Readers are likely aware that I publish another newsletter, Sake Industry News, thanks to the liberal use of ads in this publication. In every other issue of SIN, we publish an interview with a brewer that consists of ten questions about the brewing season. Last issue, we published such an interview with a brewer that was chock full of interesting insights. (To find out who, please subscribe to Sake Industry News! You’ll be glad you did!)

Readers are likely aware that I publish another newsletter, Sake Industry News, thanks to the liberal use of ads in this publication. In every other issue of SIN, we publish an interview with a brewer that consists of ten questions about the brewing season. Last issue, we published such an interview with a brewer that was chock full of interesting insights. (To find out who, please subscribe to Sake Industry News! You’ll be glad you did!)

One of the questions we asked him was, “How was production volume this year compared to last year? Up, down or the same?” His answer was that it was about the same. However, he went on to say that due to COVID19, sales have slumped significantly.

“We may have to reduce volume over the next few years. We’ve already committed to our rice purchase for next year so we won’t be able to adjust until the year after. It’s really quite scary!” he continued.

Just how challenging this can be for sake brewers – and rice growers too – might not be evident to most people, so let’s look at it here.

Naturally, all sake brewers want stable businesses, and most want to grow their business as well. And naturally enough they need to balance supply and demand. If they run out of product, consumers will run to other producers. But if they make too much sake, more than can be reasonably sold, it runs the risk of getting old and suffering in quality. In truth, there a dozen ways to mitigate the problem of having too much sake on hand, but not letting the problem arise in the first place is better than any of them.

So balancing what they think they can sell with how much they produce is a big part of running a sake-brewing business. There is much to take into account: trends, plans, stock on hand, economic environments and more will all affect sales. But after assessing what they think they can sell and how much they need to brew, they order rice.

Bear in mind with very, very few exceptions sake brewers do not own rice fields or grow their own rice. And even among those that do, no brewer grows all the rice needed for a full year’s production. Instead, they order it from farmers, usually through agricultural cooperatives but sometimes by direct contract.

Rice-growing is a whole ‘nother industry in Japan, with its own challenges. Naturally, farmers want to grow as much as they are legally permitted, but also need to be able to sell that rice easily. And like sake brewing, that calls for a whole lot of planning. Rice is harvested in the fall, but planting begins in the spring, somewhere between March and June. Planning just what rice will be grown where, and, for many farmers, how much will be sake rice and how much eating rice or even rice for some other use must all be planned way in advance.

Rice-growing is a whole ‘nother industry in Japan, with its own challenges. Naturally, farmers want to grow as much as they are legally permitted, but also need to be able to sell that rice easily. And like sake brewing, that calls for a whole lot of planning. Rice is harvested in the fall, but planting begins in the spring, somewhere between March and June. Planning just what rice will be grown where, and, for many farmers, how much will be sake rice and how much eating rice or even rice for some other use must all be planned way in advance.

What that means is that sake breweries place rice orders in February or so for rice for the following fall. Remember, every year is different. It might be a bumper crop, but yields might be much lower than usual. And much can change between the time rice is ordered and the time it hits the market a year later. Lots of things might change. Like COVID, for example.

And that is what happened this year. Brewers looked at things like sales trends up until February, and made decisions on how much sake rice to order. But due to COVID, overall sake sales in March dropped about 13 percent, and some individual brewers saw drops of 40 and 50 percent of shipments in March and April. Naturally, this would drastically drop the amount of rice one would normally order, but the orders were already in.

Modifying those orders is not a simple thing. In fact, sometimes it is just not possible. So much goes into the planning of how much rice and which rice will be grown where that it simply cannot be changed quickly. If a field in which sake rice was grown all of a sudden is used for another agricultural product, it is very difficult to change it back to sake rice. It just doesn’t work that way.

Modifying those orders is not a simple thing. In fact, sometimes it is just not possible. So much goes into the planning of how much rice and which rice will be grown where that it simply cannot be changed quickly. If a field in which sake rice was grown all of a sudden is used for another agricultural product, it is very difficult to change it back to sake rice. It just doesn’t work that way.

Some might think that another solution would be, rather than ask a farmer to just grow another rice, instead just say, “cancel the order, and let the field be empty this year,” but apparently that is even worse.

So in many cases, the brewers will be stuck with the rice that was ordered, and that is why it is “quite scary” to our interviewed brewer.

In truth, there are a handful of potential solutions. The rice can be stored at cold temperatures and used later – but the energy costs are significant. The brewed sake can be made in such a way that it stands up to time in the bottle better, stored colder than normal to slow down maturation (at a cost, of course!) and sold later than originally planned. And then, if need be, the following year’s production can be planned around the surplus.

But the rice-growing industry might not be able to adapt as fast.

In truth, it is a fairly intricate problem involving several industries, and it also depends on the whims of nature and the economic environment. Just how it will pan out, of course, remains to be seen. Stay tuned!

So the problem is complicated. But the solution is the same: all of us need to drink more sake. If we can enjoy more sake and nudge demand up steadily in spite of all that is happening in these times, we are doing our part, and all that we can to help the sake industry.

And speaking of Sake Industry News, why not subscribe today! Learn how to do that below.

Also check out my Sake Education Video Channel on YouTube here:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Know more. Appreciate more.

Know more. Appreciate more.

Interested in learning more about sake, and the industry in Japan that makes it? Subscribe to Sake Industry News, a twice-monthly newsletter covering news from within the sake industry in Japan. Learn more and read a few sample issues here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

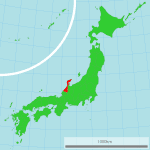

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today.

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today. eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate.

eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate. Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances.

he sake world is rife with paradox. There are so many aspects of sake that are this way, you are told, but a day later another authority says, no, it is not that way. And while you are still scratching your head to figure it all out, you discover things to support both sides of the story. And then, yet a completely different side appears too. Sure, there are principles and rules, but sometimes the exceptions to them outnumber the conforming instances. the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role?

the completed sake. This concept is backed up by the fact that a dozen brewers can take the same rice, even milled to the same degree, and make a dozen completely different sake. How then could the rice really play that much of a leading role? And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone.

And make no mistake: when top-grade rice like that is in the hands of a good toji and crew, the resulting sake is something special, something beyond the norm. It is not really a matter of being sweeter, or dryer, or more balanced or more expressive or fuller. It’s much harder to nail down concretely, but the difference seems to be a matter of reverberation or resonance in the overall flavor profile. But it is immediately recognizable as something that is clearly a but above. One great example of this is Isojiman Junmai Daiginjo made with Yamada Nishiki from Tojo in Hyogo, but there are others. And this makes it clear that the best rice can lead to subtle qualities that appeal to almost everyone. company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy.

company), and we were discussing their labeling as we did so. They do not hide the grade of each of their products, but do not put it on the front label either, relegating it to small characters on the back label. But each product has a unique name, like a sub-brand, that lets consumers associate an impression with it. So selecting and remembering their products are quite easy. While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

While the reasons and reality of that approach could go on forever, one things struck as quite significant. Their products are extremely enjoyable, and also extremely consistent. The toji has it dialed in: he knows just what to do with whatever rice he can get to make the final product taste just like that made with Yamada Nishiki. I am willing to bet he struggles more with the non-Yamada to get it to “behave” than he would like. But at the end of the day, he maintains great quality and stability while using “mostly Yamada, but not always.”

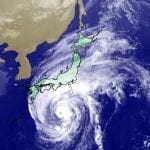

The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider.

The weather has been warmer the past few decades, and the environment has been much less stable overall. Japan is experiencing this as much as anywhere else, and while its effect on the sake world is not yet huge, everyone is aware of the changes and how they could impact things in the future. Sake production itself and, of course, rice growing are the two main things to consider. But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries.

But today, temperature control is much easier than in the past. Tanks can be concentrated into smaller space than in the past, and those rooms within the kura can be further insulated and cooled with modern climate control equipment, no problem. Individual tanks themselves can be chilled too, with all kind of tools now available such as jackets through which coolant can be run. Jury-rigged versions like garden hoses running chilled water can also be used for more budget-conscious breweries. Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

Because he has his eye on the future. He feels that in time, good sake rice production may move further north. So he wants to get experience with the rice from that region and learn to make increasingly better sake with it. And, furthermore, he wants to open the channel of distribution and establish a relationship with the rice-producing industry up there, so that when Hokkaido rice gets more attention, he will enjoy the benefits of having developed a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship that will afford him preferential status.

The brewing season – the first one of the new Reiwa era in Japan – has just begun. Most places have a tank or two, maybe more, already fermenting away. The fall is also the season for lots of tasting events of all kinds of groups and of various scales.

The brewing season – the first one of the new Reiwa era in Japan – has just begun. Most places have a tank or two, maybe more, already fermenting away. The fall is also the season for lots of tasting events of all kinds of groups and of various scales. Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended.

Bottles are lined up on a long, narrow table approachable on both sides, and flanked with spittoons strategically placed every meter or so. Each sake is labeled with the batch number of from whence it came. The handout received upon entering gives us the necessary information: “Batch #37, Junmai-shu, Hitomebore rice at 60%, Miyagi Yeast, Nama Genshu, Nihonshudo 5, Acidity, 1.5.” And so on down the line. Furthermore, we were given the date on which the sake was pressed, i.e. the day fermentation ended. Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product.

Are there exceptions to this? Of course there are. There are exceptions to everything in the sake world. For example, there are some brewers that deliberately do not blend their products so as to let the uniqueness of each tank do the talking – the sake called Mana 1751 is one such example. And one large and historically very significant company, Kenbishi, does in fact identify three or more tanks in each year’s batch that will morph into something very special when blended. But most of the time, for almost all brewers, blending is done to promote uniformity across all the tanks destined to be sold as one particular product. When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed.

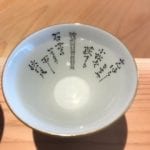

When looking at the history of sake, both culturally and from the point of technical developments, there is a period in the “dark ages” during which sake brewing was done mainly in shrines and temples in Japan. Interestingly, this was a period of huge strides in brewing methods and technology. But unfortunately, this period of sake history tends to get conveyed in a very abbreviated and minimalist form. It usually takes a back seat to issues such as knowing the grades and types, or how sake is brewed. characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods.

characterized by the veneration of spirits in nature and nature’s manifestations, as well as ancestors, and is refreshingly free of anything remotely resembling a formal dogma.) There is a Shinto ceremony called O-miki performed with a Shinto priest in a shrine, and using unique white porcelain flasks (called miki-dokkuri) and cups that can be seen on the altars of shrines everywhere. In this ceremony, a small amount of sake is drunk in a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods. And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice.

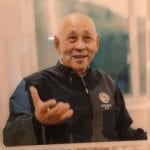

And so it was here that brewing methods were developed that led to much better sake, a definition that includes (as well it should) significantly higher alcohol levels. Most significantly, it was about this time when the rice, koji and water were added to the fermenting mash in two separate doses to help keep the yeast population at levels high enough to defeat bacterial intruders through sheer numbers. (This later evolved into three additions, as it remains today.) A form of yeast starter known as “Bodai-moto” was also developed by these clever clerics, and this is considered to be the roots of the kimoto yeast starter method, widely recognized as the original yeast starter method of modern sake brewing. Other significant technical developments from the Nara Buddhist temples include pasteurization and milling both the koji rice and the regular rice. Like all worlds, the sake world has its luminaries, its celebrities, and its legendary figures. It would stand to reason that such personages are usually the creators of sake with great reputations; in other words, we would naturally expect that most sake celebrities would be toji, the master brewers behind great brands of sake. However, quite paradoxically, oftentimes the very people that would qualify for such reputations are too humble to claim them. But there have been a few whose presence and reputation loom so large that they end up becoming reluctant legends.

Like all worlds, the sake world has its luminaries, its celebrities, and its legendary figures. It would stand to reason that such personages are usually the creators of sake with great reputations; in other words, we would naturally expect that most sake celebrities would be toji, the master brewers behind great brands of sake. However, quite paradoxically, oftentimes the very people that would qualify for such reputations are too humble to claim them. But there have been a few whose presence and reputation loom so large that they end up becoming reluctant legends. “retirement” to work at nearby Kano Shuzo making the well-known sake Jokigen. This he did for 14 years, until 2012. Do that math: he retired the second time at 79.

“retirement” to work at nearby Kano Shuzo making the well-known sake Jokigen. This he did for 14 years, until 2012. Do that math: he retired the second time at 79. But there he was: quick, dexterous and strong. Together with the young’uns, he was hauling just-steamed rice bundled in cloth, moving with speed and purpose. Later, he was in the koji-making rooms, which are kept between 35C and 45C (!) and at highly humid conditions, working on breaking up rice clumps and spreading and mixing koji mold. It is hard for a normal human being to just be in such an environment, and much harder to actually move and work in one. But there he was, looking as natural and at-home as he could be, exuding the comfort of one who knows just where he truly wants to be.

But there he was: quick, dexterous and strong. Together with the young’uns, he was hauling just-steamed rice bundled in cloth, moving with speed and purpose. Later, he was in the koji-making rooms, which are kept between 35C and 45C (!) and at highly humid conditions, working on breaking up rice clumps and spreading and mixing koji mold. It is hard for a normal human being to just be in such an environment, and much harder to actually move and work in one. But there he was, looking as natural and at-home as he could be, exuding the comfort of one who knows just where he truly wants to be. the nickname “demon.” In fact, his 2003 autobiography was entitled “Demon’s Sake.” So I might not be quite so gushing had I actually had that experience. Still, I am sure the level of respect would be just as high, albeit laced with a few more emotions. But what do I know?

the nickname “demon.” In fact, his 2003 autobiography was entitled “Demon’s Sake.” So I might not be quite so gushing had I actually had that experience. Still, I am sure the level of respect would be just as high, albeit laced with a few more emotions. But what do I know? Mr. Noguchi is not the only great toji out there, nor is he the only famous toji. Far from it! The sake world has its own celebrities, more understated then their western counterparts though they may be. But their presence and aura invigorates the sake world, and makes it all that more interesting for all of us.

Mr. Noguchi is not the only great toji out there, nor is he the only famous toji. Far from it! The sake world has its own celebrities, more understated then their western counterparts though they may be. But their presence and aura invigorates the sake world, and makes it all that more interesting for all of us.