Three Significant Days in Sacramento, CA: The Iida Group Sake Brewing Seminar

There was, in late June, in Sacramento California, an unprecedented event: a seminar ran by a very prominent player in the Japanese sake-making world. It was a seminar taught by Japanese master sake brewers for the 15 or so craft sake producing companies in North America. It was, as might be expected, very, very cool. The seminar was run by a company called Iida Shoji that has a significant presence in the industry, and one that is steadily growing. The company owns a few sake breweries, so they are involved at that level. But they also run a company called Shin-Nakano, which makes rice milling machines.

There was, in late June, in Sacramento California, an unprecedented event: a seminar ran by a very prominent player in the Japanese sake-making world. It was a seminar taught by Japanese master sake brewers for the 15 or so craft sake producing companies in North America. It was, as might be expected, very, very cool. The seminar was run by a company called Iida Shoji that has a significant presence in the industry, and one that is steadily growing. The company owns a few sake breweries, so they are involved at that level. But they also run a company called Shin-Nakano, which makes rice milling machines.

In fact, Shin-Nakano makes rice milling machines only for sake production, i.e. not for rice in general. So they have a niche, and they have it sewed up tightly. Interestingly, to bolster their significance as the “rice milling machine of choice” for sake brewers, they present lots of research on techniques, methods and trends for modern sake as related to rice milling. And on top of all that, the employees seem open, light-hearted, and innovative.

The event was held in Sacramento since that is where Shin-Nakano has a rice milling plant. The region produces a lot of rice, and much of that is used in sake brewing in the US, which makes four times as much sake as is imported.

Iida Shoji reached out to and garnered participation from 14 small craft brewers in the US and Canada. While the five large breweries were mostly not in attendance, I am sure they were there in spirit. Also, by my count, there were six small breweries that for one reason or another were not present. I say that to point out that there are about 20 small craft sake breweries in the US now, in various phases of existence, running from “inactive” to “kicking ass.” And most were present.

While there were tastings and a party or two, as well as a visit to a craft sake brewery in San Francisco (Sequoia Sake), as well as a massive rice milling site, the heart of the seminar was a series of  lectures by three sake brewers that came over from Japan: Kosuke Kuji of Nanbu Bijin brewing their eponymous sake in Iwate, Philip Harper of Kinoshita Shuzo brewing Tamagawa sake in Kyoto, and Junpei Komatsu of Komatsu Shuzo, brewing Houjun sake in Oita. Each had a different angle, a different background, and different styles of sake.

lectures by three sake brewers that came over from Japan: Kosuke Kuji of Nanbu Bijin brewing their eponymous sake in Iwate, Philip Harper of Kinoshita Shuzo brewing Tamagawa sake in Kyoto, and Junpei Komatsu of Komatsu Shuzo, brewing Houjun sake in Oita. Each had a different angle, a different background, and different styles of sake.

There were also panel discussions with all three, and lectures on rice growing and distribution in the US as well.

Philip Harper is the toji (chief brewer) making Tamagawa, a rich sake with a clean finish; it is a very expressive yet traditional style. He has been brewing sake since like 1993, I think. Kosuke Kuji is the larger-than-life, with an always cheerful, vocal and energetic presence and spirit. He is the president of Nanbu Bijin, but very, very technically adept and excellent at conveying information. Junpei Komatsu restarted his brewery up after 20 years of dormancy. He began with very small batches at first, which made his perspective especially relevant to the attendees.

The seminar began with each brewer speaking in generalities about sake brewing and their observations of how everyone in North America was doing with their sake brewing. Later, it broke down into specific points and questions asked by the participants.

I am not a brewer, but hey, how could I not be there? From my slightly detached viewpoint, here were the main points. Most of these were echoed by all three lecturers, although each one emphasized different facets.

First, emphasized one brewer, figure out what kind of sake you want to brew. Don’t just try to make something drinkable, or not too bad. Decide if you want to make a rich sake, a light sake, an aromatic sake or a acid-driven wine-like sake. Or something altogether different. That will determine absolutely everything about your operation, so thnk about it well, and decide with commitment.

First, emphasized one brewer, figure out what kind of sake you want to brew. Don’t just try to make something drinkable, or not too bad. Decide if you want to make a rich sake, a light sake, an aromatic sake or a acid-driven wine-like sake. Or something altogether different. That will determine absolutely everything about your operation, so thnk about it well, and decide with commitment.

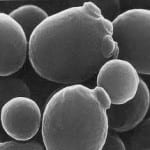

Next, sanitation. Be uptight, meticulous and fastidious about cleaning everything, all the time. This alone, it was emphasized, will very much improve the quality of your sake. Keep the bad bacteria out at all costs. Let the good micro organisms work in peace. (To me, this is the hugest difference between US and Japanese sake brewers.)

Also, all three emphasized that brewing will be different for each and every person at each and every venue. So you have to figure out what works for you, at your place. You have to “write your own textbook,” from experience and intention.

There were countless other small, detailed, technical questions and discussions, and what was great to me was that overall big issues like sanitation that would supersede smaller things like choice of rice or koji mold or yeast were covered, but the small and minutely detailed questions were answered as well. The balance was as fine as any great daiginjo.

The seminar was significant because it was the first time a representative of the sake industry in Japan proactively acted to help sake brewing efforts overseas. I have long observed the industry in Japan encouraging sake brewing overseas, showing interest and support. As more brewers overseas try their hand, more people will become familiar with sake and willing to try it and learn more about it. And this in turn will help the industry in Japan. It’s pretty much win-win. But this was the first time I have seen such a concrete and effective event take place. It was great.

The seminar was significant because it was the first time a representative of the sake industry in Japan proactively acted to help sake brewing efforts overseas. I have long observed the industry in Japan encouraging sake brewing overseas, showing interest and support. As more brewers overseas try their hand, more people will become familiar with sake and willing to try it and learn more about it. And this in turn will help the industry in Japan. It’s pretty much win-win. But this was the first time I have seen such a concrete and effective event take place. It was great.

A month later I ran into someone from Iida Shoji, one of the people most actively involved in putting the three-day seminar together. I congratulated him on its success.

“I look forward to attending next time, too!” I said.

“Hm…maybe two years from now. Not next year,” he replied.

“Oh, really? Not every year,” I teased.

A quick flash of exasperation on his face indicated just how much effort he and his company had put into it. It was clear they would need a break of about two years.His audible sigh augmented his expression.

“See you in two years.”

3. You will become eligible for the Level II Course, with Advanced Sake Professional certification testing, held in Japan in February of each year, from which only about 220 people have graduated.

3. You will become eligible for the Level II Course, with Advanced Sake Professional certification testing, held in Japan in February of each year, from which only about 220 people have graduated.

In May, the 105th Zenkoku Shinshu Kanpyoukai was held in Japan. The official English name for this contest is the Japan Sake Awards, but the literal translation is much more descriptive if slightly unwieldy: the National New Sake Tasting Competition. It is the longest running competition of its kind anywhere in the world. Those interested can find more information in the archives of this newsletter (which go back to 1999!), in particular in the June or July editions for each year.

In May, the 105th Zenkoku Shinshu Kanpyoukai was held in Japan. The official English name for this contest is the Japan Sake Awards, but the literal translation is much more descriptive if slightly unwieldy: the National New Sake Tasting Competition. It is the longest running competition of its kind anywhere in the world. Those interested can find more information in the archives of this newsletter (which go back to 1999!), in particular in the June or July editions for each year.

Several years ago, in July of 2014, the Yamagata Prefecture Sake Brewers’ Association began the process of securing a designation of their sake as a Geographical Indication recognized by the World Trade Organization and various international treaties. In order to qualify for something like this, a product (any product applying for a GI) must possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin. Securing such a designation gives the region and its producers the exclusive right to an appropriate indication on the label.

Several years ago, in July of 2014, the Yamagata Prefecture Sake Brewers’ Association began the process of securing a designation of their sake as a Geographical Indication recognized by the World Trade Organization and various international treaties. In order to qualify for something like this, a product (any product applying for a GI) must possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin. Securing such a designation gives the region and its producers the exclusive right to an appropriate indication on the label. public hearing on the topic on October 19 of this year. It was not made clear how long this stage will take, but assuming it does pass smoothly, Yamagata Sake will come into existence as a bona fide Geographical Indication (GI) for sake. One more region in Japan, the city of Hakusan in Ishikawa Prefecture, has qualified for a GI for the sake of that region. However, it only applies to the five breweries in city of Hakusan; the rest of the breweries in Ishikawa Prefecture are unaffected. Yamagata Prefecture will be the first entire prefecture to secure this distinction.

public hearing on the topic on October 19 of this year. It was not made clear how long this stage will take, but assuming it does pass smoothly, Yamagata Sake will come into existence as a bona fide Geographical Indication (GI) for sake. One more region in Japan, the city of Hakusan in Ishikawa Prefecture, has qualified for a GI for the sake of that region. However, it only applies to the five breweries in city of Hakusan; the rest of the breweries in Ishikawa Prefecture are unaffected. Yamagata Prefecture will be the first entire prefecture to secure this distinction.