It all begins again…

Fall has fully entrenched itself, complete with its colors, cooler weather, and culinary delights. It is also the most significant time of the year for the sake world: the brewing season is about to begin.

Except for a few dozen brewing factories operated by the largest sake brewing companies, sake is brewed in the colder months, generally from the end of October to the beginning of April, give or take a few weeks each way. Sake fermentation takes place at lower temperatures, and as such cannot be sustained during other times of the year. Larger brewers have facilities that keep fermenting tanks cold all year round, and although the quality of sake brewed in such facilities can be just as high, breweries with these facilities constitute the exception and not the rule.

Except for a few dozen brewing factories operated by the largest sake brewing companies, sake is brewed in the colder months, generally from the end of October to the beginning of April, give or take a few weeks each way. Sake fermentation takes place at lower temperatures, and as such cannot be sustained during other times of the year. Larger brewers have facilities that keep fermenting tanks cold all year round, and although the quality of sake brewed in such facilities can be just as high, breweries with these facilities constitute the exception and not the rule.

Historically, tor taxation and accounting purposes, the sake-brewing year began October 1st of each year. (Currently, it is actually July 1.) Although this has always been the most practical time to begin, the shogun made it official in 1798 by dictating that no sake brewing was permitted before the Autumn Equinox. Stipends to samurai and taxes were paid in rice, and sake was brewed with what was left. Hey, first things first.

Much has changed over the last several centuries, yet much has remained the same. There are a number of *then and now* comparisons that can be made.

One thing that has not changed much is the connection between sake brewing and Japan’s indigenous religion, Shinto. Almost every brewery in the country has a small Shinto shrine on the grounds, and often a larger one nearby the brewery. At the beginning of the brewing season, the brewers, owner and other employees will gather with a priest for a ceremony to pray for a successful and safe brewing season. This takes place at even the largest breweries, amidst gleaming, modern equipment.

One thing that has not changed much is the connection between sake brewing and Japan’s indigenous religion, Shinto. Almost every brewery in the country has a small Shinto shrine on the grounds, and often a larger one nearby the brewery. At the beginning of the brewing season, the brewers, owner and other employees will gather with a priest for a ceremony to pray for a successful and safe brewing season. This takes place at even the largest breweries, amidst gleaming, modern equipment.

Until a scant few years ago, kurabito (brewers) and toji (brewmasters) were almost exclusively farmers from the rice-growing countryside with no work in the winter. They would travel a fair distance from their homes and live in the brewery throughout the six month brewing season. This is an integral part of how the culture of the sake world developed.

To some degree, this is still the case today. Most brewing personnel are fairly advanced in age, and still make the trek each season to live away from home. But things are indeed rapidly changing. It has become painfully obvious to the industry that young blood is desperately needed. As such, most places now use some local people as brewers, normal folk that go home at night to their families and in a few instances even punch a time clock.

To some degree, this is still the case today. Most brewing personnel are fairly advanced in age, and still make the trek each season to live away from home. But things are indeed rapidly changing. It has become painfully obvious to the industry that young blood is desperately needed. As such, most places now use some local people as brewers, normal folk that go home at night to their families and in a few instances even punch a time clock.

Most kura actually use a bit of a hybrid system, in which the oldest and most experienced brewers and the toji are experienced journeymen from the countryside living in the brewery, but the heirs apparent, the next generation of brewers, are young and local. It is a phase of transition to the future of sake.

Still, many young brewers find it difficult to relate to their older sempai, and quit under the pressure of the harsh, feudalistic treatment of old.

The presence of women in the brewery is another interesting then-and-now comparison. Until quite recently, the presence of women in the brewery was anathema. Bizarre beliefs (or excuses expressed as such) dictated that the mere presence of a female amidst the fermenting tanks would cause all kinds of problems, both technical and psychological.

While many older male brewers still have some resistance to women in the kura today, many breweries have women helping in the day to day brewing tasks. There are even a handful of toji that are women (23 as of last year).

Young or old, male or female, any day now the brewers will gather at their brewery and begin the arduous task of preparing for the season. The first couple of weeks involve nothing but cleaning. Sanitation is paramount, especially with the open fermentation methods of sake brewing. Everything will be scrubbed, cleaned and sanitized.

Young or old, male or female, any day now the brewers will gather at their brewery and begin the arduous task of preparing for the season. The first couple of weeks involve nothing but cleaning. Sanitation is paramount, especially with the open fermentation methods of sake brewing. Everything will be scrubbed, cleaned and sanitized.

Soon after, the milling of rice will begin, followed soon thereafter by the first batches of sake. Brewing begins with lower grades of sake. As the weather becomes progressively colder, higher grades of sake will be brewed, with the ginjo-shu brewing period peaking in January and February.

The inside of today’s sake breweries also contain a mix of ancient and modern. Much of the equipment is modern, things like boilers, fermentation tanks, and even the occasional computer. But much remains as it was long ago.

Most brewery buildings themselves are old, classic studies in Japanese architecture. Many of the brewing tools remain rudimentary. There are plenty of bamboo poles and brushes, and other implements fashioned from traditional materials, as they have yet to be bested by modern counterparts. Yet, mixed in with these tools of old are modern gadgets, everything from temperature sensors and automatic mixers to full-on koji making machines and conveyor belt driven continuous rice steamers. Each kura draws their own line on how much automation to use.

Yet, mixed in with these tools of old are modern gadgets, everything from temperature sensors and automatic mixers to full-on koji making machines and conveyor belt driven continuous rice steamers. Each kura draws their own line on how much automation to use.

Regardless, this time of the year holds great significance in the traditional sake-brewing world. And so, as the centuries-old traditional cycle begins again, let’s all hope for another safe and successful season.

酒 酒 酒

The next Sake Professional Course will take place in San Francisco on December 8 to 10. Learn more here.

The next Sake Professional Course will take place in San Francisco on December 8 to 10. Learn more here.

Meanwhile, the next Sake Professional Course in Japan will take place January 26 to 30, 2015. Learn more here.

Feel free to email me with questions about either!

– See more at the Sake Professional Course!

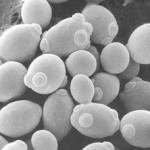

Back about 80 years ago when this organization was put together, they started to reproduce yeast that was known to be strong and predictable, and make it available to any brewer in the industry in little ampules. This helped ensure good sake, which led to good tax revenue. 😉

Back about 80 years ago when this organization was put together, they started to reproduce yeast that was known to be strong and predictable, and make it available to any brewer in the industry in little ampules. This helped ensure good sake, which led to good tax revenue. 😉 predecessors, it now may be giving Number 7 a run for the money in how commonly it is used.

predecessors, it now may be giving Number 7 a run for the money in how commonly it is used.