Five crucial elements are involved in brewing sake — water, rice, technical skill, yeast, and land / weather. More than anything else, sake is a result of a brewing process that uses rice and lots of water.

In fact, water comprises as much as 80% of the final product, so fine water and fine rice are natural prerequisites if one hopes to brew great sake. But beyond that, the technical skill needed to pull this all off lies with the toji (head brewers), the type of yeast they use, and the limitations entailed by local land and weather conditions. Please visit the links shown above for a detailed review of the crucial ingredients.

Quick overview

Rice is washed and steam-cooked. This is then mixed with yeast and koji (rice cultivated with a mold known technically as aspergillus oryzae). The whole mix is then allowed to ferment, with more rice, koji, and water added in three batches over four days. This fermentation, which occurs in a large tank, is called shikomi. The quality of the rice, the degree to which the koji mold has propagated, temperature variations, and other factors are different for each shikomi. This mash is allowed to sit from 18 to 32 days, after which it is pressed, filtered and blended. This would be enough to get you through most conversations. But let us look at the main steps and processes a bit more closely.

Rice Milling

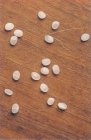

Note the white opaque starch packet in the center of many of the grains.

Note the white opaque starch packet in the center of many of the grains.

After proper sake rice (in the case of premium sake, anyway) has been secured, it is milled, or polished, to prepare it for brewing good sake. This is not as simple as it might sound, since it must be done gently so as to not generate too much heat (which adversely affects water absorption) or not crack the rice kernels (which is not good for the fermentation process). In the photo on left, the rice in top left corner is unmilled, the rice next to it has only 70% of kernel remaining, while the rice at bottom has been milled so only 35% remains. The photo at top right (with red background) shows rice ground to 50%. The amount of milling greatly influences the taste. For more on this topic, please visit Types of Sake page.

Washing and Soaking

Next, the white powder (called nuka) left on the rice after polishing is washed away, as this makes a significant difference in the final quality of the steamed rice. (It also affects the flavor of table rice; try washing your rice very thoroughly and notice the difference in consistency and flavor.) Following that, it is soaked to attain a certain water content deemed optimum for steaming that particular rice. The degree to which the rice has been milled in the previous step determines what its pre-steaming water content should be. The more a rice has been polished, the faster it absorbs water and the shorter the soaking time. Often it is done for as little as a stopwatch-measured minute, sometimes it is done overnight.

Next, the white powder (called nuka) left on the rice after polishing is washed away, as this makes a significant difference in the final quality of the steamed rice. (It also affects the flavor of table rice; try washing your rice very thoroughly and notice the difference in consistency and flavor.) Following that, it is soaked to attain a certain water content deemed optimum for steaming that particular rice. The degree to which the rice has been milled in the previous step determines what its pre-steaming water content should be. The more a rice has been polished, the faster it absorbs water and the shorter the soaking time. Often it is done for as little as a stopwatch-measured minute, sometimes it is done overnight.

Steaming

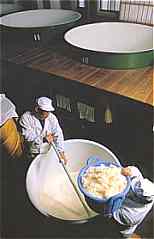

Next the rice is steamed. Note this is different from the way table rice is prepared. It is not mixed with water  and brought to a boil; rather, steam is brought up through the bottom of the steaming vat (traditionally called a koshiki) to work its way through the rice. This gives a firmer consistency and slightly harder outside surface and softer center. Generally, a batch of steamed rice is divided up, with some going to have koji mold sprinkled over it, and some going directly to the fermentation vat. (Photo at left: rice steaming in koshiki, or vat).

and brought to a boil; rather, steam is brought up through the bottom of the steaming vat (traditionally called a koshiki) to work its way through the rice. This gives a firmer consistency and slightly harder outside surface and softer center. Generally, a batch of steamed rice is divided up, with some going to have koji mold sprinkled over it, and some going directly to the fermentation vat. (Photo at left: rice steaming in koshiki, or vat).

Koji Making (Seigiku)

This is the heart of the entire brewing process, really, and could have several chapters, if not books, written about it. Summarizing, k(LEFT) Koji being cultivated in small trays (Right) A grain of rice cultavated with koji mold (photos by Kenji Nachi)oji mold in the form of a dark, fine powder is sprinkled on steamed rice that has been cooled. It is then taken to a special room within which a higher than average humidity and temperature are maintained. Over the next 36 to 45 hours, the developing koji is checked, mixed and re-arranged constantly. The final product looks like rice grains with a slight frosting on them, and smells faintly of sweet chestnuts. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, and is always made fresh and used immediately. Therefore, any one batch goes through the “heart of the process” at least four times. (Photo: Koji being cultivated in small trays, and a grain of rice cultavated with koji mold).

This is the heart of the entire brewing process, really, and could have several chapters, if not books, written about it. Summarizing, k(LEFT) Koji being cultivated in small trays (Right) A grain of rice cultavated with koji mold (photos by Kenji Nachi)oji mold in the form of a dark, fine powder is sprinkled on steamed rice that has been cooled. It is then taken to a special room within which a higher than average humidity and temperature are maintained. Over the next 36 to 45 hours, the developing koji is checked, mixed and re-arranged constantly. The final product looks like rice grains with a slight frosting on them, and smells faintly of sweet chestnuts. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, and is always made fresh and used immediately. Therefore, any one batch goes through the “heart of the process” at least four times. (Photo: Koji being cultivated in small trays, and a grain of rice cultavated with koji mold).

The yeast starter (shubo or moto)

Photo at right: the moto, or shubo yeast starter, foaming away.

Photo at right: the moto, or shubo yeast starter, foaming away.

The moto, or shubo yeast starter, foaming away (Photo by Kenji Nachi)A yeast starter, or seed mash of sorts, is first created. This is done by mixing finished koji and plain steamed white rice from the above two steps, water and a concentration of pure yeast cells. Over the next two weeks, (typically) a concentration of yeast cells that can reach 100 million cells in one teaspoon is developed.

The Mash (Moromi)

After being moved to a larger tank, more rice, more koji and more water are added in three successive stages over four days, roughly doubling the size of the batch each time. This is the main mash, and as it ferments over the next 18 to 32 days, its temperature and other factors are measured and adjusted to create precisely the flavor profile being sought.

Pressing (joso)

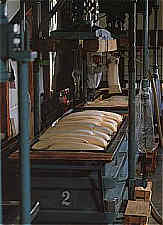

When everything is just right (no easy decision!), the sake is pressed. Through one of several methods, the white lees (called kasu) and unfermented solids are pressed away, and the clear sake runs off. This is most often done by machine, although the older methods involving putting the moromi in canvas bags and squeezing the fresh sake out, or letting the sake drip out of the bags, are still used. (Photo at right: bags of moromi from which sake is being drip-pressed. Below Photo: a fune, used for pressing sake out of bags of moromi).

When everything is just right (no easy decision!), the sake is pressed. Through one of several methods, the white lees (called kasu) and unfermented solids are pressed away, and the clear sake runs off. This is most often done by machine, although the older methods involving putting the moromi in canvas bags and squeezing the fresh sake out, or letting the sake drip out of the bags, are still used. (Photo at right: bags of moromi from which sake is being drip-pressed. Below Photo: a fune, used for pressing sake out of bags of moromi).

Filtration (roka)

After sitting for a few days to let more solids settle out, the sake is usually charcoal filtered to adjust flavor and color. This is done to different degrees at different breweries, and is goes a long way in dictating the style.

Pasteurization

Most sake is then pasteurized once. This is done by heating it quickly by passing it through a pipe immersed in hot water. This process kills off bacteria and deactivates enzymes that would likely adverse flavor and color later on. Sake that is not pasteurized is called namazake, and maintains a certain freshness of flavor, although it must be kept refrigerated to protect it.

Most sake is then pasteurized once. This is done by heating it quickly by passing it through a pipe immersed in hot water. This process kills off bacteria and deactivates enzymes that would likely adverse flavor and color later on. Sake that is not pasteurized is called namazake, and maintains a certain freshness of flavor, although it must be kept refrigerated to protect it.

Aging

Finally, most sake is left to age about six months, rounding out the flavor, before shipping. Before shipping it is mixed with a bit of pure water to bring the near 20 percent alcohol down to 16 percent or so, and blended to ensure consistency. Also, it is usually pasteurized a second time at this stage. It is somewhat unfair to the sake-brewing craft and industry to reduce sake brewing down to the short explanation above, but excessive detail would soon go beyond the scope of this book. The basics are as explained here.

Changes Over the Years

Over the centuries, naturally there were many adjustments and changes to the sake brewing process. These arose to either make better sake, or to make sake more economically. Sometimes, advances in the economic forum also lead to improved sake quality.

One of the most important advances was the improvement in rice-polishing equipment. Originally, rice was stomped on in a vat to remove the husks. Later, water wheels and grinding stones were used. Today, there are great computer-controlled machines that will polish off the specified percentage of the outside of the grains, and do it in a specified amount of time (with longer being better). This minimizes damage from friction heat and cracked grains.

Another major advance was the use of ceramic-lined or stainless steel tanks, now the standard, over cedar tanks, which were used for hundreds of years. This has drastically improved the quality and purity of sake since the beginning of this century.

Then there is the pressing stage. Until the early 1900s, all sake was pressed by pouring the moromi into canvas bags which were then put into a large wooden box called a fune. The lid was then cranked down into the box, squeezing out the sake. Now, almost all sake is pressed with a huge, accordion-like machine that squeezes the moromi between balloon-like inflating panels, making disposal of the lees (called kasu) simple.

Almost all breweries will still press some of their best sake in the old way, using a fune. It does indeed make subtly noticeably better sake. But the accordion-like machine (called an Assaku-ki) is so much more efficient, and the fune so labor intensive, that the tradeoffs are only worth it for top-grade sake.

Most controversially, however, is the koji making equipment. It is truly amazing how the slightest differences in koji can affect the flavor of the final product. Traditionally, koji is all made by hand in wood-paneled rooms kept warm and humid. As this is such a labor-intensive step, many changes have come about, and a lot of them are rejected later. (It is interesting to note that almost all super premium sake like daiginjo is made using hand-made koji.)

There are now large machines that will perform part or all of the koji making process, doing the work of several individuals. There are countless manifestations of these, all attempting to imitate the skill and intuition of the human masters. Other changes include stainless steel instead of wood walls. The risk of the development of unwanted mold is reduced, but humidity is affected. In the end, there are countless arguments for and against these changes. Subtle changes in daily temperature and rice quality may not always be picked up by machines but, for example, sanitation can be greatly improved. Naturally, technological progress to some degree is necessary for the industry to survive.

SAKE CONFIDENTAL

SAKE CONFIDENTAL

Interested in learning more about sake?

Check out my book “Sake Confidential” on Amazon.

Sake Confidential is the perfect FAQ for beginners, experts, and sommeliers.

Indexed for easy reference with suggested brands and label photos. Includes:

- Sake Secrets: junmai vs. non-junmai, namazake, aging, dry vs. sweet, ginjo, warm vs. chilled, nigori, water, yeast, rice, regionality

- How the Industry Really Works: pricing, contests, distribution, glassware, milling, food pairing

- The Brewer’s Art Revealed: koji-making, brewers’ guilds, grading

SAKE INDUSTRY NEWS

If you are interested in staying up to date with what is happening within the Sake Industry and also information on more advanced Sake topics then Sake Industry News is just for you!

Sake Industry News is a paid subscription newsletter that is sent on the first and 15th of each month. Get news from the sake industry in Japan – including trends, business news, changes and developments, and technical information on sake types and production methods that are well beyond the basics – sent right to your inbox. Subscribe here today!

Each issue will consist of four or five short stories culled from public news sources about the sake industry in Japan, as well as one or more slightly longer stories and observations by myself on trends, new developments, or changes within the sake industry in Japan.

There is plenty of immensely enjoyable sake not in the top of the top classifications. In fact, sometimes such sake has more presence, uniqueness, and appeal than super dooper hoity toity high priced daiginjo. Well, sometimes, anyway. Top of PageSake is almost always fairly priced.

There is plenty of immensely enjoyable sake not in the top of the top classifications. In fact, sometimes such sake has more presence, uniqueness, and appeal than super dooper hoity toity high priced daiginjo. Well, sometimes, anyway. Top of PageSake is almost always fairly priced. If you study the flavor profiles of sake from around Japan, you can easily see how well the local sake jibes with the original cuisine of the region. Sake from mountainous regions of Japan, like the Tohoku region in the north, is sturdier and more rice-laden in flavor, complementing well the salt-preserved and fermented flavors common in that region’s food. Sake from Shizuoka, Toyama and Miyagi are lighter and more supple, which works perfectly with the abundance of fresh fish found in these areas.

If you study the flavor profiles of sake from around Japan, you can easily see how well the local sake jibes with the original cuisine of the region. Sake from mountainous regions of Japan, like the Tohoku region in the north, is sturdier and more rice-laden in flavor, complementing well the salt-preserved and fermented flavors common in that region’s food. Sake from Shizuoka, Toyama and Miyagi are lighter and more supple, which works perfectly with the abundance of fresh fish found in these areas.