In the April issue of blog, archived here, I wrote comprehensively and effusively about Yamada Nishiki, the current king of sake rice varieties. It is the most widely grown, and – amongst the 100 or so sake rice varieties in use today – it most easily lets brewers make the best sake they can.

In the April issue of blog, archived here, I wrote comprehensively and effusively about Yamada Nishiki, the current king of sake rice varieties. It is the most widely grown, and – amongst the 100 or so sake rice varieties in use today – it most easily lets brewers make the best sake they can.

Note the choice of wording. That diction was chosen to represent what most brewers and sake professionals try to convey. Yamada Nishiki itself does not necessarily lead to great sake; however, in the hands of a good toji, it is much easier to make great sake using that rice than any other. While certainly there are many opinions, most would agree on this, methinks.

What that really implies is, in the end, the skill, intention and techniques employed by a brewer contribute more to the final nature of a sake than the choice of rice. But the rice is also an extremely important factor, as that allows the brewer to work his or her craft to the utmost.

Curiously, many a toji (master brewer) will insist that it is his or her main role is to create a good environment for the koji and yeast so as to allow the sake to brew itself, and then basically get out of the way. But even through that interpretation, great rice like Yamada Nishiki makes that job easier.

As much adulation as I lavished upon it a few months ago, there is more to say that is historically quite interesting. Let us look at that here.

Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors.

Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors.

And again: it is favored by brewers less for how it ends up tasting than for how it behaves and how it can be handled in the fermenting mash. For example, it dissolves at an ideal, manageable speed. If the rice breaks down and dissolves and ferments too quickly, it can lead to a lot of off-flavors. But if it does not dissolve fast enough, the flavor has no character, or breadth or depth. Neither extreme is good, and Yamada Nishiki walks that fine line.

Looking back, there are a number of events and political changes that brought about the phenomenon of Yamada Nishiki.

The first big change was in 1874, six years after the Meiji Restoration, when the government changed the way rice growers were taxed. Until that time, rice farmers paid taxes with rice itself; a certain chunk of all that one grew was shipped off to the government for their use.

But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop.

But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop.

Then, in 1893, the government undertook research to identify and develop strains of rice more conducive to modern times and cultivation methods.

They formed a national agricultural research center and gathered all the rice types from all the localities they could, selected from amongst them a lineup that was particularly good, and got going with the research. The next year, Hyogo Prefecture started their own version of that research center that aligned their work with that of the national government. They then started looking for varieties that would be suitable to be selected as main ones to be used in a wider expansion that would benefit Hyogo’s agricultural economy.

Still, as mentioned above, sake rice production was on the decline. Compared to the easy to sell table rice, sake rice was hard to grow, it is quite tall and therefore falls over easily, and yields per field are much lower. It therefore costs farmers more to grow it, and there is less of a market for it. So in order to secure the high quality sake rice they needed, the brewers of Nada (modern day Kobe and Nishinomiya cities in the same prefecture, Hyogo, where the largest breweries have been for 250 years) created a contractual system with the farmers in the region (then known as the Harima region, now just a part of Hyogo) to secure a stable supply at a price that made it worth it to the farming community.

Still, as mentioned above, sake rice production was on the decline. Compared to the easy to sell table rice, sake rice was hard to grow, it is quite tall and therefore falls over easily, and yields per field are much lower. It therefore costs farmers more to grow it, and there is less of a market for it. So in order to secure the high quality sake rice they needed, the brewers of Nada (modern day Kobe and Nishinomiya cities in the same prefecture, Hyogo, where the largest breweries have been for 250 years) created a contractual system with the farmers in the region (then known as the Harima region, now just a part of Hyogo) to secure a stable supply at a price that made it worth it to the farming community.

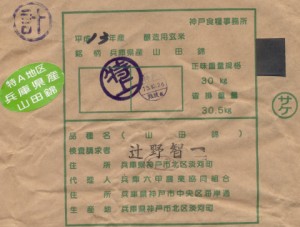

From about 1897, farmers and Nada brewers worked back and forth and hammered out these agreements that led to an system called muramai seido, which still exists to some degree today. It identified the best rice fields in Harima and set relative prices on rice from the surrounding fields as well. Once this was established, rice producing towns and villages or Harima began to sell their rice as a group, and the big brewers of Nada would purchase rice from those villages. This close cooperation helped the sake brewers to train and raise great rice farmers nearby. Note, though, that this all began even before Yamada Nishiki was created, and the rice from the Harima region was not as valued as it would later become.

Next, in 1912, the first rice varieties suitable for sake brewing that would promoted by the government as suitable for both large-scale cultivation and good for sake brewing (i.e. “sake rice”) were selected: Yamadaho and Wataribune. (Remember those names!)

Then in 1923, they manually crossbred Yamadaho and a version of Wataribune called Tankan Wataribune (“short-stalk” Wataribune) to create one strain that would be used for research. It was given the unglamorous name of Yama-watari 50-7 during that research stage. It did in fact get selected for as a rice the government would promote, and was in 1932 certified as a bona fide new rice type. Next it went into feasibility testing to assess its suitability to large scale production. Obviously, it passed, and was finally christened Yamada Nishiki in 1936.

However, it was not immediately recognized for its greatness and languished for a few years.

This is because the Nada brewers strongly preferred to use rice from what was then called the Hokusetsu region, which is now the northern part of neighboring Osaka Prefecture. They insisted it was softer and that it was easy to make koji using it. It was also considered to be fragrant and encouraged vigorous fermentation.

While this also may have been true, the truth is that they were very accustomed to the rice they had been using, and they were concerned that if they tried a new rice, it might be hard to get it to behave as they wanted to. It was easier to stick with what they knew. The risk of sake spoiling during fermentation, rendering the entire tank wasted, was higher in those days, and throwing another variable into the mix only increased the possibility of that happening.

Yamada Nishiki’s big break, so to speak, came in 1942, when the war necessitated rationing of rice. The rules surrounding this dictated that the brewers were not allowed to bring in rice from other prefectures, and had to use rice grown in their own prefecture. This seems natural considering the circumstances of the day.

So that meant that Nada brewers (remember, Nada is in Hyogo Prefecture, the next prefecture westward from Osaka) had to use Hyogo rice, not Osaka rice. And this meant that the brewers had no choice but to try this new Yamada Nishiki stuff from Hyogo.

Once they began to use it, though, they be like, “whoa, this stuff is good!” Using it, they found it was even easier to make good sake, and so turned their attention toward using increasingly more Yamada Nishiki. While it can be expensive, and while there are other great rice types, Hyogo-grown Yamada is still most brewers’ choice for at least their most extravagant sake.It has gradually grown in usage, but has always remained comparatively expensive. Although it is now the most widely grown sake rice, but it only took this lead in the mid-90s. Currently in Hyogo alone there are 5500 people growing it.

One reason it remains so good is that Hyogo growers take very good care of the DNA, so to speak. If one grows any rice and just haphazardly uses last year’s seeds to grow this year’s rice, pollen et al from other rice types will naturally get mixed in and the sake will lose its purity and its erstwhile main characteristics will become diluted. So at the sake rice research center in Hyoto, each and every seedling is inspected one at a time to be sure it has has maintained the original and necessary characteristics of Yamada Nishiki.

These are then grown to yield more seeds, which are then grown to yield even more seeds, that are then distributed to seed cooperatives, who then distribute the seeds to the farmers to use to grow the rice. So count ‘em: that is only three generations from purity each year, no seeds are any more than three generations from individually inspected and assessed purity. Dig that.

These are then grown to yield more seeds, which are then grown to yield even more seeds, that are then distributed to seed cooperatives, who then distribute the seeds to the farmers to use to grow the rice. So count ‘em: that is only three generations from purity each year, no seeds are any more than three generations from individually inspected and assessed purity. Dig that.

Of the myriad ways to enjoy sake, of course appreciating its flavors and aromas and its relaxing benefits are the most accessible. But the behind-the-scenes history, anecdotes and conversation fodder equally enjoyable. Well; almost.

Remember the roots of the rice the next time you enjoy Yamada Nishiki in a cup.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sake Professional Course in Japan

From Tuesday, January 10 through Saturday, January 14, I will hold the annual Japan-based running of the Sake Professional Course in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please send me an email to that purport.

More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available here, with a downloadable pdf there as well, and testimonials from past graduates can be perused here as well. The three-day courses wrap up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation for a future course, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available here, with a downloadable pdf there as well, and testimonials from past graduates can be perused here as well. The three-day courses wrap up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation for a future course, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity.

Way back in April of this year I was in London as a judge for the International Wine Challenge’s Sake Competition. On the morning of the third straight day of tasting sake, it was down to a few sake and a few judges. We were assessing whether or not the sake that had made the cut thus far were worthy of a gold, silver or bronze medal, or whether they were to be relegated back to the quagmire of mediocrity. harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.”

harvest rice, not a late-harvest rice, we should not expect much more out of it. This is about as rich or deep a profile as we can expect, and because it was a deliberate choice on the part of the brewer, we should acknowledge that and give it a medal.” Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle.

Most, but not all, sake rice tends to be okute; this includes Yamada Nishiki, Omachi and a few more well-known types. Gohyakumangoku is a typical example of a sake rice that is wase. And there are of course many rice varieties that are neither early nor late harvest, but rather somewhere in the middle.

From Monday, April 3 until Wednesday April 5, I will hold the first Sake Professional Course of 2017 at Bentley Reserve in San Francisco. If interested, for more information please send me an email at sakeguy@gol.com. “No sake stone remains left unturned” in this very comprehensive course. Learn more

From Monday, April 3 until Wednesday April 5, I will hold the first Sake Professional Course of 2017 at Bentley Reserve in San Francisco. If interested, for more information please send me an email at sakeguy@gol.com. “No sake stone remains left unturned” in this very comprehensive course. Learn more  In the April issue of blog, archived

In the April issue of blog, archived  Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors.

Before launching into its history and roots, let’s quickly review why it is significantly easier to make good sake using Yamada Nishiki. The grains are large, which means more potential for fermentable starch inside. The starches are concentrated in a ball of starch in the middle, and well centered, meaning it is easy to mill the outer fat and protein away, revealing only the starch. And, that protein and fat are at low levels to begin with, lowering the potential for off-flavors. But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop.

But after that change, tax was due in money based on the amount of land they owned. This means that all of a sudden rice was a commodity, a product to be sold on the marketplace that would lead to revenue to pay such taxes and cover living expenses and savings. As such, the more one grew the more one made, and farmers were all of a sudden very motivated to maximize yields and to do that by growing high-yield rice varieties. Sake rice varieties are decidedly not that kind of rice. So, even though demand for rice was increasing, the production of sake rice with its low yields began do prodigiously drop. More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available

More information about the course, the schedule, the syllabus and the fun is available

Sake is, as we all know, brewed from rice. Rice, in turn, is a very focused expression of soil, climate, and each year’s weather conditions such as sunshine, rain and typhoons. Every growing season is different, and there are good years for sake rice and bad years for sake rice.

Sake is, as we all know, brewed from rice. Rice, in turn, is a very focused expression of soil, climate, and each year’s weather conditions such as sunshine, rain and typhoons. Every growing season is different, and there are good years for sake rice and bad years for sake rice. Then, it waxes technical. It explains in excruciating detail how higher averages temperatures lead to longer Amylopectin (one of the two components of starch) chains. This means that the starches will dissolve very easily in the moromi (fermenting mash), which means more flavorful sake if controlled, but big-assed sloppy flavors if not reined in. It also accordingly means that resulting sake will be more susceptible to aging the adverse effects of aging.

Then, it waxes technical. It explains in excruciating detail how higher averages temperatures lead to longer Amylopectin (one of the two components of starch) chains. This means that the starches will dissolve very easily in the moromi (fermenting mash), which means more flavorful sake if controlled, but big-assed sloppy flavors if not reined in. It also accordingly means that resulting sake will be more susceptible to aging the adverse effects of aging. Summer in Japan this year was again hot, just about as hot as last year was. The warmer temperatures of the past decade and then some have continued. Furthermore, the islands of Japan were pummeled with typhoons this fall, meaning lots and lots of rain. Factoring in all that and more, the prognosis was that this year’s rice will be not dissolve very well; not too bad, mind you. Just not so well.

Summer in Japan this year was again hot, just about as hot as last year was. The warmer temperatures of the past decade and then some have continued. Furthermore, the islands of Japan were pummeled with typhoons this fall, meaning lots and lots of rain. Factoring in all that and more, the prognosis was that this year’s rice will be not dissolve very well; not too bad, mind you. Just not so well. That’s the cool thing about sake: in making it, we can meet nature half-way. What will most noticeably suffer are the highest grades of sake, contest sake especially. But for most of us, what we will be drinking will be as good as it usually is; but we should not forget that added burden that will be on rice farmers and brewers to make it that way. Sake, like wine, remains an integral expression of nature.

That’s the cool thing about sake: in making it, we can meet nature half-way. What will most noticeably suffer are the highest grades of sake, contest sake especially. But for most of us, what we will be drinking will be as good as it usually is; but we should not forget that added burden that will be on rice farmers and brewers to make it that way. Sake, like wine, remains an integral expression of nature.