What is Shochu?

Shochu is Japan’s other indigenous alcoholic beverage, but unlike sake, shochu is distilled. It is also made from one of several raw materials. The alcoholic content is usually 25%, although sometimes it can be as high as 42% or more.

The word “sake” in Japan can actually refer to all alcoholic beverages in general, although it most often refers to the wine-like rice brew so tightly associated with that word overseas. But in some parts of Japan, most notably the far western and southern regions, the word sake is understood to refer to a totally different alcoholic beverage, also indigenous to Japan, but distilled and not brewed: shochu.

Like almost all such beverages throughout the world, shochu developed as it did as an expression of region, especially climate, cuisine and available raw materials. Perhaps the factor most affecting the development of shochu is the weather. The island of Kyushu and the western part of the island of Honshu are significantly warmer than the rest of Japan.

Brewing sake calls for relatively lower temperatures, but shochu can be distilled in these warmer regions. Also, the higher alcohol content and drier feel is more appealing to many in milder climates.

Unlike many other beverages, shochu is made from one of several raw materials. These include sweet potato, and shochu made from these is called “imo-jochu.” Other materials commonly used include from rice, soba (buckwheat), and barley. There is even one island where there a few places that make shochu from brown sugar. It can also be made from more obscure things like chestnuts and other grains.

And, each of these raw materials gives a very, very distinct flavor and aroma profile to the final sake. These profiles run the gamut from smooth and light (rice) to peaty, earthy and strong (potato). Indeed, each of these raw materials lends a unique flavor in much the same way that the peat and barley of each region in Scotland determine the character of the final scotch whiskey.

There are, in fact, many parallels between shochu and scotch, regional distinction based on local ingredients being only one of them.

Another parallel to scotch can be found in the distillation methods. There are basically two main methods of distillation. The older method – it has been around since the 14th century or so – involves a single round of distillation only, and is made using only one raw material. Known as Otsu-rui (Type B – in an admittedly loose translation) or Honkaku (“the real thing”) shochu, this type will more often reflect the idiosyncrasies of the original raw material. In this sense, it can be likened to single malt scotches.

The second method is one in which the shochu is goes through several distillations, one right after another. It is often made with several of the commonly used raw materials. Known as Kou-rui (Type A, in the same admittedly loose translation) shochu, this method has only been around since 1911, although it only became a legal classification in 1949. With a bit of a stretch, this kind of shochu is similar to much blended scotch. In other words, it is much smoother, ideal for mixing in cocktails, and with much less … well, character.

Beyond these variables, the type of koji mold (used to create sugar from the starch of the raw materials during the fermentation step that necessarily takes place before distillation) can be one of three, (yellow koji, as is used with sake, white koji and black koji) and the distillation itself can take place at either atmospheric pressure or at a forced lower pressure. These parameters too naturally affect the style of the final product.

Kou-rui shochu, of which much more is produced by far, is quite versatile. As it is lighter and cleaner, it lends itself well to use in mixed drinks. Perhaps its most ubiquitous manifestation is the popular “chu-hi,” a shochu hi-ball made using a plethora of different fruit flavors and sold in single-serving cans or mixed fresh at bars and pubs. (Since it is supposedly cleaner by virtue of having been repeatedly distilled, it is said by some to give less of a hangover, although there is no evidence to truly back this up.)

Otsu-rui shochu, the “real thing” honkaku-shochu, on the other hand, has a more artisan, hand crafted appeal associated with it. The nature of the raw material can really come through, and be it soba, rice, barley, or chestnuts, each has its fans and foes. This is especially true when it has been distilled at atmospheric pressure, not forced lower pressure.

Perhaps the most interesting – and illustrious – of all shochu are those made from the sweet potatoes of Kagoshima Prefecture: imo-jochu. While the flavors can be heavier and more earthy than shochu made from other starches, Kagoshima imo-jochu offers complexity and fullness of flavor that makes it quite enjoyable to many a connoisseur.

Honkaku “the real thing” shochu is usually enjoyed straight, on the rocks, or with a splash of water. Another way to enjoy either type of shochu is known as “oyu-wari,” which is simply mixing it with a bit of hot water. This both backs the alcohol off a bit, releases flavor and aroma, and warms the body to the very core. Unbeatable in winter, for sure. From experience, I can guarantee it will warm you from the core outward.

Shochu overall is enjoying massive popularity these days in Japan. Over the last couple of years, both beer and sake consumption have continued to drop, where as shochu has actually increased.

While shochu has its roots in either China or Korea, probably having come across during trading, the traditional home of shochu in Japan is Kagoshima, on the island of Kyushu. In fact, the first usage of the term shochu appeared in graffiti written by a carpenter dated 1559 in a shrine in the city of Oguchi in Kagoshima.

Kagoshima is rightfully proud of their shochu heritage. It is the only prefecture in Japan that brews absolutely no sake, but only produces shochu. If you ask for sake down there, expect and enjoy the local sweet-potato distillate.

The difference between soju and shochu

Korea also makes shochu, although it is called soju in Korean. And, Korean producers got to the US with it first. As such, in US legalese, the product is known as shochu. As far as I know, all Japanese shochu will be legally referred to as soju in the US. It is, in essence, the same thing. Judge it on its flavor, not its label.

What is Awamori?

Awamori is an alcoholic beverage indigenous to and unique to Okinawa. made from rice, however, it is distilled from rice, not brewed. The traditions and methods of Awamori originally came in from Thailand (although with influences from the south, from Indonesia and Taiwan, and from the north, from China and Korea it is said), and awamori was actually the very first distilled beverage in what is now Japan.

Awamori is made only in Japan’s southern most prefecture, the tropical island group of Okinawa. Currently, there are but 47 makers of this unique, earthy beverage, although awamori is enjoying a boom right now, and business is brisk. Due to the influence of the US presence from WWII until 1972, for decades the drink of choice in Okinawa was scotch or whiskey. Now, however, this erstwhile gift to the Shogun of Japan has resumed its rightful place as a very popular sipping beverage in its own land.

There are quite a few ways in which awamori is unique. The pre-distillation ferment is made in such away that there is plenty of citric acid created, which allows awamori to be made all year round in this hot climat. It is distilled once, and afterwards the alcohol content is lowered with water to about 25 to 30 percent, although some awamori is found at 43 percent alcohol.

There are several theories on the origins of the word awamori itself. “Awa” means foam and “mori” can mean to rise up. One theory then is that the foam would rise in great swaths during per-distillation fermentation. Another is that long ago the level of alcohol was measured by pouring the awamori from a height of an outstretched arm into a small cup, and measuring how much foam rose in the cup. Yet a third, less romantic, states that this name was forced upon the Ryukyu distillers by the Satsuma clan of Kagoshima to be sure that it would not be confused with their beloved shochu.

Etymological considerations aside, as mentioned above, awamori is a beverage distilled from rice. It differs from sake, mainland Japan’s indigenous drink, in that sake is brewed, not distilled. Also, sake is made with short-grain Japonica rice, whereas awamori is made using long-grain indica rice that is imported from Thailand (even today). It differs from shochu, Japan’s other distilled beverage, (although much shochu is made from materials other than rice) in several ways, including process variations, as well as the type of koji mold (used for saccharification) and yeast.

A word worth remembering when shopping for awamori is “kusu.” Kusu is aged awamori. It is written with the same characters as the Japanese word koshu, which refers to aged sake, the pronunciation is unique to Awamori and Okinawa.

Awamori was meant to be aged, and aged for a long time. Like many beverages distilled from grains, aging mellows the flavor and rounds out the edges. While awamori aged ten years can be wonderful, it becomes even more enjoyable at 20 or 25 years. (One of the challenges to the awamori industry is how to remain financially viable while they wait on the returns of their long-term investment.)

But the traditional method of aging awamori, known as “shitsugi,” is very curious and does not boast a high degree of repeatability. To explain it, we need to bear in mind that hundreds of years ago, when the Ryukyu kingdom was in its heyday, folks would have several lidded urns of awamori lined up outside the house. The urn containing the oldest awamori was closest to the door, with each urn having successively younger product inside.

When a drink was ladled out from the first urn, the amount taken was then replaced with awamori from the second urn. This in turn was refilled from the third urn and so on. Freshly distilled stuff was placed into the last urn when ready. This led to each urn having inside of it an indeterminable blend of awamori of different degrees of aging. So although kusu refers to aged awamori, traditionally it was not really possible to be any more precise than that.

Modern times, laws, and consumer guidelines call for a bit more accuracy, and currently for a bottle of awamori to have kusu on the label, at least 51% of the contents must have been aged at least three years. While this allows for the traditional shitsugi method of aging, it still means that 49% of it could be freshly distilled stuff. So, while it may be a bit harder to find and a tad more expensive, it is worth it to search for 100% kusu of ten years or more. It will be clearly written as such on the bottle, i.e. “100% aged 10 years,” or something to that effect. Having said that, it is very difficult to find something like a bottle of kusu of which 100% has been aged 25 years.

When the Ryukyu kingdom was in its prime, the best kusu was served at only the most special of occasions. It was presented in very small thimble-sized cups, called “saka-jiki ,” holding perhaps a tablespoon, that are dwarfed by the average “o-chokko” sake cup. These ae still used today in some situations. It was said that while wealthy people might entrust their money to others, they would always keep the keys to their awamori cellar with them.

SAKE CONFIDENTAL

SAKE CONFIDENTAL

Interested in learning more about sake?

Check out my book “Sake Confidential” on Amazon.

Sake Confidential is the perfect FAQ for beginners, experts, and sommeliers.

Indexed for easy reference with suggested brands and label photos. Includes:

- Sake Secrets: junmai vs. non-junmai, namazake, aging, dry vs. sweet, ginjo, warm vs. chilled, nigori, water, yeast, rice, regionality

- How the Industry Really Works: pricing, contests, distribution, glassware, milling, food pairing

- The Brewer’s Art Revealed: koji-making, brewers’ guilds, grading

SAKE INDUSTRY NEWS

If you are interested in staying up to date with what is happening within the Sake Industry and also information on more advanced Sake topics then Sake Industry News is just for you!

Sake Industry News is a paid subscription newsletter that is sent on the first and 15th of each month. Get news from the sake industry in Japan – including trends, business news, changes and developments, and technical information on sake types and production methods that are well beyond the basics – sent right to your inbox. Subscribe here today!

Each issue will consist of four or five short stories culled from public news sources about the sake industry in Japan, as well as one or more slightly longer stories and observations by myself on trends, new developments, or changes within the sake industry in Japan.

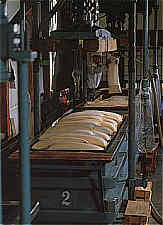

In last month’s newsletter, we spoke of the middle part of the pressing, and its numerous names. In other words, when the rice solids that remain after fermentation are filtered away, via a press of one sort of another, the terms nakagumi, nakadare and nakadori all mean the same thing, and all refer to the middle part, which is what comes out after the rough first part but before the start of the tired final bits. In other words, the middle part is the best.

In last month’s newsletter, we spoke of the middle part of the pressing, and its numerous names. In other words, when the rice solids that remain after fermentation are filtered away, via a press of one sort of another, the terms nakagumi, nakadare and nakadori all mean the same thing, and all refer to the middle part, which is what comes out after the rough first part but before the start of the tired final bits. In other words, the middle part is the best. that bottle went directly there. This differs from the norm in that most sake is first sent to a big tank where it all sits for a spell. Further sediment will settle, and the sake in that one tank is all thereby guaranteed to be uniform in taste and aroma.

that bottle went directly there. This differs from the norm in that most sake is first sent to a big tank where it all sits for a spell. Further sediment will settle, and the sake in that one tank is all thereby guaranteed to be uniform in taste and aroma. Throw all that together and in a sake labelled jikagumi, we can count on having an unfiltered, undiluted sake that has not been blended with any other bottle or batch. This makes it appealing in that each bottle is unique in our time-space continuum, in our universe, and in our reality. Wow.

Throw all that together and in a sake labelled jikagumi, we can count on having an unfiltered, undiluted sake that has not been blended with any other bottle or batch. This makes it appealing in that each bottle is unique in our time-space continuum, in our universe, and in our reality. Wow. press. We are talking like 2500 bottles for an average sized tank of premium sake, one after another. One. After. Another. Sure, the whole batch need not be done that way, and only a few bottles could be labelled as such. But still: it’s “hassle city.”

press. We are talking like 2500 bottles for an average sized tank of premium sake, one after another. One. After. Another. Sure, the whole batch need not be done that way, and only a few bottles could be labelled as such. But still: it’s “hassle city.” jikagumi is written on the label does not legally mean that anything had to happen or not happen. Trust that no one is trying to fool us here, but rather that some leeway of execution exists.

jikagumi is written on the label does not legally mean that anything had to happen or not happen. Trust that no one is trying to fool us here, but rather that some leeway of execution exists. The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com.

The next Sake Professional Course in which there are openings will be held in Miami Beach Florida, August 17~19. For more information and/or to make a reservation, please email me sakeguy@gol.com.

The region from which a sake comes is indirectly connected to the type of rice, since just like grapes and wine, different rice strains grow better in certain regions. Small as Japan is, there are many distinctly different climates, and different things grow in each.

The region from which a sake comes is indirectly connected to the type of rice, since just like grapes and wine, different rice strains grow better in certain regions. Small as Japan is, there are many distinctly different climates, and different things grow in each.