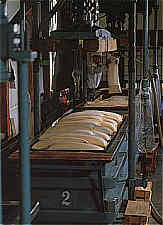

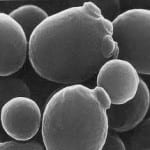

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake.

Koji is perhaps the most enigmatic component of the sake world. The absolute coarsest definition of koji is “moldy rice,” although that does not come close to doing it justice. “Steamed rice onto which the mold aspergillus oryzae has been painstakingly propagated over two days” is a much more eloquently crafted albeit wordy description. But no matter how you define it, without koji there would be no sake.

We are reminded of its importance all the time. “Ichi-koji, ni-moto, san-tsukuri.” First in importance is the koji, second is the yeast starter, and third is the fermenting mash. Indeed, nothing exerts more leverage on how a given batch of sake will turn out than the koji. The way a brewer makes the koji will determine if the sake is sweet, dry, rich or light.

How does it do that? Basically by providing enzymes that convert starch to sugar, allowing the yeast to ferment it, and also by contributing a whole host of other things like amino acids and more that combine and interact to become the backbone of the flavor profile of a given sake. But the process is fraught with peril as well: make the koji less than perfectly and the resulting sake could be thin, stinky in any one of oh-so-many ways, or cloying.

Actually, at least scientifically, sake can be made without koji. Straight enzymes can be used, and rice can be liquified. But there are some legal requirements in place that specify that at least some koji must be used. But legal stipulations notwithstanding, the koji drives everything about how a sake is made, and how it will taste and smell. More attention to detail goes into the koji than any other step of the process.

There is a semi-retired sake consultant I run into all the time at tastings, let’s just call him Dr. T., who used to be a government assessor. Tasting sake was basically what he did – as a career. Folks like that can taste a sake and tell a brewer just what they can do in the process to make it better, and this guy was one of the best.

But lately he seems perpetually disappointed in almost everything he tastes. Surly, almost. When I run into him at tastings, we will great each other cheerfully, after which he launches into a rant something along the lines of “No one here knows how to make koji properly…”

One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.)

One of the breweries under his care when he was active was Kusumi Shuzo in Niigata, who make the sake Kiyoizumi (among other brands). It’s a sake from Niigata that I do not get to taste often enough. The company is famous in the industry as the brewery that revived the rice Kame-no-o, or at least the first widely-used manifestation of it. (It’s complicated both botanically and legally; but I digress.)

Their sake is perhaps just a bit richer than most sake from Niigata, and Kusumi-san, the owner / president ascribes that to the importance they place on the koji. He insists that they do it he old way, “properly,” and that is what makes their sake what it is. The last time I spoke to him at a yearly distributor’s tasting, he spoke of “ listening to the koji.”

“You have to listen to the koji,” he began. “If you listen to the market, to consumers or to other stuff too much, they’ll tell you what they like and that can take a brewer away from the basics.” He made it seem a bit like populism in sake brewing.

“So, we don’t do that anymore. Instead, we listen to the koji.” What he meant, of course, was that regardless of what other brewers might be doing to please the aroma-loving public, they stuck to their traditional basics, centered as they were around making proper koji. By doing so, he continued, they would stay true to their style and would be able to continue to make the great sake they have always made.

He continued, with conviction and pride, “When people that really understand sake go to the store to buy our sake, they actually go out of their way to look at the date on the bottle and buy the oldest bottle on the shelf.” I dunno; a bit of hyperbole methinks. But his point is not lost on me; in fact, it is well taken.

“Because we listen to the koji as we make the sake, we know it will not only stand the test of time in the bottle, but actually be better because of it. We can’t be leaving it up to the yeast, you know. It’s the koji.”

That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.

That last little bomb about “not leaving it up to the yeast” was significant. He was subtly referring to how many modern popular sake are made using yeasts that yield prominent aromatics. While that is of course fine, sake like that does not age well; the compounds that lead to apple and tropical fruit nuances do not age gracefully. Often they become bitter and harsh. Age can do that.

But he was delicately and deftly stating how they do not just jump on the bandwagon of recently popular sake, and restating his commitment to their own way of brewing. “It’s the koji.”

Actually, making great sake is more than the koji. It’s, well, everything. Water, rice, technique, ad infinitum. But koji tops the list of priorities for minute attention to detail for a reason. And while it may be enigmatic to we mortals, that’s fine as long as the brewers understand it.