What else makes your sake taste and smell as it does?

In a previous post, we began talking about the “flavor elements of sake,” i.e. what things – ingredients, methods and “after-care” – combine in various ways to make the sake before you taste and smell the way it does. And last month we looked at the main ingredients and their contributions. Rice, water, yeast and koji all play their roles, and those roles are intertwined. If you missed that, you can check it out here.

In a previous post, we began talking about the “flavor elements of sake,” i.e. what things – ingredients, methods and “after-care” – combine in various ways to make the sake before you taste and smell the way it does. And last month we looked at the main ingredients and their contributions. Rice, water, yeast and koji all play their roles, and those roles are intertwined. If you missed that, you can check it out here.

This time around, let us consider the following brewing processes, the choice of which will alter the path a sake-in-waiting will tread. While there is potentially no end to the points would could consider, let us narrow it down to six: milling, yeast starter, pressing, pasteurization, whether or not added alcohol has been used, and aging.

And just like the ingredients side of things, none of these six processes have an absolutely guaranteed air-tight cause and effect relationship with the final sake. All are intertwined with the many other choices involved. But there are tendencies for sake made with these methods to end up tasting and smelling a certain way. So let us look at those admittedly tenuous-yet-valid connections.

Milling

Milling

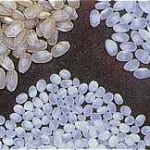

More than anything else, milling affects lightness: the more the rice is milled before brewing begins, the lighter and more refined the sake will be. But milling affects more than just the lightness as well – more highly milled rice can indirectly lead to more fruity aromas. And other things affect lightness or heaviness as well. But in general, the more you mill the rice, the lighter and more refined the sake will be.

This is because milling the rice more takes away increasingly more of the fat and protein lurking near the surface that lead to richer, fuller flavors.

Note that more milling is not always better, even though that point is used often in product marketing. Lighter sake is not unequivocally better than richer sake; not at all. And more milling does not guarantee a lighter sake. But the tendency is in fact there.

Yeast Starter

More than anything else, the choice of yeast starter affects flavor elements like sweetness, acidity and umami, expressed perhaps as “clean-ness versus richness.”

This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that.

This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that.

What are those three main methods? Wincing at how inappropriate it is to constrain them to a single paragraph, they are: sokujo, kimoto and yamahai. Sokuju the most modern (yet still over a hundred years old), used to make 99 percent of all sake out there, and leads to clean sake.

Kimoto is the oldest and most traditional, very little is made, and leads to richer sake, often with a bright (almost tart) acidity and fine-grained flavor.

Yamahai is also about 100 years old and often yields richer, wilder sake with higher sweetness and acidity.

However, the above three descriptions are just tendencies, albeit solid ones to be sure. But not all yamahai is wild, not all kimoto is fine-grained, and not all sokujo is squeaky clean.

Note these three methods are also affected by everything else: milling, rice, yeast, water and more. The choice of yeast starter alone does not guarantee anything.

And the method chosen affects other things than the over-simplistic flavor profiles described above. But in short, the choice of yeast starter method affects clean-ness versus richness.

Pressing Method

More than anything else, the choice of pressing method affects expressiveness and intensity.

After a month-long fermentation period, the mash is pressed through a mesh, removing the remaining rice solids and sending the completed sake through. Not surprisingly there are a few main methods in use for this pressing step, and just as unsurprisingly they lead to different type of sake.

Machine press

Machine press

Most sake is pressed using a machine that does this very efficiently. The fermented mash is forced through mesh panels leaving the dregs clinging to the mesh and the golden ambrosia comes out the other end. This machine does a great job and saves untold amounts of labor.

Fune (box press)

Fune (box press)

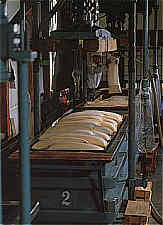

However, a brewer can perform this step in other ways too. One such method involves pouring several liters of the fermented mash into a meter-long cloth bag, and then piling those bags into a large, sturdy box maybe two-across, twenty-long, and ten-high – or thereabouts. The lid is then cranked down and into the box, and the sake comes out a hole in the bottom. Sake pressed in this method is usually called funa-shibori and is often more pronounced, expressive and aromatic.

Shizuku

Shizuku

For those brewers and sake for which this is just not going far enough, the same bags o’ mash can be tied off and hung, and not squeezed at all. This drip-pressing method is called shizuku, And the sake that drips out is even more extravagantly aromatic, expressive and definitely intense.

However, many other things affect the expressiveness and intensity of a sake; the pressing method is just one of ‘em.

So in short, machine press – just fine; funashibori (box press) – more lively and aromatic; shizuku (drip press) – even more intense and expressive.

Pasteurization

Pasteurization

Most sake is pasteurized by heating it to about 60C or so for a short time. This stabilizes the product by killing off lactic bacteria and stifling enzymes that would otherwise feed those bacteria. When sake is not pasteurized it is called nama-zake, and is a very different animal.

Nama-zake can be livelier and more vibrant, often with more pronounced characteristic aromas. These aromas may be woody at first, and cheesy if the sake is not kept cold and away from oxygen.

While many find properly cared for nama to be more appealing, it is not unequivocally better – just different. Furthermore, nama-zake will mature much more quickly than pasteurized sake.

So, in short, nama is usually livelier in aromas, and pasteurized sake more settled and deep. But of course, there are exceptions.

Junmai vs. Jon-Junmai

Junmai means the sake was made with rice, water and koji only. If the junmai word is not on the bottle, then a bit of distilled alcohol has been added just after fermentation and before pressing to help extract more flavor and aroma, lighten the sake a bit, and improve shelf life as well. (Admittedly, in cheap sake lots is added to stretch yields, but in premium stuff this is neither the goal nor the result.)

Junmai types are often richer and fuller, especially compared to their non-junmai counterparts. So junmai ginjo is richer than (added-alcohol) ginjo, and junmai daiginjo is richer than (added-alcohol) daiginjo. Unless it isn’t.

Sometimes, that is simply not the case, and many people cannot tell the difference in most situations.

Ergo, in a nutshell, junmai types are slightly richer than added alcohol types. Usually.

Aging

Aging

This is the simplest of the method-related generalizations here: aged sake takes on color, a sherry-like quality, earthiness and more pronounced flavors. Many factors affect this: the milling of the original sake, whether it is junmai or added-alcohol, time, temperature and vessel.

But in its simplest form, the more mature a sake is, the more intense and sherry-like its flavors and aromas become – most of the time, that is.

Most sake is shipped and meant to be consumed young: within a year or two. Very, very little is aged for more than a couple of years. While that rabbit hole, too, is deep, fascinating and enjoyable, it is a very small part of the market for now.

Along with last month’s assessment of the main ingredients of sake, the above runs down a few of the many options a brewer has in making sake, and how those choice will more than likely – but not absolutely – affect the fine nature of the sake. A quick review of the last line in each section should suffice as a quick-n-simple assessment of how each step affects the final product, and should hopefully be useful in knowing why your sake tastes the way it does, or what to expect based on the info on the label.

But superseding this all is the warm-n-fuzzy elusive nature of sake. As soon as we think we got it figured out, it hoses our hubris. And therein lies the fun.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more here.

Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more here.

Sake is booming; it is growing strongly in popularity both inside Japan and around the world. And while this is true, we still have a long way to go. In an effort to curb I.S.E. (irrational sake exuberance), here are some sobering statistics that will encourage us to drink more sake and to promote it actively.

Sake is booming; it is growing strongly in popularity both inside Japan and around the world. And while this is true, we still have a long way to go. In an effort to curb I.S.E. (irrational sake exuberance), here are some sobering statistics that will encourage us to drink more sake and to promote it actively. Only 3.2 percent of all sake made is exported

Only 3.2 percent of all sake made is exported Sixty percent of all sake breweries are small to mid-sized companies, of which half are either losing money or barely (i.e. insignificantly) profitable.

Sixty percent of all sake breweries are small to mid-sized companies, of which half are either losing money or barely (i.e. insignificantly) profitable. A quarter of a million tons. The fact that only thirty six percent was proper sake rice is not disconcerting at all, since so much non premium sake is made – it is still 65 percent of the market. So the numbers are just about right, even if a bit inconceivably large in scale.

A quarter of a million tons. The fact that only thirty six percent was proper sake rice is not disconcerting at all, since so much non premium sake is made – it is still 65 percent of the market. So the numbers are just about right, even if a bit inconceivably large in scale.

The government in Japan, in particular the National Tax Administration, monitors trends in sake preferences amongst consumers, as expressed by trends in sake production. The results of the analysis of data from last year’s sake was released a short while ago. While it is nothing shocking, it is interesting to see how things change. Here are a couple of tendencies culled from that slurry of data.

The government in Japan, in particular the National Tax Administration, monitors trends in sake preferences amongst consumers, as expressed by trends in sake production. The results of the analysis of data from last year’s sake was released a short while ago. While it is nothing shocking, it is interesting to see how things change. Here are a couple of tendencies culled from that slurry of data. Again, hardly surprising, but the level of the ester ethyl caproate, which leads to aromas like ripe apple, tropical fruit and licorice or anise, has been on the increase. Curse it. This is hardly surprising considering that ginjo and daiginjo continue to grow very strongly in popularity.

Again, hardly surprising, but the level of the ester ethyl caproate, which leads to aromas like ripe apple, tropical fruit and licorice or anise, has been on the increase. Curse it. This is hardly surprising considering that ginjo and daiginjo continue to grow very strongly in popularity. Non-premium sake has seen a decrease in alcohol content overall. Ginjo et cetera has seen alcohol levels stay fairly high, likely for increased impact, but in non-premium futsuu-shu alcohol has dropped a bit on the average. I am not sure what the significance of this point is, though, nor was it elucidated upon in the government report.

Non-premium sake has seen a decrease in alcohol content overall. Ginjo et cetera has seen alcohol levels stay fairly high, likely for increased impact, but in non-premium futsuu-shu alcohol has dropped a bit on the average. I am not sure what the significance of this point is, though, nor was it elucidated upon in the government report. In a previous post, we began talking about the “flavor elements of sake,” i.e. what things – ingredients, methods and “after-care” – combine in various ways to make the sake before you taste and smell the way it does. And last month we looked at the main ingredients and their contributions. Rice, water, yeast and koji all play their roles, and those roles are intertwined. If you missed that, you can check it out

In a previous post, we began talking about the “flavor elements of sake,” i.e. what things – ingredients, methods and “after-care” – combine in various ways to make the sake before you taste and smell the way it does. And last month we looked at the main ingredients and their contributions. Rice, water, yeast and koji all play their roles, and those roles are intertwined. If you missed that, you can check it out  Milling

Milling This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that.

This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that. Machine press

Machine press Fune (box press)

Fune (box press) Shizuku

Shizuku Pasteurization

Pasteurization Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more

Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more  What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty.

What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty. (Actually, since those are the extent of sake’s ingredients, that ain’t really narrowing it down, but you know…) And let us consider the following steps as the brewing methods that affect the nature of the sake: milling, yeast starter methods, pressing methods, pasteurization, whether or not alcohol has been added (i.e. whether or not it is a junmai style) and aging.

(Actually, since those are the extent of sake’s ingredients, that ain’t really narrowing it down, but you know…) And let us consider the following steps as the brewing methods that affect the nature of the sake: milling, yeast starter methods, pressing methods, pasteurization, whether or not alcohol has been added (i.e. whether or not it is a junmai style) and aging. I. Rice = Flavor

I. Rice = Flavor Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

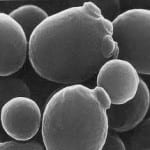

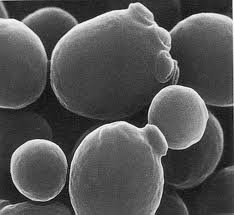

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake. industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter. shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.” Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.

Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.