Certainly, change pretty much defines our world today, and the sake brewing world is not excepted from that truth. In particular, the changes within the sake world over the last 30 years in who actually does the brewing are pretty astounding.

There is one master brewer per brewery, and that person is called the toji. Almost always this was – and is – man, but currently perhaps 40 or 50 out of the 1100 or 1200 active kura have a toji that is a woman.

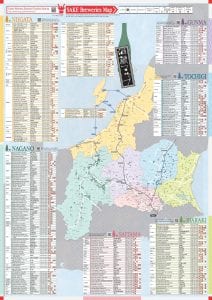

But long ago – and not so long ago – the toji in any given brewery was dispatched from his guild in the countryside. There were about 30 to 35 toji guilds across Japan long ago, although many of them are now defunct as their membership declined along with the number of breweries.

But back in the day, the toji was a seasonal employee. He may have worked at the same brewery every year for decades and decades, but each year was a new, one-year contract. Originally, the toji would receive a chunk of money from the brewery owner, and he would hire and pay everyone else, buy the rice, and just get the job done. That was not really a hard and fast rule, but even as recently as 30 years ago, most breweries in the industry were run by seasonally employed toji.

Slowly things changed. The need for year-round employment led to changes that included toji and brewing staff more commonly becoming year-round employees of the brewing company, replete with the benefits, like a paycheck in twelve rather than only six months of the year. When not brewing, other tasks could be handled, or hours could be seasonally juggled.

Another change included members of the brewery-owning family to take over the brewing themselves. Sometimes this was out of interest and passion, other times out of necessity. It is hard to run a small family business when all of the technical skill for creating your product is in the hands of someone that is but a seasonal hire, and not even a member of the family.

So what this led to is basically three genre of toji: those there are only seasonally employed toji from one of the guilds, toji that are year-round company employees, and toji that are family members. Note, too, that there is some overlap. Toji coming in from the countryside can be from the traditional guilds, but still be full-time employees (not just seasonal employees). And conversely, family members and local hires can be associated with one of the guilds in the boonies, for educational and informational exchange and support.

So what this led to is basically three genre of toji: those there are only seasonally employed toji from one of the guilds, toji that are year-round company employees, and toji that are family members. Note, too, that there is some overlap. Toji coming in from the countryside can be from the traditional guilds, but still be full-time employees (not just seasonal employees). And conversely, family members and local hires can be associated with one of the guilds in the boonies, for educational and informational exchange and support.

With that as the background, let us look at some very interesting numbers.

Thirty-two years ago, in 1986, 74 percent of the toji in the (then, much larger) industry were seasonal hires, not full-time employees. In 1996, a scant 10 years hence, that number had dropped to 62 percent. In 2006 it had dropped to 35.5 percent, and in 2016 it was down to only 16 percent of all breweries in the industry that had seasonally employed toji from the traditional guilds. Wow.

Note that this is not necessarily a bad thing; it is just … different. The industry is half the size of what it was back then, and the percentage of toji that are seasonal employees is a quarter of what it used to be. And whether or not a toji is seasonally hired or not has no direct influence on his or her skills, nor the quality of the sake. I’m just sayin’.

Looking at the other side of the toji coin, in 1986 only 12 percent of the toji in the industry had secure, year-round employment with the company. Sparing you the gory details of the decades in between, toji that are year-round full time employees went from that to 38 percent in 2016. And toji that are a member of the owning family went from a mere 14 percent in ’86 to a whopping 47 percent in 2016.

What this means, at a glance, is that almost half of the 1100 to 1200 sake breweries active today have family members in charge of the brewing operations.

Again, bear in mind there are several dynamics at work simultaneously, and that looking at the above number alone will not lead to any firm conclusion. One thing that has led to this is a very positive thing: the availability of reference material, education opportunities, and the infrastructure that allows almost instant communication. No longer does a brewery-owning family need to rely on an old codger from the boonies with a thick country accent. Just send the kids to brewing school, and keep in touch with friends running other breweries. That flow of information, and lots of patience and experience, is very commonly how sake is brewed in this modern era.

Again, bear in mind there are several dynamics at work simultaneously, and that looking at the above number alone will not lead to any firm conclusion. One thing that has led to this is a very positive thing: the availability of reference material, education opportunities, and the infrastructure that allows almost instant communication. No longer does a brewery-owning family need to rely on an old codger from the boonies with a thick country accent. Just send the kids to brewing school, and keep in touch with friends running other breweries. That flow of information, and lots of patience and experience, is very commonly how sake is brewed in this modern era.

Nevertheless, it is interesting, and surely, there are at least a few out there that will feel a nostalgic pang at the decline and loss of the tradition-laden historical guilds, myself included.

Learn much, much more about toji guilds here.

For those that are interested, the brewery workers under the toji are called kurabito, the brewery-owning family and family members are called kuramoto, and the brewery itself is a kura or sakagura.

~~~ ~~~ ~~~

The Sake Professional Course scheduled for April 23 to 25 in Brooklyn New York is full. Thanks to all those that signed up! The next one will be in Miami in September. If interested, please send an email to that purport to sakeguy @ gol.com. Learn more about the Sake Professional Course here.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me.

Al Gizzi likely never thought his legacy would live on in quite this way. And he surely never considered that he would be associated with sake. Al Gizzi does not even likely remember me. bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable.

bottle. Another is made by jacking sake with carbon dioxide. Everything in the Universe has a price, and this includes bubbles in your sake. That price is paid from the coffers of flavor. Much of this sparkling sake has an alcohol content of about eight percent, yet others are up around 14 percent. To me, it generally tastes like spiked cream soda; it is just the size of the spike that differs. But admittedly cream soda has its appeal too, and sparkling sake can be very drinkable. Kijoushu

Kijoushu Mr. Naohiko Noguchi is one of the most decorated, respected, accomplished and famous toji (master brewers) in the history of the sake brewing industry. And at 84 years of age, he is coming out of retirement for the fourth time to brew sake at a new brewery starting up next month. At 84. That’s eighty-four. As in LXXXIV. As in “hachijuyon.” One would think enough is enough; not for some folks.

Mr. Naohiko Noguchi is one of the most decorated, respected, accomplished and famous toji (master brewers) in the history of the sake brewing industry. And at 84 years of age, he is coming out of retirement for the fourth time to brew sake at a new brewery starting up next month. At 84. That’s eighty-four. As in LXXXIV. As in “hachijuyon.” One would think enough is enough; not for some folks. Brewer Number One stood up and faced the crowd. And he talked about his sake. Its lively yet balanced nature is the result of a family of yeasts, one of which was discovered at his brewery several decades ago, he explains. It has contributed to – if not created – the high reputation enjoyed by all of the sake in that region, which only came into sake prominence about 30 years ago.

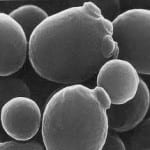

Brewer Number One stood up and faced the crowd. And he talked about his sake. Its lively yet balanced nature is the result of a family of yeasts, one of which was discovered at his brewery several decades ago, he explains. It has contributed to – if not created – the high reputation enjoyed by all of the sake in that region, which only came into sake prominence about 30 years ago. Yeast is massively important to the making of great sake. While they contribute to aromas more than anything else, good yeasts will also ferment strongly and not peter out too early, tolerate high levels of alcohol, yield appropriate levels of acidity that are not too high nor low, and much more.

Yeast is massively important to the making of great sake. While they contribute to aromas more than anything else, good yeasts will also ferment strongly and not peter out too early, tolerate high levels of alcohol, yield appropriate levels of acidity that are not too high nor low, and much more.