate today as well. But there are other milling machine producers, and many have come and gone. Today, the other main company that makes rice milling machines is Shin-Nakano. Both are great companies, and both continue to make their presence felt.

Shin-Nakano, while a much smaller producer of milling machines, is part of larger holding company that owns other sake industry businesses, including a couple of sake breweries as well. And they have maintained plenty of relevance by focusing on craft breweries, and offering plenty of added value, in the form of research with backed by proper scientific methods that has from time to time gone against what has been common sense in the industry. For this and other reasons, many sake brewers stick with Shin-Nakano machines, and they are quite visible in the sake world.

But beyond the machines themselves and their producers, there are developments that start out as ideas in the minds of brewers and such, and eventually work their way into the technology. One of those is what is called Henpei Seimai, or flat milling.

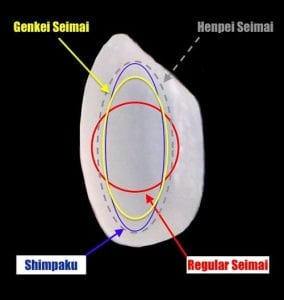

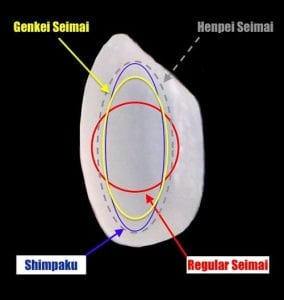

In order to grasp Henpei Seimai, remember that rice grains are not round, but are oblong, kind of like a rugby ball, and the starch center known as a shinpaku within is also basically of that shape. And like many of us human beings, there is much more meat around the midsection than at the top or bottom. This “meat” in sake rice is fat and protein. But when milling machines mill, they take the rugby-ball-shape and make it round by milling evenly everywhere around the grain. This means that, when milling is done, there is more fat and protein around the sides of the shinpaku then at the ends.

In order to grasp Henpei Seimai, remember that rice grains are not round, but are oblong, kind of like a rugby ball, and the starch center known as a shinpaku within is also basically of that shape. And like many of us human beings, there is much more meat around the midsection than at the top or bottom. This “meat” in sake rice is fat and protein. But when milling machines mill, they take the rugby-ball-shape and make it round by milling evenly everywhere around the grain. This means that, when milling is done, there is more fat and protein around the sides of the shinpaku then at the ends.

If they could somehow maintain the oblong shape and mill more around the midsection then at the top or bottom, a higher ratio of fat and protein could be removed. This idea was proposed about thirty years ago by Mr. Tomio Saito, a former Chief Official Appraiser at the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau.

And it worked! The concept was embraced by Daischichi brewery in Fukushima, and others followed soon after that, and Henpei Seimai was born. (Actually, Daishichi takes it a bit further and calls it Cho-henpei Seimai, or “Super Flat Milling.” You can learn more about that here.)

Henpei Seimai does not call for special milling machines. It just calls for modifying and jury-rigging older machines, a lot of skill and a  ton of patience on the part of the miller. But basically things are tweaked so that the rice grains fall in fewer numbers against the milling stone, and maintain a vertical orientation as they do. This means that more gets nicked off the sides each time than the top or bottom, and the henpei seimai goal is achieved. So anyone with the requisite skill and experience can do it, it just takes longer, and uses more energy as well.

ton of patience on the part of the miller. But basically things are tweaked so that the rice grains fall in fewer numbers against the milling stone, and maintain a vertical orientation as they do. This means that more gets nicked off the sides each time than the top or bottom, and the henpei seimai goal is achieved. So anyone with the requisite skill and experience can do it, it just takes longer, and uses more energy as well.

This is obviously appealing to most brewers: remove a higher percentage of fat and protein with less milling. But since it is a hassle, most brewers do not do it. Yet, amongst those that do, Shin Nakano seems to be the machine of choice, (although that is based on observation and word on the street rather than hard statistics).

However: Satake came back into the mix by recently developing a new milling machine that can do Henpei Seimai, but without all the little adjustments that are normally called for. No mess, no stress. Just select “henpei” and it works. It does it faster as well, and uses less energy in doing so.

But they also took it a step further: Satake developed a slightly different milling outcome that they call Genkei Seimai. Genkei means “original shape,” and as can be surmised from the name, it purports to mill the rice in such a way that it ends up closer to the original shape than normal round milling or Henpei Seimai. The result is that there is more fat around the middle than Henpei, but less than regular milling. However, there is less cracking and breaking since the original natural shape remains more integrated.

They have, in fact, just introduced this machine and this way of milling, so there are not enough results in the field to develop an opinion. That will come, and we will look at some preliminary mumblings in a moment. But to me, the most significant thing about all this is that the mighty Satake is actively getting involved in the sake rice milling game again. That bodes quite well for the sake world.

Back to the differences between the milling methods, please refer to the drawing. Regular milling takes a rugby ball and mills it into the shape of a baseball, Henpei Seimai mills more from the fat-laden sides than the ends, and Genkei Seimai is less flat, and mills somewhere in the middle, with the objective being maintaining the original dimensions, so to speak, of the rice grain.

Back to the differences between the milling methods, please refer to the drawing. Regular milling takes a rugby ball and mills it into the shape of a baseball, Henpei Seimai mills more from the fat-laden sides than the ends, and Genkei Seimai is less flat, and mills somewhere in the middle, with the objective being maintaining the original dimensions, so to speak, of the rice grain.

Several breweries in Hiroshima cooperated with Satake to brew sake that were identical in every way other than one being milled using Henpei Seimai and the other using the newfangled Genkei Seimai. One of them was Imada Shuzo, brewers of Fukucho. The owner/toji, Ms. Miho Imada, sent me a bottle of each to do the comparison.

In truth, I only had one bottle of each, and both were freshly pressed and nama. While certainly delicious, I might be able to tell a bit more with some time in the bottle and pasteurization, but that chance will come in time. And from what I tasted, the results were as subtle as might be expected considering how slight the differences in milling are.

The Genkei Seimai sake seemed sharper and brighter in aromas, but more settled, broader and rounder in flavor. The Henpei Seimai  seemed richer in aromas but lighter in flavor. While I am not sure why the aromas were that way, knowing that Henpei was brewed with rice with a bit less fat and protein, the slightly slimmer flavor seemed appropriate. But again, we would need another hundred samples or so to come up with a truly dependable result.

seemed richer in aromas but lighter in flavor. While I am not sure why the aromas were that way, knowing that Henpei was brewed with rice with a bit less fat and protein, the slightly slimmer flavor seemed appropriate. But again, we would need another hundred samples or so to come up with a truly dependable result.

After having brewed with all three types of milled rice, regular, Henpei and Genkei, Ms. Imada emphasized one thing quite emphatically.

“None of these methods is unequivocally better than the other. None will replace the other two; they all have their place. It depends on what kind of sake you want to brew; that’s the deciding factor.”

And, as mentioned above, to me what is most important is that these developments continue to take place, and that important companies like Satake continue be involved at the research and product development levels.

If you are in Japan, you can purchase both sake here and compare for yourself: https://fukucho.info/?mode=cate&cbid=2467869&csid=0

If you are interested the machine that does it, you can see the specs here, in Japanese: https://satake-japan.co.jp/products/ricemill/sake/edb40a.html

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Interested in learning more about sake, and the industry in Japan that makes it? Subscribe to Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Learn more and read a few sample issues here.

Sake brewing today has become very scientific. But long ago, before the days of thermometers, hydrometers, and barometers, brewers relied entirely on their five senses to gauge the progress of a fermenting tank of sake. As a curious side note, one toji told me that they compared the accuracy of some of the old school guys to that of modern instruments, and that the old toji of yesteryear were just as accurate as the modern equipment. Not sure this has been scientifically documented, but it is a great anecdote.

Sake brewing today has become very scientific. But long ago, before the days of thermometers, hydrometers, and barometers, brewers relied entirely on their five senses to gauge the progress of a fermenting tank of sake. As a curious side note, one toji told me that they compared the accuracy of some of the old school guys to that of modern instruments, and that the old toji of yesteryear were just as accurate as the modern equipment. Not sure this has been scientifically documented, but it is a great anecdote. of the tank. But soon after this the ferment will enter its most active stage, and foam will rise in great swaths, so that it looks like huge rocks tumbling over each other. This is known as iwa-awa (rock foam).

of the tank. But soon after this the ferment will enter its most active stage, and foam will rise in great swaths, so that it looks like huge rocks tumbling over each other. This is known as iwa-awa (rock foam). After this foam, too, fades away, the surface of the moromi is referred to as ji, or ground. This stage has many sub-conditions with their own names. Small wrinkles in the surface are referred to as chiri-men (a type of rough cloth). A totally smooth surface is known as bozu, in reference to the shaved head of a priest. If rice solids that did not ferment have risen to the surface, it may look like a lid is on the moromi, and this is referred to as futa (lid).

After this foam, too, fades away, the surface of the moromi is referred to as ji, or ground. This stage has many sub-conditions with their own names. Small wrinkles in the surface are referred to as chiri-men (a type of rough cloth). A totally smooth surface is known as bozu, in reference to the shaved head of a priest. If rice solids that did not ferment have risen to the surface, it may look like a lid is on the moromi, and this is referred to as futa (lid). Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

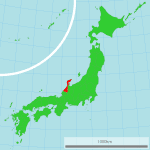

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today.

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today. eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate.

eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate. Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

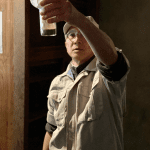

Next, to be doubly certain, he soaked the next basked fifteen seconds longer; it ended up at 33 percent. To wrap it up, he soaked the third basket fifteen seconds shorter; not surprisingly it ended up at 31 percent. He then instructed the other workers to soak the remaining few dozen baskets for nine minutes, exactly, and stepped aside to lead us on a tour of the rest of the kura.

Next, to be doubly certain, he soaked the next basked fifteen seconds longer; it ended up at 33 percent. To wrap it up, he soaked the third basket fifteen seconds shorter; not surprisingly it ended up at 31 percent. He then instructed the other workers to soak the remaining few dozen baskets for nine minutes, exactly, and stepped aside to lead us on a tour of the rest of the kura. he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances. the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role?

the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role? And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone.

And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone. company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy.

company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy. While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity.

Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity. harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.”

harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.” Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle.

Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle.