Non-foaming Yeasts

Admittedly, the subject of yeast types begins to push the envelope of geekdom. While some want to know both in theory and practice the difference between a Number 9 and a Number 10, and perhaps even between a CEL-24 and EK-1, most of us are content to sip and smile. Even so, there are some interesting historical, cultural and technical anecdotes surrounding even things as dryly scientific as yeast, and the topic of foamless yeasts, or “awanashi kobo,” is one such example.

Admittedly, the subject of yeast types begins to push the envelope of geekdom. While some want to know both in theory and practice the difference between a Number 9 and a Number 10, and perhaps even between a CEL-24 and EK-1, most of us are content to sip and smile. Even so, there are some interesting historical, cultural and technical anecdotes surrounding even things as dryly scientific as yeast, and the topic of foamless yeasts, or “awanashi kobo,” is one such example.

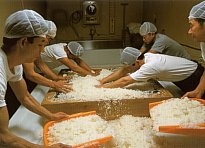

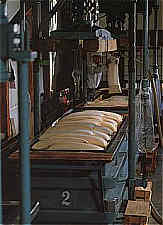

First of all, just what is foamless yeast? Usually, when sake undergoes its 20- to 40-day fermentation, the foam rises in great swaths and falls again, especially over the first third or so of this period. In fact, brewers of olde would judge the stage, progress and condition of a given batch by the appearance (and smell, and taste, and even sound) of this foam atop the fermenting mash. Also, there are ten times more yeast cells in the foam than the mash itself, so very often yeast for subsequent batches is removed from the foam of healthy, vibrantly fermenting tanks.

So foamless yeasts, obviously, are strains of yeast that do create as much foam (there still is a little bit) as they convert sugars to alcohol, carbon dioxide, and more. The question is, why would anyone want to use them?

There are, actually, a number of very good reasons. Most of these are centered around efficiency, sanitation, labor-savings, and even safety. For instance, since the foam rises so high during fermentation, brewers cannot fill a tank to the brim with rice, koji and water since it would soon overflow with foam, leading to hygienic nightmare. Rather, they can only fill the tank initially about 3/4 of the way to leave room for the foam to rise and fall. Naturally, this puts a damper on one’s yields and efficiency. There may be 30 tanks in a fermentation room, but if you can only fill each up 3/4 of the way, your monthly yields are only 75 percent of what they might be. With foamless yeasts, however, this concern is all but a non-issue, and a brewery can get the higher yields out of each batch and tank.

There are, actually, a number of very good reasons. Most of these are centered around efficiency, sanitation, labor-savings, and even safety. For instance, since the foam rises so high during fermentation, brewers cannot fill a tank to the brim with rice, koji and water since it would soon overflow with foam, leading to hygienic nightmare. Rather, they can only fill the tank initially about 3/4 of the way to leave room for the foam to rise and fall. Naturally, this puts a damper on one’s yields and efficiency. There may be 30 tanks in a fermentation room, but if you can only fill each up 3/4 of the way, your monthly yields are only 75 percent of what they might be. With foamless yeasts, however, this concern is all but a non-issue, and a brewery can get the higher yields out of each batch and tank.

Also, when foam does rise and fall, the remains that cling to the side of the tank are a veritable hotbed of bacterial activity, an orgy of undesirable microorganisms just hankerin’ to drop back in and do damage to the unsuspecting ambrosia-in-waiting below. So this must be assiduously cleaned off by the brewers. Not only is this hard and time consuming work, it is also quite dangerous, since it generally requires leaning into the tank. Falls into tanks are almost always fatal since there is no oxygen and the huge amount of carbon dioxide billowing up from the mash is harshly engulfing. So by eliminating the foamy remains, time, labor, and risk are spared. Finally, without all that gunk in the way, the hard-working yeast cells move and work a bit more freely, so that fermentation proceeds a smidgeon faster and can finish a day or two earlier.

Why are they foamless? What happens, it seems, is that most yeast cells will cling to bubbles of carbon dioxide that are created and then rise to the surface. Foamless yeast cells, on the other hand, for whatever reason do not cling to these bubbles and so are not carried up, up, and away. Since the bubbles are unencumbered, they pop, and there is no foam rising high above the mash.

The foamless yeasts that are commonly encountered out there today are non-foaming versions of the “usual suspects,” rather than being new, unknown, or total mutant life-forms.

Actually, they appear naturally and spontaneously. About one in every several hundred million yeast cells of a given type are foamless, but obviously, if just one in several hundred million is non-foaming, no one will notice. It just takes patience to isolate some and cultivate a pure culture of them.

Also, they have been around a long time, it seems, but proper records go back until only about 1916, when several breweries reported experiences with them. Apparently, until then, the brewers that encountered these thought, “Whoa. This can’t be right. Let’s just quietly throw this mutant away before anyone finds out about it. It could be bad for our rep and all.”

While foamless yeasts were used sparingly and experimentally for decades, the first commercial use of a foamless yeast was actually in Hawaii, believe it or not. In 1960 or 1961, a full ten years before it was used on anything remotely resembling a large scale in Japan, foamless yeasts were used by Takao Nihei of the Honolulu Sake Brewery. Dispatched by the brewing research organization within the government of Japan, he was the first to take what information there was on these yeasts (and a sample, of course) and run with it. His focus was saving labor and producing great sake with great efficiency, and this he did with great success.

While foamless yeasts were used sparingly and experimentally for decades, the first commercial use of a foamless yeast was actually in Hawaii, believe it or not. In 1960 or 1961, a full ten years before it was used on anything remotely resembling a large scale in Japan, foamless yeasts were used by Takao Nihei of the Honolulu Sake Brewery. Dispatched by the brewing research organization within the government of Japan, he was the first to take what information there was on these yeasts (and a sample, of course) and run with it. His focus was saving labor and producing great sake with great efficiency, and this he did with great success.

Are these foamless yeasts really the same as their bubbling counterparts, except for the foam? Most brewers say, “Yes, the results are essentially same, and the practical advantages make it a clear choice for us.” However, there are a still a few hardcore toji who insist that the foamless manifestations are not quite as good as the foaming yeasts. Naturally, the ability to gather information from the appearance of the foam is eliminated. Still, most brewers feel that with foamless yeasts they get the same quality of sake, with less mess.

Foamless yeasts, at least those distributed by the Brewing Society of Japan, are designated by a -01 after the normal nomenclature. So a foamless Number 7 is known as 701, foamless Number 9 as 901, and so on. Those you are most likely to come across these days are 701, 901, and 1801.

Brewers are not obligated to provide information on the choice of yeast used, but often do. While there are countless yeasts used in sake today, just a few are non-foaming, and now you can recognize them.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Sake Professional Course in Las Vegas October 28 to 30~~~~~~~~~~

The next Sake Professional Course will take place October 28 to 30 at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas Nevada. Finish off an intense sake education by spending Halloween in Vegas!

More about the seminar, its content and day-to-day schedule, can be found here:

http://www.sake-world.com/html/spclv.html

Kikizake-joko – Official Tasting Glasses

The Sake Professional Course, with Sake Education Council-recognized Certified Sake Professional certification testing, is by far the most intensive, immersing, comprehensive sake educational program in existence. The three-day seminar leaves “no sake stone unturned.”

The tuition for the course is $825. Feel free to contact me directly at sakeguy@gol.com with any questions about the course, or to make a reservation.

– See more at: http://sake-world.com/#sthash.cQKxZymO.dpuf