The proponents of junmai types over added alcohol types are quick to point out how fast the junmai types are growing in production and consumption, and how fast the added-alcohol types are decreasing. And this is true enough; certainly the awareness of and preferences for junmai, junmai ginjo, and junmai daiginjo are growing steadily. Misplaced though the reasoning may be. (Did I just say that?)

The proponents of junmai types over added alcohol types are quick to point out how fast the junmai types are growing in production and consumption, and how fast the added-alcohol types are decreasing. And this is true enough; certainly the awareness of and preferences for junmai, junmai ginjo, and junmai daiginjo are growing steadily. Misplaced though the reasoning may be. (Did I just say that?)

But as always, there is bit more to the story than any one interpretation of static statistics states, alliteration fully intended.

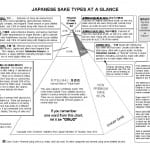

For one, futsuu-shu, the 65 percent of the market that is all made with good dollops of added alcohol for economic reasons, continues to contract fairly quickly. However, even if we limit the analysis to premium sake, tokutei meishoshu (“special designation sake”), i.e. honjozo, junmai-shu, ginjo-shu, junmai ginjo-shu, daiginjo-shu and junmai daiginjo-shu, the junmai types grow faster than the non-junmai types.

Still, there is one caveat that is conveniently ignored: that of the enigma of honjozo. Why is this? Because it is indeed premium, although (oxymoronically) at the very bottom of premium. And it is contracting faster than any other type of sake, even lowly futsuu-shu.

And this makes the numbers appear the way they do. In other words, if you look at all premium sake together, sure, junmai types are growing faster than non-junmai types. But if you take out honjozo, then the non-junmai types are growing just as fast as the junmai types.

My point is not to prop up added alcohol sake, nor to diss junmai jihadists. (Did I just say that?) But rather, the point here is to show how fast honjozo is dropping, and to consider why that might be. And lastly, to propose that it might not be as bad as it looks.

Let’s look briefly at the history of honjozo. Adding pure distilled alcohol to sake has been around since 1942, when it was enforced with good purpose, to save rice during hard times yet to let the industry survive.

When things settled down in post-war Japan, all sake continued to be br ewed with added alcohol – most often for economic reasons. But along the way, brewers learned the great things that can happen to a premium sake by adding a bit of ethyl alcohol to the mash just after fermentation – and then a bit more water later. These include coaxing out more flavor and aroma from the rice, improving shelf life, and making the final sake smoother and more well-rounded. Then, in 1968, two breweries more or less simultaneously begin brewing junmai, after which junmai types s-l-o-w-l-y gained momentum that continues today.

ewed with added alcohol – most often for economic reasons. But along the way, brewers learned the great things that can happen to a premium sake by adding a bit of ethyl alcohol to the mash just after fermentation – and then a bit more water later. These include coaxing out more flavor and aroma from the rice, improving shelf life, and making the final sake smoother and more well-rounded. Then, in 1968, two breweries more or less simultaneously begin brewing junmai, after which junmai types s-l-o-w-l-y gained momentum that continues today.

Honjozo became an industry designation in the early 70’s, and means “the original brewing method.” Which it is not; but hey, there were on a roll. What honjozo does mean is that the amount of distilled alcohol added is strictly limited, with the spirit of the rule being to show that it is added for good technical reasons like those outline above, but not just to increase yields. Also, the rice must be milled to 70 percent of its original size as well. Back in the early 70s, before junmai caught on, and when heavily-doped futsu-shu was closer to being the norm, honjozo was considered a step above in terms of both brewing philosophy and quality as well.

However, as junmai and ginjo grew in popularity, the once-lofty honjozo began to lose it significance, and so it continues today.

Why might this be? Because it is, increasingly, in this no-man’s land between cheap sake and premium sake, at least in terms of marketability. It is not futsuu-shu, but nor is it ginjo. Consumers like extremes, and honjozo is neither here nor there in the opinion of many. Sad, but true.

In other words, if someone wants to drink cheap, honjozo is too expensive and too good. If someone wants to drink premium, honjozo is perceived as the lower end of that spectrum, and summarily passed over in favor of something with the hallowed ginjo word on the label.

From the brewers’ point of view, it is pretty much the same. With jus a bit more milling of the rice, a brewer can classify it as a ginjo and benefit from all that fanfare and marketing. In fact, much honjozo was made with rice milled enough to qualify it as a ginjo anyway in the silly rice-milling wars commonplace today. So sometimes, all they really need to do is to decide to label it as a ginjo. Done.

From the brewers’ point of view, it is pretty much the same. With jus a bit more milling of the rice, a brewer can classify it as a ginjo and benefit from all that fanfare and marketing. In fact, much honjozo was made with rice milled enough to qualify it as a ginjo anyway in the silly rice-milling wars commonplace today. So sometimes, all they really need to do is to decide to label it as a ginjo. Done.

Conversely, with just a bit less effort, a brewer can sell it as a futsu-shu, and a rather good one at that, giving it a distinct advantage on the shelf when compared with really cheap sake. So the benefits of labeling a sake as a honjozo began to fade away, and continue to do so.

To be sure, there is still plenty of great honjozo left, especially tokubetsu (special) honjozo. And much of it is some of my favorite sake to drink! Not overly fruity or aromatic, still tinged with idiosyncrasies, yet clean, smooth and pleasant. Not all of it, mind you; but much of it is so.

Alas, for these reasons, the contraction of honjozo will likely continue. But in truth, the sake itself is not going anywhere, it is just being reclassified as other stuff, either a notch up or a notch down, perhaps with slight tweaking. While it is a shame to see historically significant grade of sake dry up, I myself think that the sake that remains in that classification will even more aptly represent what good honjozo can be. And I, for one, am looking forward to continuing to enjoy them. Yet I also expect them to continue to skew the statistics.

Sake Professional Course in New York City, December 7-9

The next Sake Professional Course is scheduled for New York City, December 7 to 9, 2015. The venue is smaller this time and participation is limited to 40 people. It is just about half full, or half empty, depending on your perpsective.

The next Sake Professional Course is scheduled for New York City, December 7 to 9, 2015. The venue is smaller this time and participation is limited to 40 people. It is just about half full, or half empty, depending on your perpsective.

More information is available here, and testimonials from graduates can be perused here as well. The three-day course wraps  up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

up with Sake Education Council supported testing for the Certified Sake Professional (CSP) certification. If you are interested in making a reservation, or if you have any questions not answered via the link above, by all means please feel free to contact me.

Following that, the next one is tentatively scheduled for Japan in January, and then the spring in Chicago. If you are interested, feel free to send me an email to that purport now; I will keep track of your interest!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Interested in Sake? Pick up a copy of my latest book, Sake Confidential, A Beyond-the-Basics Guide to Understanding, Tasting, Selection, and Enjoyment.

Learn more here.