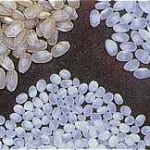

The main raw materials of sake are rice and water, and rice is the only fermentable material used in its production. And just as the grapes used to make good wine are significantly different from those bought at the supermarket, the rice used to make premium sake is significantly different from that which we find sitting under the fish in sushi, or in bowls in meals.

The main raw materials of sake are rice and water, and rice is the only fermentable material used in its production. And just as the grapes used to make good wine are significantly different from those bought at the supermarket, the rice used to make premium sake is significantly different from that which we find sitting under the fish in sushi, or in bowls in meals.

In truth, most sake – perhaps 75 percent of all produced – is actually made from regular table rice. And a lot of this is perfectly tasty sake. But when we meander into the realm of premium sake, especially ginjo, almost always it is made with proper sake rice, which is significantly different from regular table rice.

While there are many ways that sake rice differs from other types (size of the stalk, size of the grains, more starch, less fat and protein), the most talked about of them is surely the presence of a shinpaku.

In proper sake rice, the higher-than-normal starch content is mostly concentrated in the center of the grains. Why is this so heart-warmingly special? Because we want to get at the starch, which will be converted to sugar and then into alcohol. But we don’t want the fat and protein, which would lead to off-flavors and contribute rough elements to the sake. So with the starch neatly concentrated in the center, all we need to do is to mill away more and more of the outside of the grain, and by doing that we remove the fat and protein and leave only the starchy goodies behind.

In proper sake rice, the higher-than-normal starch content is mostly concentrated in the center of the grains. Why is this so heart-warmingly special? Because we want to get at the starch, which will be converted to sugar and then into alcohol. But we don’t want the fat and protein, which would lead to off-flavors and contribute rough elements to the sake. So with the starch neatly concentrated in the center, all we need to do is to mill away more and more of the outside of the grain, and by doing that we remove the fat and protein and leave only the starchy goodies behind.

That packet of starch in the center is called the shinpaku. The word itself is written with the characters for “heart” and “white,” and not surprisingly, when one looks at sake rice, you can clearly see that the heart of the grain is an opaque white, with everything around that being somewhat translucent. In regular rice, however, the color is uniform throughout since the starch, fat and protein are more mixed up and uniformly distributed.

Why does sake rice have the starch in the center, and fat and protein around that? Part of it is just the nature of those strains. But it also has to do with climate and growing conditions. Regions with hot days and cold nights are best for sake rice production, as the cold nights coerce the plant to send the starch to the center of the grains. In “bad years” for rice, seasons being too hot or too cold, too wet or too dry, or when the night and day temperatures had less variance, fewer grains will have a decent shinpaku.

Why does sake rice have the starch in the center, and fat and protein around that? Part of it is just the nature of those strains. But it also has to do with climate and growing conditions. Regions with hot days and cold nights are best for sake rice production, as the cold nights coerce the plant to send the starch to the center of the grains. In “bad years” for rice, seasons being too hot or too cold, too wet or too dry, or when the night and day temperatures had less variance, fewer grains will have a decent shinpaku.

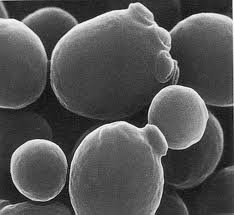

What is interesting is that it is not the starch itself that makes the center of the grains white. What happens is that the starch molecules are round at the ends, and as they rush to get to the middle they don’t interlock well, and they leave tiny air pockets between their ends. These diffuse light passing through, giving the opaque appearance we see.

Beyond different varieties or strains of rice, within each type there are grades based upon how well it was grown. This is a function of locale, climate, and skill of the producer. And one of the big points of assessment is the percentage of grains with a visible shinpaku. This is also one of the standards in the official assessment of sake rice versus table rice in general.

There are many more factors beyond the shinpaku and its size that are involved in qualifying good sake rice. But the shinpaku is the most visible, if not the most talked about.

Note, too, that one can make decent-to-good sake from regular rice. It takes a good toji and good tools, but just a few of the many examples of table rice from which decent sake is brewed are Koshihikari, Sasanishiki, the illustrious Kame no O. So one can indeed make decent sake from table rice. It’s just easier to do so with real sake rice.

Note, too, that one can make decent-to-good sake from regular rice. It takes a good toji and good tools, but just a few of the many examples of table rice from which decent sake is brewed are Koshihikari, Sasanishiki, the illustrious Kame no O. So one can indeed make decent sake from table rice. It’s just easier to do so with real sake rice.

Finally, the question often arises, if a brewer is using table rice, why do they bother to mill down to 70, 60 or even 50 percent of the original size? If table rice has no shinpaku, isn’t that meaningless and wasteful?

The answer lies in the fact that in truth, all rice to some degree has more starch in the center and more fat and protein near the surface, whether or not this is manifested in a visible shinpaku. It is just that this is all more distinct in sake rice; much more starch is in the center, and much more of the fat and protein is near the outside of the grains.

So more milling will have a positive effect on table rice as well when it is used in sake brewing, just not as pronounced as with good sake rice. As usual with sake-related things, it’s all a tad vague.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sake Professional Course

in Japan

Tuesday, January 10 ~ Saturday, January 14, 2017

Recognized by the Sake Education Council

No sake stone remains left unturned

“Quite simply, the best and most thorough sake education on the planet.”

From Tuesday, January 10 to Saturday, January 14, I will hold the 14th running (and 38th overall) of the Sake Professional Course in Japan.

The Sake Professional Course in Japan is far and away the best possible sake education in existence. Three days of lecture and tasting, each evening capped off with dinner and fine, fine sake, followed by two days spent visiting four sake breweries of different size and scale – punctuated again with fine sake and a great meal each evening make this course as comprehensive as it could be. If you are serious about sake, and especially about working with sake, there is no other course for you; this is it. Satisfaction is guaranteed.

The Sake Professional Course in Japan is far and away the best possible sake education in existence. Three days of lecture and tasting, each evening capped off with dinner and fine, fine sake, followed by two days spent visiting four sake breweries of different size and scale – punctuated again with fine sake and a great meal each evening make this course as comprehensive as it could be. If you are serious about sake, and especially about working with sake, there is no other course for you; this is it. Satisfaction is guaranteed.

The course is recognized by the not-for-profit organization The Sake Education Council, and those that complete it will be qualified to take the exam for Certified Sake Specialist, which will be offered near the end of the week.

The course will be held from the morning of Tuesday, January 10 to the evening of Saturday, January 14,2017, and will be focused in Tokyo, but with a two- day excursion to the Osaka – Kyoto – Kobe area to visit four sake breweries of various scale. Geared toward professionals, but open to anyone with an interest in sake, this course will begin with the basics, and will provide the environment for a focused, intense, and concerted training period. It will consist of classroom sessions on all things sake-related, followed by relevant tasting sessions, four sake brewery visits, and exposure to countless brands and styles in several settings, both in comparison to other sake, and with food. Participants will stay together at hotels in Tokyo and Osaka. Lectures will take place in a comfortable classroom, and evening meals will be off-site at various sake- related establishments.

The course will be held from the morning of Tuesday, January 10 to the evening of Saturday, January 14,2017, and will be focused in Tokyo, but with a two- day excursion to the Osaka – Kyoto – Kobe area to visit four sake breweries of various scale. Geared toward professionals, but open to anyone with an interest in sake, this course will begin with the basics, and will provide the environment for a focused, intense, and concerted training period. It will consist of classroom sessions on all things sake-related, followed by relevant tasting sessions, four sake brewery visits, and exposure to countless brands and styles in several settings, both in comparison to other sake, and with food. Participants will stay together at hotels in Tokyo and Osaka. Lectures will take place in a comfortable classroom, and evening meals will be off-site at various sake- related establishments.

The goal of this course is that “no sake stone remains left unturned,” and the motto is “exceed expectations.”

During the three classroom days, we will discuss various aspects of sake and the sake world, including grades, production, rice, yeast, koji, water and more. Tastings specific to the just-discussed topics follow each lecture, thereby allowing participants to understand with their senses the theory just presented. Participants will not simply hear about differences based on rice types or yeast types, they will taste and smell them. Students will not only absorb technical data about yamahai, kimoto, nama genshu, aged sake and regionality, they will absorb the pertinent flavors and aromas within the related sake as well.

Food and sake, the state of the sake-brewing industry, the culture and history suffusing sake are regionality are just a few more of the wide range of topics to be covered. Every conceivable sake-related topic will be touched upon, and each lecture will be complimented and augmented by a relevant tasting session.

Participants will also be presented with a certificate of completion at the end of the course.

The Tokyo classroom venue is the Japan Sake and Shochu Producers Association in the Shimbashi area.

The cost for this five-day educational experience is ¥190,000. This includes all instruction and materials, as well as evening meals with plenty of sake each night. Other meals, transportation to and from as well as within Japan, and hotel are not included in the tuition. To make a reservation or if you have any questions at all, please send an email to John Gauntner at sakeguy@gol.com .

The cost for this five-day educational experience is ¥190,000. This includes all instruction and materials, as well as evening meals with plenty of sake each night. Other meals, transportation to and from as well as within Japan, and hotel are not included in the tuition. To make a reservation or if you have any questions at all, please send an email to John Gauntner at sakeguy@gol.com .

For more information, a downloadable pdf announcement and a view of the daily syllabus, please go here . Testimonials from past participants can be found here as well.

The government in Japan, in particular the National Tax Administration, monitors trends in sake preferences amongst consumers, as expressed by trends in sake production. The results of the analysis of data from last year’s sake was released a short while ago. While it is nothing shocking, it is interesting to see how things change. Here are a couple of tendencies culled from that slurry of data.

The government in Japan, in particular the National Tax Administration, monitors trends in sake preferences amongst consumers, as expressed by trends in sake production. The results of the analysis of data from last year’s sake was released a short while ago. While it is nothing shocking, it is interesting to see how things change. Here are a couple of tendencies culled from that slurry of data. Again, hardly surprising, but the level of the ester ethyl caproate, which leads to aromas like ripe apple, tropical fruit and licorice or anise, has been on the increase. Curse it. This is hardly surprising considering that ginjo and daiginjo continue to grow very strongly in popularity.

Again, hardly surprising, but the level of the ester ethyl caproate, which leads to aromas like ripe apple, tropical fruit and licorice or anise, has been on the increase. Curse it. This is hardly surprising considering that ginjo and daiginjo continue to grow very strongly in popularity. Non-premium sake has seen a decrease in alcohol content overall. Ginjo et cetera has seen alcohol levels stay fairly high, likely for increased impact, but in non-premium futsuu-shu alcohol has dropped a bit on the average. I am not sure what the significance of this point is, though, nor was it elucidated upon in the government report.

Non-premium sake has seen a decrease in alcohol content overall. Ginjo et cetera has seen alcohol levels stay fairly high, likely for increased impact, but in non-premium futsuu-shu alcohol has dropped a bit on the average. I am not sure what the significance of this point is, though, nor was it elucidated upon in the government report. Milling

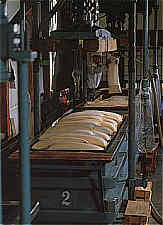

Milling This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that.

This section could be expanded to fill several books, at least. But since we do not have that luxury now, let us break it down a bit. There are three main ways of preparing the yeast starter, a few less mainstream but very valid ways, and tons of variations beyond that. Machine press

Machine press Fune (box press)

Fune (box press) Shizuku

Shizuku Pasteurization

Pasteurization Aging

Aging Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more

Fond of doing things at the last minute? Then check out the Sake Professional Course to be held in Toronto October 3, 4 and 5. Learn more  What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty.

What is it that makes a sake taste and smell the way it does? What goes into and drives the myriad flavors and aromas we enjoy in today’s sake? We could get really technical. We good go chemical if want to, but it would not likely be pretty. I. Rice = Flavor

I. Rice = Flavor Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

Koji provides enzymes that convert starch to sugar. Just how strong those enzymes are, and at what stage of the brewing process they are most active, will determine how sweet or dry the sake is. If the koji leads to lots of starch-to-sugar conversion early on, that sugar will be readily converted to alcohol leading to a dry sake. If sugar comes along later in the process when the yeast is petering out, it will remain in the sake and lead to sweetness. In truth, this too is more complicated. But therein lies the gist.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake.

Yeast is a crucial ingredients in sake. industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

industry focused more on a handful of tried and true yeast strains that have been around for about a century. And before that, everyone depended on their own in-house ambient yeast, which alone could make or break a kura’s reputation.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter.

In the movie (and play), “A Bronx Tale,” the members of a particular fraternal organization centered around their ethnicity ran a bar into which a group of members of another fraternal organization, this one centered on their preference for two-wheeled vehicles, attempted to enter. shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.”

shaking and shooting their beer and creating every kind of ruckus imaginable. At which point the head wise guy shuts the door ominously, looks around the room, and says, “Now youse can’t leave.” Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.

Of course, all this naturally leads to questions relating to how young is still young enough, or conversely stated, how old is too old? In actuality, there is no simple answer, which is why following the “younger is better, don’t mess around with aging sake at home” philosophy is best at first. But the ultimate truth is a bit higher than that.